The unusual darkness of Mercury's surface has always been a big question mark for scientists. But a new study reveals that the darkening agent is likely carbon—from Mercury's original, 4.6-billion-year-old crust.

Researchers from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory believe the carbon probably originates deep below the surface of the solar system's innermost planet, within an ancient, graphite-rich crust that was later buried by volcanic material.

Their study, led by APL research scientist Patrick Peplowski, was published recently in Nature Geoscience.

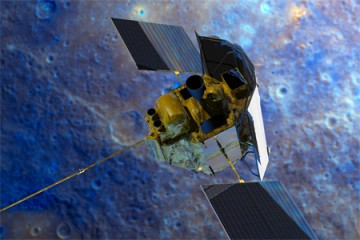

The scientists came to their conclusions with data collected from the NASA spacecraft Messenger last April as it circled within kilometers of Mercury's surface during the final phase of its four-year geological survey of the planet.

A process of elimination has singled out carbon as the most likely darkening agent for Mercury's surface. More common darkening elements like iron or titanium—which contribute to the darkness of the moon, for example—aren't abundant enough on Mercury to explain the effect there. About a year ago, scientists started to zero in on carbon—in the form of graphite—but were skeptical of the abnormally high concentrations of the mineral that would be required to produce the darkening effect.

The low-altitude Messenger data narrowed the pool further, determining that the darkening agent must be an element that's inefficient at absorbing neutrons. Carbon is the only mineral that matches that condition that could account for Mercury's darkness.

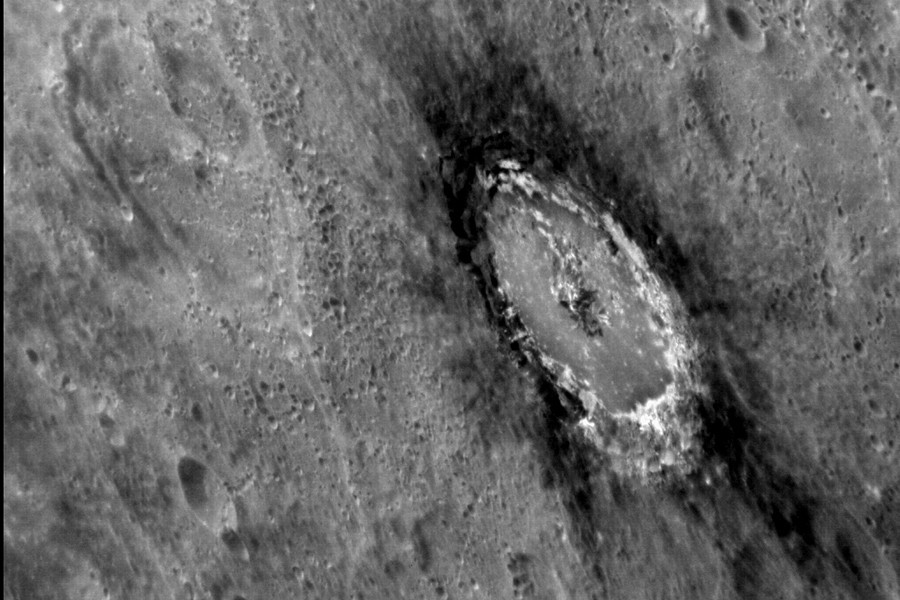

The scientists believe the carbon is concentrated in Mercury's low-reflectance material, which has its sources deep within the planet's crust. Deposits of that material are only brought to the surface by large impact craters, according to study co-author Rachel Klima, an APL planetary geologist.

Like the moon and other inner planets, Mercury probably had a magma ocean when it was very young, Klima said. As this ocean cooled, buoyant carbon graphite would have accumulated as the original crust of Mercury. The low-reflectance material the scientists are now observing likely contains remnants of this crust—"the remains of Mercury's original, 4.6-billion-year-old surface," Klima says.

The recent findings could eventually help scientists understand more about Mercury's original crust and the volatile material from which the planet formed. Further study of the low-reflectance material is necessary to find out what minerals may be present beyond carbon, the APL scientists say.

"If we've really identified the remains of Mercury's original crust, then understanding its properties provides a means for understanding Mercury's earliest history," Peplowski says.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, nasa, messenger, mercury