On the cusp of last year's presidential election, many working-class voters who were once staunch Democrats had gone independent, opening the door for a non-traditional Republican candidate, a new Johns Hopkins University study concludes.

The report, which documents a decades-long shift away from traditional party affiliation within the working class, is believed to be the first assessment of how social class affected political identity in the run up to the 2016 presidential election. It will appear in this month's issue of the journal Sociological Science.

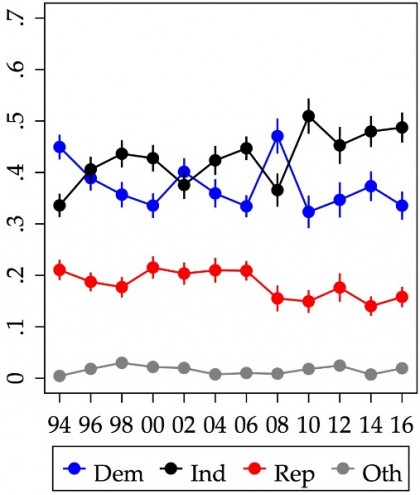

Image caption: A graphic of working-class party identification from 1994-2016 shows that most identify as independents.

"A substantial proportion of eligible voters within the working class turned away from solid identification with either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party during the Obama presidency," wrote lead author Stephen L. Morgan, a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Education. "Even before the 2016 election cycle commenced, conditions were uncharacteristically propitious for a Republican candidate who could appeal to prospective voters in the working class, especially those who had not voted in recent presidential elections but could be mobilized to vote."

Morgan and graduate student Jiwon Lee studied data from the 1994 through 2016 editions of the General Social Survey, to model how party identification has evolved over the past 24 years.

They focused on more than 30,000 eligible voters. The survey asks respondents which political party they identify with, as well as questions about their occupation and education, which allowed the researchers to determine how working-class voters aligned themselves politically over time.

"We found substantial change in party identification across the presidencies of Bill Clinton, George Bush and Barack Obama, particularly during Obama's tenure," Morgan said. "Many eligible working-class voters were becoming less attached to the Democratic Party, but their loyalties weren't shifting to the Republican Party."

Many of these voters—lower-paid, lower-skilled workers often in blue-collar jobs—had begun to consider themselves independent, Morgan found.

This softening of party identification opened the door for a candidate like Donald Trump, who could appeal to former Democrats who were uncomfortable with the Republican Party establishment.

The survey didn't explore why voters who changed party affiliation did so, but Morgan suspects a number of causes: a slow economic recovery after the recession, a failure by those in office to prosecute the individuals responsible for the collapse of financial institutions, and the continuing erosion of real wages for semi-skilled and unskilled workers.

Morgan estimates that between 6 and 10 percent of working-class voters shifted allegiances, not enough for the Democratic Party to entirely lose its overall working-class advantage.

Meanwhile, Morgan found certain other Democrats became even more loyal to the party: white-collar professionals and other higher-paid workers. With their relative affluence and stability, these Democrats were less affected by the recession and more inclined to support what have become bread and butter issues for the Democratic Party—social matters like climate change and same-sex marriage.

A silver lining for Democrats, Morgan said, is that some of these lost working-class voters didn't support a traditional Republican, but someone who appealed to their economic interests.

"That these positions were also nativist and xenophobic is undeniable, and so the lead lining of those same clouds for the polity as a whole is that the particular nature of the Republican candidate's appeals to working-class economic interests were not deemed sufficiently noxious to prevent electoral success," Morgan wrote. "Rejection of the civil rights agenda, however defined, appears fashionable again."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged sociology, politics, stephen morgan, election 2016, donald trump