World-renowned scientist and dedicated naturalist Susan Courtney, professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, died suddenly on June 10. She was 57. Courtney served as Johns Hopkins' vice provost for faculty affairs from 2017 to 2019, and chaired the psychological and brain sciences department from 2013 to 2017.

Image caption: Susan Courtney

Courtney's research focused on working memory, attention, and cognitive control in an effort to understand the neural basis of higher cognitive function. Instrumental in unifying what is known about working memory across the field, she was especially interested in how the brain structure's evolution through aging or disease affects its function.

"You need people with this kind of vision to bridge the gap between narrower research questions to get at the bigger picture," said Thomas Hinault, a former postdoctoral fellow in Courtney's lab.

Hinault points to his two years in Courtney's lab as pivotal in the kind of mentor and researcher he has become. "She was always patient, kind, and she took the time to think about the research projects we were doing and to be as thorough and relevant as possible," said Hinault, now a research scientist at the French Institute of Health and Medical Research in Caen, France.

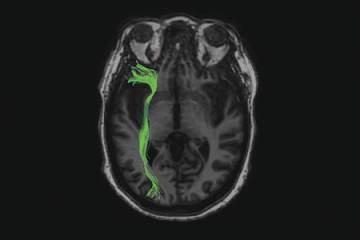

Courtney used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), cognitive testing, and computational modeling to develop an integrated understanding of the dynamic neural systems she was interested in, from the activity of single cells to behavior.

"She demonstrated the kind of leadership and dedication to her research that her colleagues and students alike found inspiring," said Christopher S. Celenza, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

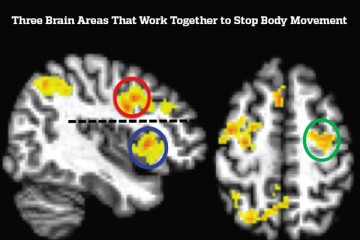

Courtney's research on how humans stop a planned movement at the last moment—such as preventing a step onto what we just realized was ice—mapped the neural basis for inhibiting movement, helping to explain what's going wrong in the brain when people fall more as they age and when people with addictions can't stop binge behavior, for example.

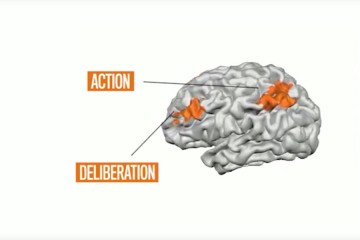

Her research showing that two different areas of the brain are responsible for the way human beings handle complex sets of "if-then" rules contributed to understanding of psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attention deficit disorder. Rules that are not part of people's everyday habits and that they therefore must actively remember—like how to adjust for a sudden change of plans—are controlled primarily through the prefrontal cortex, Courtney found.

"Susan's deep passion for understanding the relationship between brain and mind has been a continual source of enrichment for her students and colleagues," said Lisa Feigenson, professor and chair of the department. "She approached her work, and her relationships with all of her students and collaborators, with a characteristic patience and steadiness that will be deeply missed."

Courtney's colleagues note how the patience and kindness she was known for extended from the personal to the professional.

"Susan Courtney was a great person to collaborate with and I will sorely miss the weekly meetings of our research seminar," said Howard Egeth, professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. "She was, almost needless to say, very smart and knew a great deal about lots of useful topics. But equally important, she was very open-minded and was willing to consider a research topic from many different perspectives. Her collegiality went beyond research; the department will miss her wise, calm presence at our faculty meetings."

Known also for her profound curiosity about the world, Courtney was a fan of watching hummingbirds at her feeder and of exploring nature in general. The genuine care she brought to her relationships stood out.

"I am deeply grateful for Susan's gentle guidance and mentorship as my PhD adviser," said Caroline Montojo, A&S '07 (MA), '12 (PhD), who is now president and CEO of the Dana Foundation. "When I would sit in her office during our weekly meetings, I remember appreciating not only her strong scientific mind, but also the presence of many photos of [her children] Serena and Siraj on her desk and bookshelves. One of the many lessons that Susan instilled in me was the importance of cherishing an intellectual and professional pursuit, while fully embracing the emotional and spiritual richness of life and relationships."

"Susan was a committed, caring, and brilliant mentor," added Natalia Khodayari, a current graduate advisee of Courtney's. "Beyond her incredible ability to teach and research the mind and brain, Susan always strove for her students to be happy and healthy. She was far more than a beloved mentor, but a loving friend to all."

Courtney arrived at Hopkins in 1999. She held joint appointments in the School of Medicine's Department of Neuroscience and in the F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging at the Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Courtney earned a bachelor's degree in physics from Williams College in 1988, and master's and doctoral degrees in bioengineering from the University of Pennsylvania in 1990 and 1993, respectively. She did postdoctoral training at the National Institute of Mental Health's Laboratory of Brain and Cognition from 1993 to 1998.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged neuroscience, psychological and brain science, krieger school