Lonni Sue Johnson's quirky, clever, colorful illustrations appeared in such prominent publications as The New Yorker and The New York Times before an attack of viral encephalitis in 2007 left the artist (who also was a pilot and an organic dairy farmer) with severe, memory-impairing brain damage.

The virus attacked both sides of Johnson's brain, ravaging the hippocampus, a structure crucial for forming and storing new memories. The illness also damaged other portions of her temporal lobe that scientists think may also be important for memory and other abilities, such as language and perception. As a result, Johnson, who is in her early sixties, not only could not remember much detail about her pre-illness life, but also seemed unable to remember what happened just minutes earlier.

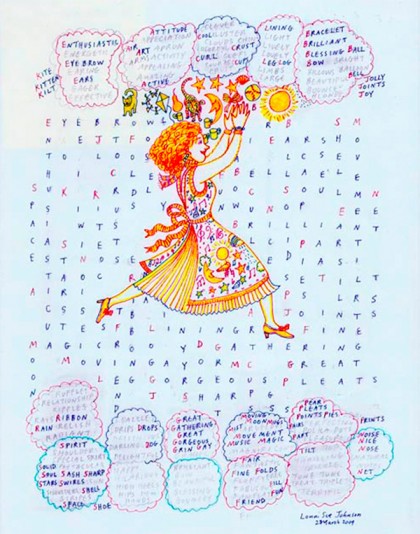

Enter the power of art. Under the guidance of her mother (also a professional artist), Johnson began putting pencil to paper and created a voluminous collection of "recovery art" that her family collected. Johns Hopkins researchers are now studying these—and the artist herself—in an effort to unlock the secrets of the brain and creativity. Some of these images (produced both before and after the attack of encephalitis) will be on display at the Walters Art Museum September 17 through December 11 in a unique exhibition called "Puzzles of the Brain: An Artist's Journey through Amnesia."

A partnership between the Johns Hopkins University's Department of Cognitive Science and the Walters, and supported by Johns Hopkins' Brain Science Institute and the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, the exhibition features more than three dozen drawings exploring the impact of severe brain damage on the life and creativity of this artist. Viewed chronologically, the collection tells an inspiring story of how one artist is moving forward in the aftermath of a devastating illness. The compilation also poses fascinating scientific questions about the nature of perception, cognition, imagination, creativity and the brain, says cognitive scientist Barbara Landau, Dick and Lydia Todd Professor at the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences at Johns Hopkins, and principal investigator on the study.

"Lonni Sue's case suggests an intriguing new set of research questions that can shed light on the nature of artistic creativity and how it can become derailed with brain damage and then restored thereafter," Landau said. "It also offers us the opportunity to use the science we are doing to work with a broader community—in this case, through the Walters—to promote an appreciation of the synergies between art and science."

Over the last year, Landau and her research partner, Michael McCloskey (also a professor in the Department of Cognitive Science at Johns Hopkins) have tested Johnson in a number of ways, using both standardized tests and "tailor-made" instruments that they have developed to explore more specialized areas on inquiry, such as Johnson's remaining knowledge of art and artists.

"Preliminary probing of Lonni Sue's memories before the illness has shown us that she has been severely affected by the encephalitis not only as far as events in her own life, but also for famous faces, names and places, including places she knew extremely well," said McCloskey. "We've also found that she has serious impairments when it comes to learning and remembering new words, new faces and so on."

Even so, the research team is struck by Johnson's surviving vocabulary and facility with words. Indeed, her "new" artwork is strongly word-oriented. In fact, it was a word-search puzzle book given to her by a friend that sparked a breakthrough in Johnson's recovery as an artist post-encephalitis. Johnson quickly began to make word lists of her own, which she then inserted into grids by theme or in alphabetical order. Some of the drawings are remarkably simple and others are fantastically complex.

"All in all, Lonni Sue's story is both an inspiring and intriguing one that brings up a host of questions that we hope eventually to be able to answer," McCloskey said.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged brain science, cognitive science, barbara landau, science of learning, memory