How do you prepare to move the first spacecraft to touch the sun? The same way you would move anything else: carefully wrap it, pack it, rent a truck, and perform a nitrogen purge.

Last month, the Parker Solar Probe spacecraft traveled from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, where it was designed and built, to NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It's a short drive, but it took significant preparation.

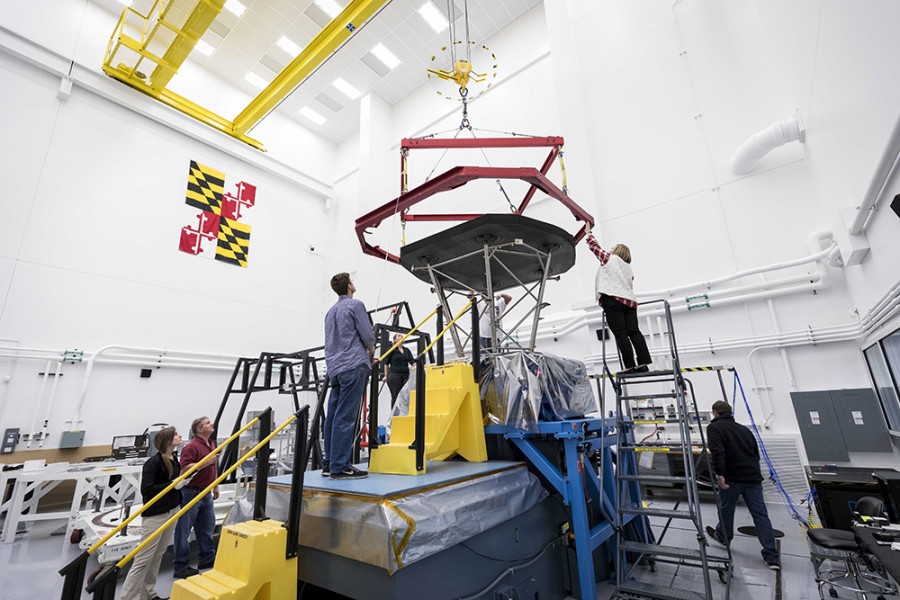

Image caption: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, shown in protective bagging to prevent contamination, is mounted on a rotating pedestal

Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Ed Whitman

First, the spacecraft was wrapped in a special protective layer to prevent dust or dirt from reaching the probe. Then it was bolted to a specially designed pedestal that carefully tilted the probe onto its side to fit it inside a shipping container. If kept upright, the probe would have been too tall to pass under highway bridges during transport.

Once boxed and loaded onto a truck bed, the scientists performed a nitrogen purge, slowly sucking air and moisture out of the container and replacing it with ultra-dry nitrogen with an extremely low dew point. A nitrogen purge is a common practice among military and commercial aerospace projects to prevent corrosive moisture and condensation from reaching sensitive electronics.

Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Ed Whitman

The move, accompanied by a state police escort, took place at 4 a.m.—to avoid traffic, of course.

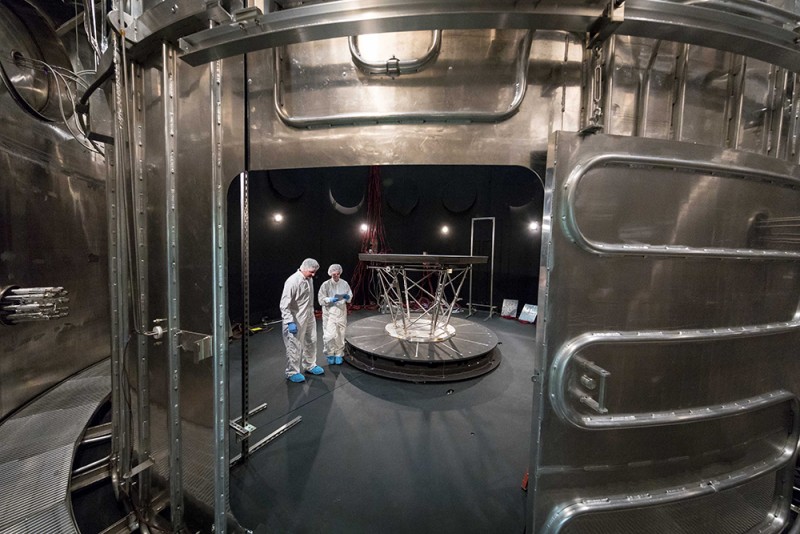

Image caption: No, it's not a still from the movie E.T., it's members of the testing team preparing the Parker Solar Probe for environmental testing in the Acoustic Test Chamber at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Ed Whitman

At Goddard, the Parker Solar Probe has undergone extensive testing and simulations to ensure it's ready for its historic mission next year (launch is scheduled for between July 31 and Aug. 19).

It underwent an acoustic test, which subjected the probe to sound forces like those generated during a rocket launch. Goddard's Acoustic Test Chamber is a 42-foot-tall chamber that uses 6-foot-tall speakers that can reach 150 decibels to simulate the extreme noise of the Delta IV Heavy, the highest-capacity rocket currently in operation and the vehicle that will carry the probe into space.

Video credit: Applied Physics Lab

The spacecraft's specially designed Thermal Protection System, or TPS, has also gone through thorough testing. The heat shield, developed by scientists at APL and the Whiting School of Engineering, is made of carbon-carbon composite material to protect the probe from the intense heat of the sun's atmosphere, which can reach temperatures of almost 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. As the spacecraft hurtles through the hot solar atmosphere and back out into outer space, the TPS will keep the instruments on the spacecraft at approximately room temperature.

Image caption: The probe's Thermal Protection System is lowered into the Thermal Vacuum Chamber at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in preparation for environmental testing

Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL / Ed Whitman

The heat shield was tested in Goddard's Thermal Vacuum Chamber, which simulated the harsh conditions that it will endure during the mission.

During its mission, the Parker Solar Probe will use seven Venus flybys over the course of nearly seven years to gradually shrink its orbit around the sun, coming as close as 3.7 million miles—about eight times closer to the sun than any spacecraft has come before. Upon its closest orbit, the Parker Solar Probe will be traveling at about 450,000 miles per hour. That's fast enough to get from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., in one second.

The solar probe, named for Eugene Parker, the astrophysicist who predicted the existence of the solar wind in 1958, is a "true mission of exploration," the scientists write on the mission homepage. "Still, as with any great mission of discovery, Parker Solar Probe is likely to generate more questions than it answers."

Posted in Science+Technology