Johns Hopkins University physicists today are celebrating the announcement that Francois Englert of the Université Libre de Bruxelles and the University of Edinburgh's Peter Higgs have been named co-winners of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics for their independent predictions 50 years of the existence of the Higgs boson, the so-called "God particle."

Hopkins physicists were members of one of two collaborations conducting the Higgs hunt at the Large Hadron Collider, the world's largest particle accelerator, located in Geneva, Switzerland, at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Andrei Gritsan, an experimental physicist and associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins, was a member of the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment collaboration and co-leader of a group that investigated one of the most promising avenues to revealing how the Higgs particle could be found and studied.

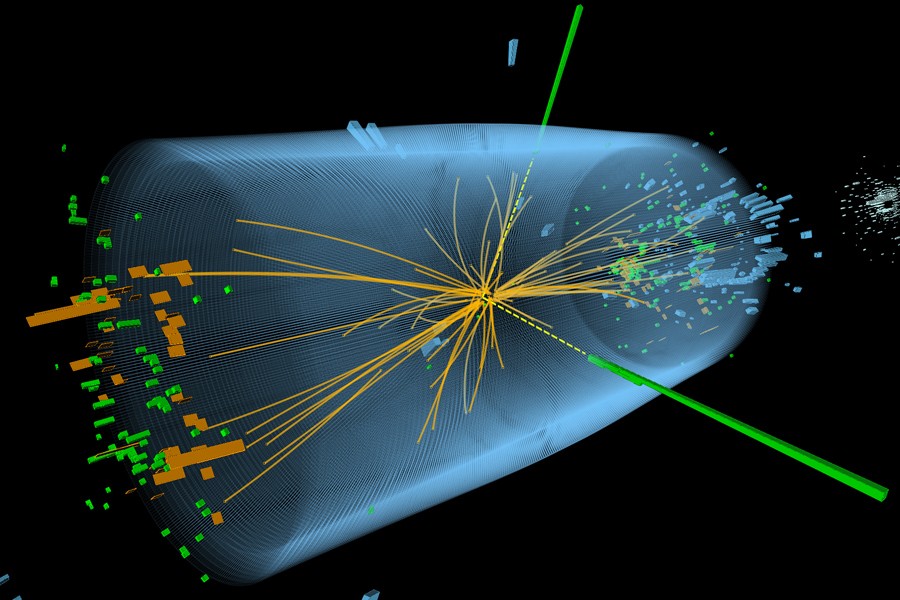

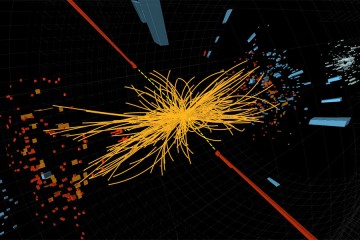

"The challenge was to actually 'see' the Higgs bosons once they are created," said Gritsan, who worked alongside more than 2,000 other scientists and researchers on the project. "One aspect is to make the scientific instrument, the CMS detector in our case, as precise as possible. With my team at Hopkins and leading a group of several experts, I developed the methods to precisely focus the key system of the detector, the silicon tracking system. Also, with my team, we developed the methods to extract maximum information from the relative angles and momenta of Higgs boson traces. This gave us confidence at the time of discovery and later to call what we see a Higgs boson."

In reviewing the data from the collider, researchers knew a graph with a bump in it would indicate strong evidence that it had produced the elusive Higgs boson. The Higgs boson, first proposed in the 1960s, was needed to fill in the largest gap in the Standard Model, the leading theory in fundamental particle physics. Its existence would signify the existence of a field that permeates all space and imbues the matter in the universe with mass.

The particle was first detected in July 2012, and its discovery was confirmed in March 2013.

"It all changed in an instant," Gritsan said. "It was an emotional moment and it left no doubt that we had something big."

Also playing parts in this historic discovery were four other Johns Hopkins physics and astronomy professors: Morris Swartz, whose work focuses on the development of radiation-hard silicon pixel sensors; Petar Maksimovic, who works on signatures of the physics beyond the standard model of elementary particles; Bruce Barnett, who was a member of the team which discovered a top quark at Tevatron; and Barry Blumenfeld, the leader of a widely-distributed system to provide database information to remote computer nodes.

"This was a truly amazing team work where people with different backgrounds, nationalities, and ages came together with a common goal and nothing else mattered," Gritsan said. "There were no country boundaries when it came to sharing of ideas, technology, computers, or the data."

David Kaplan, also a theoretical physicist at Hopkins, was so fascinated by the Large Hadron Collider and the work of CMS that he produced a documentary on the subject. Particle Fever currently is making its way through the film festival circuit and receiving positive reviews from industry insiders. The film highlights the work of six devoted scientists as they attempt to recreate conditions that existed just moments after the Big Bang. Particle Fever recently screened at the New York Film Festival and had its North American debut at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado.

Also see: Chasing the Higgs boson (The New York Times, March 5, 2013)

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged nobel prize, physics, particle physics, higgs particle