With some unusual carry-on luggage and an anxious welcome committee awaiting his arrival, Ethan Leder took off from the tarmac at Dulles International Airport in the early morning of Tuesday, Oct. 3, destined for hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico.

His mission: to personally deliver as many medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and emergency items as his jet could carry.

Rural areas of Puerto Rico have faced significant, devastating delays of aid following Hurricane Maria, which made landfall Sept. 20 as one of the strongest storms to hit the island in the past century.

Image caption: Ethan Leder (top left) helps unload a plane filled with supplies

Image credit: Courtesy of Ethan Leder

Leder's plan began as a late-night epiphany while watching an evening news segment about the blockades and bureaucratic red tape preventing supplies from leaving the ports in San Juan, Puerto Rico's capital. Leder—a 1984 Johns Hopkins University graduate, a member of JHU's board of trustees since 2011, and co-founder of Precision Medicine Group—says he was disturbed by the disorganization he saw.

"I was getting very frustrated listening to these reports, and I just couldn't understand how the large relief organizations and our federal government couldn't do more," he says.

That night—Thursday, Sept. 28—a friend connected him to a Puerto Rican-born D.C. businessman, José Ortiz. Together, they discussed what could be done to help the people on the island. By Saturday, they were raiding wholesalers like Costco for infant formula, pain and anti-diarrheal medicines, insect repellents, and protein bars. They stopped by the sports outfitter REI to meet with the general manager and purchase as many water purification systems and solar LED lanterns as the store had in stock.

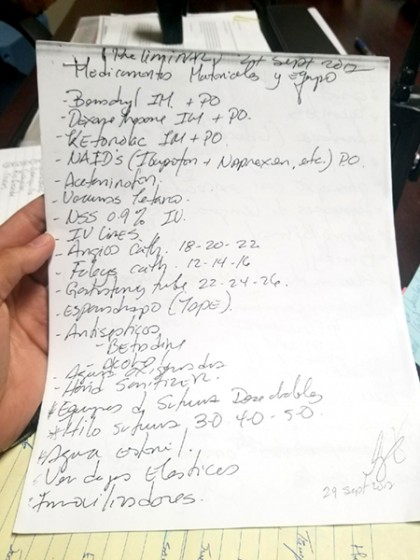

Ortiz had put Leder in touch with a city administrator and a head doctor from Aguada, Puerto Rico, a town of less than 50,000 people on the island's west coast. The doctor sent Leder a seven-page, handwritten list of the supplies the town needed.

"So then I went to work on my friends and colleagues," Leder jokes.

By Monday, and with the help of members of Precision Medicine Group—including Hopkins alum Kevin Roach—Leder had contacted executives from regional health care providers including Suburban Hospital (which is part of the Johns Hopkins Health System), the MedStar Health System, and Superior Biologics. They provided medicines to care for chronic conditions, such as insulin for regulating diabetes. They also provided what Leder calls "battlefield" supplies—antibiotics, drugs, tools, and first aid items that are the most critical and in-demand during disasters and emergencies.

Image caption: Through Ortiz, Leder was able to connect with a doctor in Aguada, Puerto Rico, who supplied a handwritten list of the supplies that were most needed

Image credit: Courtesy of Ethan Leder

"When there's no running water or electricity, nothing can be sterilized," he says. "So the doctors had to have disposable medical and surgical supplies in order to treat their patients."

By 6 a.m. Tuesday morning, they were ready for takeoff.

The group touched down in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, where the island's second largest airport is located, after a quick stopover in Fort Lauderdale to load additional supplies and switch to a larger plane. Then they made their way to nearby Aguada and the makeshift clinic that had been set up in one of the town's churches.

"Their hospital had been wiped out—it was unusable," Leder says. "When we arrived at the clinic, they brought us into this big room full of people waiting to be treated. There were doctors and nurses who looked exhausted. When we went to the front of the room, I saw two elementary school-sized desks, each with a tray of supplies on them—and that's all they had."

When the head doctor saw the van of supplies waiting outside, he broke down and wept, says Leder.

Also see

"He told me, 'You don't understand, we've been working with nothing,'" he says.

On that first trip, Leder and Ortiz brought more than 1,500 pounds of supplies to Aguada. On their return flight back to the mainland, they brought with them a mother and her three young children who had family in Jacksonville, and a dialysis patient who had been forced by the drug and power shortage to ration her treatment.

When Leder returned home, he says he had received at least 100 phone calls and emails from colleagues, friends, former business partners, and medical professionals asking how they could contribute to his mission. So he began planning a second trip.

On Oct. 10, Leder and Ortiz were joined by Angelique Sina, co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit Friends of Puerto Rico, who had connections to other west coast mayors and city administrators. Again they landed in Aguadilla, this time meeting on the tarmac representatives from four neighboring municipalities: Isabela, Las Marías, Maricao, and Moca. They divvied up more than 2,500 pounds of supplies.

Leder says the experience opened his eyes to the demands and the urgency of disaster relief.

"In natural disasters, you have to first stabilize the situation by any means necessary and as fast as possible," he says. "Then, you evaluate and set up the infrastructure that will let you sustain your efforts over the long haul. In this instance [of Puerto Rico], it seems that the larger relief efforts have not deployed rapidly enough to address the consequences of Hurricane Maria. We can—and must—do better."

He adds that it was personally fulfilling to be able to provide the aid that he could. The experience illustrates, he says, the ability of individuals and small groups to make a difference in the lives of others.

"It was an honor to be able to do this," Leder says. "But it's really important that I say this: I'm not superhuman, I'm just a person. I have some resources, and I was willing to invest the resources and call on my friends, who were incredibly generous and more than willing to provide key supplies. Because we were able to act with very practical and specific goals and without overburdening the mission with restrictions, we were able to make quite a bit of progress quickly. It tells me that if we could amplify these ingredients, particularly in the early days of an emergency, then we could really make a difference."

Posted in Health, University News

Tagged disaster response, natural disasters, hurricanes, board of trustees