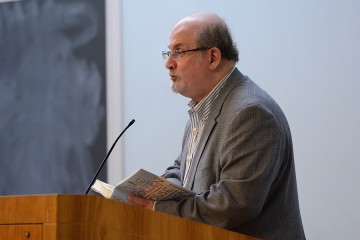

In a talk last night on the Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus, author Teju Cole declined to define his work or characterize it by a particular literary technique.

He did, however, share his thoughts on endings.

"I would never use a solution for an ending," he said.

Maybe that's why Cole, an award-winning author and photography critic for New York Times Magazine, felt comfortable reading from the endings of two of his books, Open City and the forthcoming Blind Spot during his talk as part of Johns Hopkins President's Reading Series: Neither finale reveals narrative solutions, instead layering image upon image, thought upon thought, before drifting away like a boat on water. Like the final trembling notes of a symphony.

Silhouetted against a backdrop of his own photos, Cole read a series of essays—or maybe they're prose poems—from Blind Spot, which is inspired by his experience in 2011 with big blind spot syndrome, a condition caused by damage to the blood vessels in his eye.

The book transcends narrative writing styles, drawing from his experience critiquing photographs in an exploration of what people miss when they view the world.

The essays were based on a trip Cole took around the world. In one essay, he describes the day he came across a pair of boys who spoke in unison while walking a path in a hilltop vineyard, with a lake of water sprawling below. He pairs it with a photo from that trip of a blue net, the very color of the water below, captured mid-billow in an arc over lakeside cottages. In another essay, he explores the concept of pressure exerted on the human body, pairing it with a photo taken in Brooklyn of an orange plastic Jersey barrier, knocked over on its side atop a mound of gravel.

If the images chosen for Blind Spot seem dull, it's because Cole is making a deliberate choice about how he portrays tension.

"When I take pictures of chairs that I see on a street corner, it comes from a nonreligious but deeply mystical sensibility that says these chairs are vibrating on some level that is fascinating," he said.

Also see

Cole's collection plays with a technique of stacking multiple endings one after another, finally concluding with an edited version of a photo that appears earlier in the book. The original image depicts a boy holding onto a red railing on the banks of the Congo River. Because the photo is underexposed, the boy's face isn't visible. Cole layers the accompanying essay with religious imagery.

To end the collection, he revisits that same photo, which has been edited to adjust the exposure so that the boy's face is revealed—as are his serious, intense eyes.

It's that repetition, and that contradiction, that creates a sort of "double vision" for the boy. Seeing outward, and seeing inward.

"If you want to do photography as an art, you have to think about how you evade some of the ease of this art form in order to arrive at something that pierces," he said. "That is what is intriguing, and difficult, and—ultimately—satisfying."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged literature, photography, art