In a clinical trial of the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab, half of 25 patients with a rare type of virus-linked skin cancer experienced substantial tumor shrinkage lasting nearly three times as long, on average, than with conventional chemotherapy. Several patients had no remaining evidence of the disease, known as Merkel cell carcinoma.

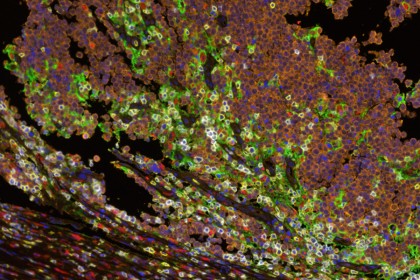

Image caption: Multispectral immunofluorescence showing the interface between Merkel cell tumor cells (orange) and host immune cells (yellow marks CD8+ lymphocytes, red marks CD68+ macrophages). Cell-surface PD-L1 expression (green) is observed on macrophages, lymphocytes and tumor cells, adjacent to PD-1 expression (white) on lymphocytes.

Image credit: Janis Taube, Johns Hopkins

Results of the study are published online today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Scientists at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, who led the study, say the results could be a harbinger of how some patients with virus-associated cancers—which account for more than 20 percent of cancers worldwide—might respond to certain drugs called immune checkpoint blockers or inhibitors.

"If additional studies with more patients confirm our findings, we will have strong reason to believe that many cancers with virus-linked proteins could be valid targets for immune checkpoint blockade," says Suzanne Topalian, professor of surgery and oncology and associate director of the Bloomberg-Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Merkel cell carcinoma is diagnosed in fewer than 2,000 people annually in the United States. It tends to occur in older people and those who have suppressed immune systems, says William Sharfman, associate professor of oncology and dermatology and director of cutaneous oncology at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. Approximately 80 percent of Merkel cell carcinomas are caused by a virus called Merkel cell polyomavirus. The rest are caused by exposure to ultraviolet light and other unknown factors.

Investigators at eight medical centers across the United States examined 26 patients with metastatic or recurrent Merkel cell carcinoma who had not previously received any systemic therapies for advanced disease. All of the patients had received standard therapy with surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Each of the patients received pembrolizumab intravenously every three weeks and received imaging scans every two to three months while receiving the drug. The researchers identified patients who responded to the drug according to standard oncology benchmarks—that is, patients who showed 30 percent or more shrinkage in measured tumors and no new lesions after two sets of imaging scans at least one month apart.

In the study, 14 of 25 patients (56 percent) whose scans were evaluated responded to the drug. Four of those patients had a complete response, with no remaining radiologic evidence of cancer. Twelve of the 14 continued to respond to the drug after a median follow-up time of 33 weeks.

According to Evan Lipson, assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, about half of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma typically respond to various chemotherapy combinations, but their cancers recur after an average of three months.

"Compared with traditional chemotherapy, about the same percentage of patients responded to pembrolizumab in this study, but these patients' responses were longer lasting," he says.

Pembrolizumab works to block a protein called PD-1 found on the surface of immune system T cells. The blockade cuts off a molecular "handshake" between the T cells and cancer cells. When the handshake doesn't happen, T cells recognize the cancer cells as foreign and mark them for destruction.

"We're learning that tumor architecture is important to understanding the immune response in cancer," says Topalian.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged cancer, johns hopkins kimmel cancer center, immunotherapy