Mission controllers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory confirmed Thursday afternoon that NASA's Messenger spacecraft had crashed into the surface of Mercury, as predicted, at 3:26 p.m. The team was able to confirm the end of operations just a few minutes later, at 3:40 p.m., when no signal was detected by the Deep Space Network station in Goldstone, California, at the time the spacecraft would have emerged from behind the planet had it not impacted the surface.

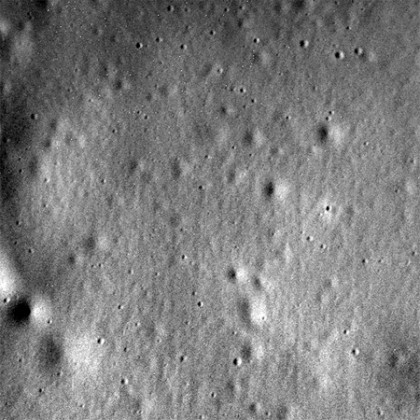

Image caption: The final image sent by NASA's Messenger spacecraft before it crashed into Mercury's surface

Image credit: NASA/JHU Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

"Today we bid a fond farewell to one of the most resilient and accomplished spacecraft ever to have explored our neighboring planets," said Sean Solomon, Messenger's principal investigator and director of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

"Our craft set a record for planetary flybys, spent more than four years in orbit about the planet closest to the sun, and survived both punishing heat and extreme doses of radiation. Among its other achievements, Messenger determined Mercury's surface composition, revealed its geological history, discovered that its internal magnetic field is offset from the planet's center, taught us about Mercury's unusual internal structure, followed the chemical inventory of its exosphere with season and time of day, discovered novel aspects of its extraordinarily active magnetosphere, and verified that its polar deposits are dominantly water ice. A resourceful and committed team of engineers, mission operators, scientists, and managers can be extremely proud that the Messenger mission has surpassed all expectations and delivered a stunningly long list of discoveries that have changed our views not only of one of Earth's sibling planets but of the entire inner solar system."

Messenger was launched on August 3, 2004, and it began orbiting Mercury on March 18, 2011. The spacecraft completed its primary science objectives by March 2012. Because Messenger's initial discoveries raised important new questions and the payload remained healthy, the mission was extended twice, allowing the spacecraft to make observations from extraordinarily low altitudes and capture images and information about the planet in unprecedented detail.

Last month, during a final short extension of the mission referred to as XM2, the team embarked on a hover campaign that allowed the spacecraft at its closest approach to operate within a narrow band of altitudes, five to 35 kilometers above the planet's surface. On April 28, the team successfully executed the last of seven orbit-correction maneuvers, which kept Messenger aloft for the additional month, sufficiently long enough for the spacecraft's instruments to collect critical information that could shed light on Mercury's crustal magnetic anomalies and ice-filled polar craters, among other features.

With no way to increase its altitude, Messenger was finally unable to resist the perturbations to its orbit by the sun's gravitational pull, and it slammed into Mercury's surface at around 8,750 miles per hour, creating a new crater up to 52 feet wide. Before impact, Messenger's mission design team predicted that the spacecraft would pass several miles over the lava-filled Shakespeare impact basin before striking an unnamed ridge near 54.5°N latitude and 210.1°E longitude.

"Going out with a bang as it impacts the surface of Mercury, we are celebrating Messenger as more than a successful mission," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "The Messenger mission will continue to provide scientists with a bonanza of new results as we begin the next phase of this mission—analyzing the exciting data already in the archives, and unraveling the mysteries of Mercury."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, nasa, space, messenger