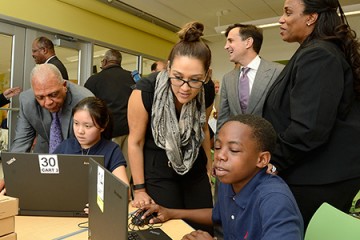

Johns Hopkins University's Louis Whitcomb, a professor of mechanical engineering, threw down a challenge to sixth-graders at Baltimore's Barclay Elementary/Middle School: design a claw that could allow one of his underwater robots to grab submerged objects.

Darrius Crawford responded with what he called "The Hammerhead" and presented it to Whitcomb on Thursday.

Darrius built his Hammerhead claw from nothing more than corrugated cardboard, straws, string, brass fasteners, tape, paper clips, and rubber bands. He wanted it to be able to grab and scoop with ease, and his creation's standout feature—a wide, flat, hammer-like front-piece—did just that.

"We wanted to come in here and show you all that we could do something," Darrius told Whitcomb.

A partnership between Johns Hopkins University and Baltimore City Public Schools, announced in 2015, allowed Barclay to become the city's first designated pre-K through eighth-grade school dedicated to giving students a foundation in engineering and computer science. As part of the partnership, the Whiting School of Engineering's Center for Educational Outreach offers an annual design challenge at the school. This is the first time students have been challenged to create something that functions underwater.

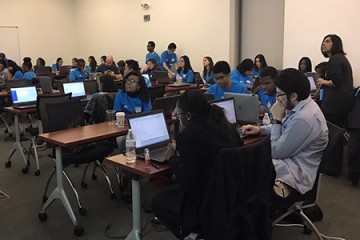

The sixth-graders, split into teams of two or three, worked on their designs for about two weeks, getting guidance from Johns Hopkins engineering undergraduate students who signed up for the program through a one-credit Intersession course.

The point of the challenge is to offer the kids a realistic engineering task and the chance to interact with young people—not that much older than they are—who are on the path to becoming engineers, said Margaret Hart, the Center for Educational Outreach's middle school STEM program manager. Meanwhile, the undergraduates learn how to communicate complex scientific material to non-technical people.

On Thursday, the students presented their designs to Whitcomb and a panel of other judges—a few of his graduate students.

Brionna Vines impressed the panel with her two-jointed claw arm. "How did you think of that?" Whitcomb asked her.

"We didn't want something everyone else had," said Brionna, who later called her design "tight and right."

Awoe Mauna-Woanya, a freshman majoring in civil engineering who worked with Darrius, said working like this with young people is important to him because when he was a boy, he was inspired by a similar program.

"It gave me something to look up to," he said, "and a goal to push for."

As the students presented their claws, Whitcomb told several of them to consider going to the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute for high school, because of its curriculum focusing on the sciences.

"We want to encourage students to consider science and engineering," he said. "We need to convince kids that they can actually do this stuff."

Posted in Science+Technology, University News, Student Life, Community

Tagged mechanical engineering, community, intersession