Who are the profoundly gifted? And what do they need in order to thrive?

Leading experts on gifted education discussed these questions this week on the National Public Radio podcast 1A, which explores issues at the forefront of American life. The episode, titled "Rated PG: Profoundly Gifted," featured panelists Jonathan Plucker, a professor of talent development at JHU's School of Education and the university's Center for Talented Youth; Anya Kamenetz, NPR education reporter and a CTY alum; and Patricia Susan Jackson, founder and director of the Daimon Institute for the Highly Gifted.

The show's topic, the profoundly gifted, was suggested by listeners, who were invited to share their experiences. They included a mother who said she received no support from her child's school and was forced to homeschool; an aunt of a student who had dropped out of high school "because he was bored;" an African-American woman who couldn't access the resources necessary to develop her abilities; and a man who described his own experience of being labeled gifted as "paralyzing."

One common stereotype surrounding academically talented kids is that they can take care of their own intellectual needs—an assumption that can be damaging to the individual and to society, Plucker said.

Plucker, who is president-elect of the National Association for Gifted Children, used the example of a third grader starting the school year already knowing the material that will be taught that year, and for the next several years. When the needs of these types of students are not addressed, "research tells us not much happens and these kids just sit there bored for years," Plucker said.

So, once a student is identified as gifted, how can families make the most of their academic abilities? Plucker said any form of academic acceleration helps.

"Finding ways to make sure the student's curriculum and instruction is closely matching the speed at which they can learn is extremely important," he said.

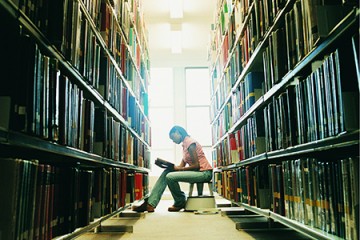

Opportunities to be around like-minded peers is also critical. Plucker highlighted programs such as CTY Summer Programs—in which students spend three weeks studying one topic—as one way to achieve this sense of community.

Kamenetz, who studied archaeology at CTY when she was 13, said the experience was valuable for her academic and social development. She relished the excitement of participating in a real archaeological dig while being around other students who were fascinated by science, politics, and history.

"CTY was a huge program for me when I was a young teen, and being on a college campus made me realize there was a reason to keep going in high school and eventually be with peers," she said.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged education, center for talented youth