- Name

- Jill Rosen

- jrosen@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9906

- Cell phone

- 443-547-8805

The more crime that occurs along a student's way to school, the higher the likelihood that student will be absent, Johns Hopkins University researchers found.

By modeling the most efficient routes to school for Baltimore students, researchers from the university's School of Education found those who commute through areas with double the average amount of crime are 6 percent more likely to miss school. Routes to school with even higher crime rates resulted in proportionately more absenteeism. The findings, which demonstrate yet another way urban violence affects school outcomes, appear today in the journal Sociological Science.

"Having to travel through dangerous streets is leading kids to miss school," said lead author Julia Burdick-Will, a School of Education professor who holds a joint appointment in the Department of Sociology in the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. "Not showing up for school has important academic consequences, and students who must prioritize their own personal safety over attendance have a clear disadvantage."

Chronic absenteeism has been linked to lower achievement, student disengagement, and increased risk of dropping out. Researchers including Burdick-Will have shown that students exposed to violent crime have lower test scores and lower graduation rates.

Meanwhile families, especially those living in violent and disadvantaged neighborhoods, are increasingly choosing to send their children to schools in different parts of town. But getting to these schools is often difficult. Many districts have cut back on traditional school busses and students must use public transportation. This means just showing up to school every day can mean long and difficult journeys through potentially dangerous streets, Burdick-Will says.

This is the first time anyone has attempted to gauge how neighborhood violence might influence school attendance.

Researchers first determined the quickest, most efficient route to school using public transportation for 4,200 first-time 9th-graders in Baltimore City public high schools. Then they linked those streets with crime data from the Baltimore Police Department.

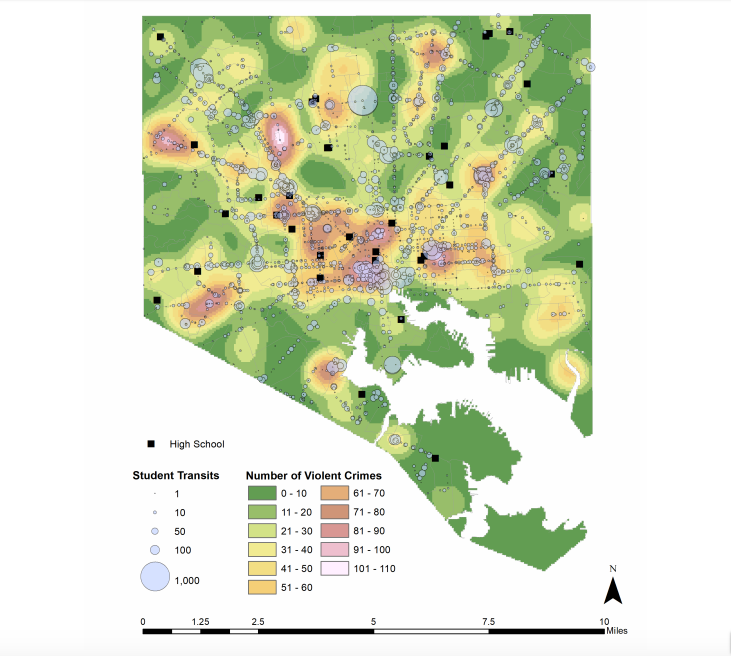

Image caption: The above map of Baltimore shows transit stops by student volume overlaying a heat map of the number of violent crimes in the area.

Image credit: Julia Burdick-Will

The team found that students whose best route required walking or waiting for a bus in areas with higher violent crime rates had higher rates of absenteeism throughout the year. And violence wasn't limited to certain parts of town—these hotspots were essentially located all over the city.

The average student went to school in a neighborhood where 87 violent crimes were reported during the academic year, but lived in a neighborhood where 95 violent crimes happened during the same time. The average student also passed streets on public transit where 41 violent crimes happened and passed streets on foot where there were 27 such crimes.

The relationship between exposure to violence during the commute to school and absenteeism provides important insights into the ways urban violence links to low achievement and high school dropout, the researchers conclude. Not only are students stressed and traumatized by violence in their communities, they say—they're missing school because of it.

"What if the closest bus stop isn't safe and you need a ride to a farther stop? Then what if that ride falls through? Do you risk it or walk really far, or do you just not go to school?" Burdick-Will says. "Missing an extra day of school a year doesn't sound like a lot but these things add up."

Co-authors for the study include the School of Education's Marc Stein, an associate professor; and Jeffrey Grigg, an assistant professor.

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged education, sociology, urban violence, baltimore city public schools, absenteeism