Comics artist Ben Katchor, who returns to Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus next week for the first time since 1999, has thought about and depicted cities in his work for decades.

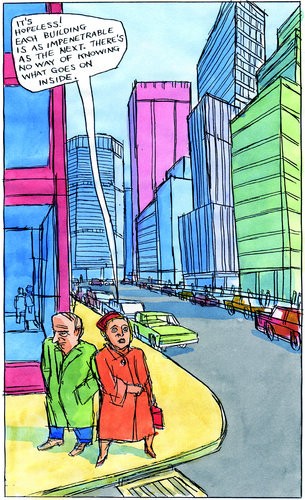

His comic strip "Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer"—which debuted in 1988 in the New York Press, the weekly formed by Hopkins alumnus Russ Smith that same year—documented its titular photographer's sometimes surreal perambulations around a city in decline.

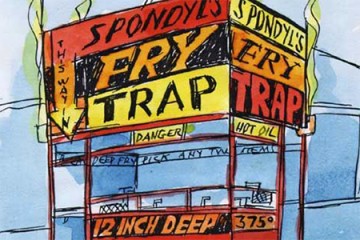

The more recent Hand-Drying in America and Other Stories, Katchor's 2013 collection of his long-running comic for the architecture magazine Metropolis, offers one man's highly detailed, personally nuanced, and gorgeously rendered experience of living in a modern urban environment.

Image credit: Ben Katchor

Katchor has "crafted his own special genre of comic strips dealing with the history and architecture of an imaginary New York," Canadian critic and essayist Jeet Heer wrote of Katchor's Metropolis contributions, "created with the goal of helping us appreciate the real city whose sheer physical and informational density defies human comprehension."

Katchor, a 2000 MacArthur Fellow who currently works as an associate professor at the Parsons School of Design at The New School in New York, says he stopped doing weekly strips when economic difficulties befell alternative weekly presses. But a weekly strip in black-and-white newsprint, a full-page color in a magazine, a graphic novel—these are all mere platforms for the narrative ideas he wants to explore, he says.

"These are stories, and a story is a pretty malleable thing," Katchor said by phone recently. "You can make it into an hour-long piece of theater or you can make it into an eight-panel comic strip. The forms have their limitations. These were venues that I had, and if all I had was a half page, I worked toward these limitations."

Katchor visits Johns Hopkins on Monday for an event co-sponsored by the Center for Visual Arts and the Homewood Arts Programs. The Hub caught up with Katchor to talk about cities, how they change, and what art can say about them.

A number of your comics take place in urban environments, which continue to undergo dramatic change. One of the many things I like about the Metropolis comic is that it reminds us that being a city dweller means living in a present where the past and future overlap, that cities relate to how we interact with them and each other. How has living in and with a changing city like New York informed your work?

The city I live in has become more like a shopping mall, with chain stores taking a over a lot of the street life, and I reflect that in my strips. If you look at the last few years of Metropolis, a lot of it has to do with that—these walk-in medical stores and various chain stores selling things of dubious value. That's a whole subject to talk about. Why is that? If you want to homogenize commodities around the world, is it necessarily a bad thing or is it just a matter of how it's done and who's running those things? I mean, I have nothing against state-controlled coffee shops, but I don't know that Starbuck's is the company I want to trust with that.

What role do you think art—be that serial art specifically, or any medium—plays in urban policy discussions? I hope that doesn't sound like a naïve question, but there are so many things we take for granted when we live in urban environments that it's often difficult to imagine how a city would be outside of artists' imaginations, and very often those are employed in the service of urban developers.

My strips are just plans, little manifestoes, but for them to be enacted would take some kind of real action in the world. One of my strips can be a theoretical manifesto, but they're not always put into practice. That's a whole different, complicated question.

But I think it can turn the weight of public opinion, at least for the few people who read my strips and get these stories and realize what's going on on a certain level they might not have thought about. But changing things actually in the world is a multi-level thing. They all start as these paper manifestoes or dreams. You say, Look at this.

At my school we're collaborating with 350.org, the environmental action organization, and they're interested in having illustrators and cartoonists and animators come up with more compelling images of global warming than the Arctic melting. There are things happening in everybody's backyard that they could be visualizing. So I think there's a component of this kind of activity. But you know, my main activity is through comics. If I were an activist on some other level I'd probably be in prison now. It's a pretty risky thing to do.

As an artist and human being, what makes cities interesting? Why should we care about their survival, how they operate, and their meanings?

I think historically they were interesting because they were kinds of collective places with a lot of activity and cross-fertilization. I don't know if they function now in the same way as they did even when I was a child. I think a lot interesting stuff can happen in small towns and villages.

At least on the East Coast, there's this urban sprawl, and maybe it would be better if that were contained and the whole East Coast were not like a city. But things just aren't being made here any more—even that function of cities is kind of gone, like the garment district in New York. People were making clothing in midtown Manhattan, and since clothing is now mainly being imported, there are a lot of functions of the old city that don't exist anymore.

It's still a place to get an audience if you want to put on a concert or a show. There's a density of population that would give you an audience for a live show, and I think that's harder to do in a small town.

But as far as making things and reading and studying, a lot of great universities are in small towns in America, so it doesn't make sense to be in a big city. It's the most expensive place to do a lot of work. I tell my students to find a cheap place to live for 10 years so you can at least make some work.

In New York, at least when I was starting out, it was possible to live cheaply. That made a big difference in the amount of free time I had to make not overtly commercial comics, things that you just wanted to make and get into the world. So that's probably easier to do in a less-expensive real estate market. That's basically what cities have become—they're attractive entertainment places for affluent people. If you don't have money, you may be better off in a little town with a garden and less of a crushing overhead.

So I don't know. Toward the end of his life, [American comics artist] Will Eisner did this series about the city and it just seems so negative. It was somebody who just left and wanted to live in Florida. There's this one book about the contemporary city, and it's just somebody who hates everything going on there. And I try not to hate everything. But the clearest manifestation of everything bad in the economy happens in the city. There's all this money and there's this veneer of people who have these middle-management jobs who are perfectly happy going along with the status quo. Whenever there's a big demonstration in New York, there are people walking by looking at these demonstrators going, "What's the problem? I'm perfectly happy here. I have a good job. What are we complaining about?" There is this whole layer of, I don't know what you'd call them—middle management, upper middle management, executives—who are perfectly content.

I know young people coming in to teach at my school, even with full professorships, can barely afford to live in New York. It doesn't seem affordable to them.

These are ancient constructs, cities, and as they lose their purpose, they need to be rethought. This whole view that was in the "Knipl" strip of somebody living in a declining city, and the thing about a city in decline is that it becomes affordable. The manufacturing base has left and there was this moment in the '70s and early '80s when there was a lot of cheap places to live in New York. It was kind of living in the ruin of a city, but I would say an upscale city would not be a very nice place to live.

Finally, I wanted to ask you a bit about your writing, as it is as singular as your visual style—where does it take place in your process? I ask because I'm a words person, so I usually don't know what I'm thinking about anything until I start writing it. But you can do so much work visually that no amount of verbal information could. What influences or informs you as a writer?

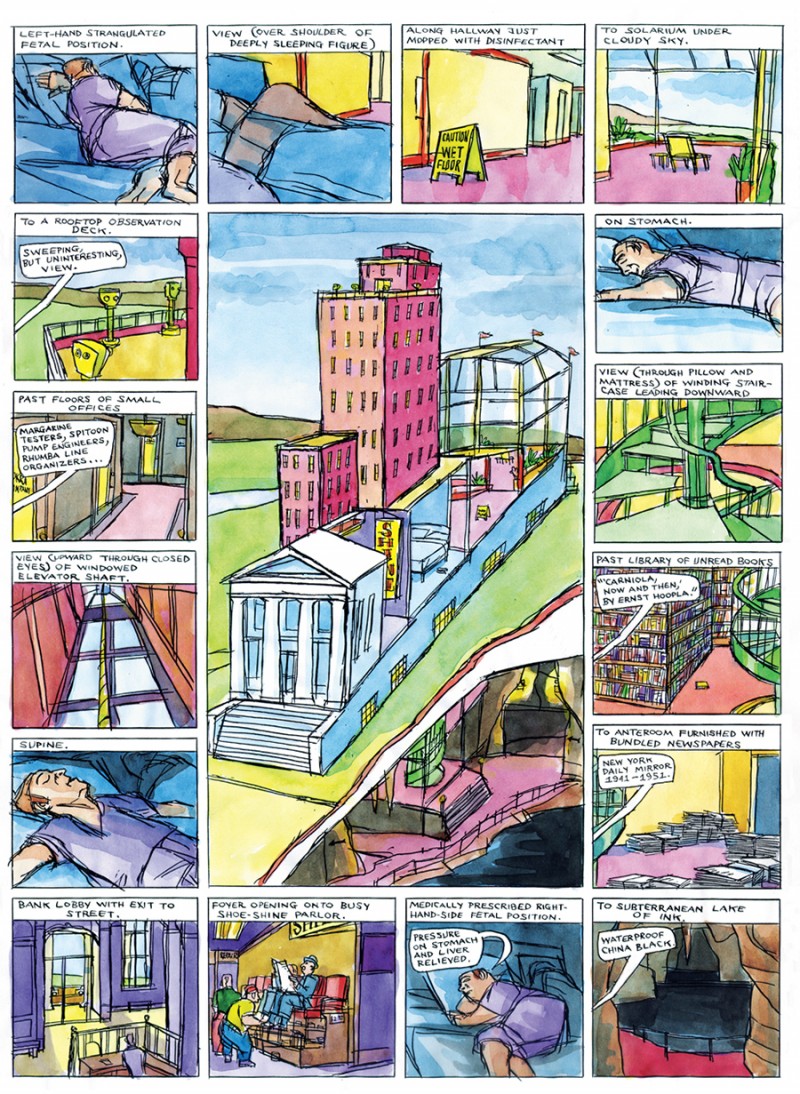

It's easier physically to write. It's just juggling these preexisting units of letters around. It doesn't have the same physical difficulty as making a picture. And you can juggle letters until you're blue in the face, so I do tend to write first because it's the easiest to do. I can do it laying in bed. I can do it on the subway. I can even do it walking in the street. You can compose sentences in your head, remember them, and when you get home they're going to be the same sentence. But if you think of a picture, there's nothing until it's on paper.

So I keep it in that kind of word flux where I can keep improving the ideas that I want to talk about. The picture making part—I have a whole history of western art to look back upon about how pictures can be made. But my comics are not just about picture making. I'm not a purist picture maker. It's about paper theater. It's about how words work with pictures.

But the writing is something I leave up to the last minute hoping I can come up with a better idea for the picture. I would never start thinking about a strip with a picture—it may be based on something I saw, but it's not my picture that would spark a picture. It's later, maybe the next level when I start drawing it, that I see things that I probably didn't think about, and it might change the way the texts goes. But it's like theater, it doesn't happen until its on the stage and you get to see it and hear it and look at it and you go back and rewrite.

Image caption: "The Insomniac's Mansion," Ben Katchor

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged homewood arts programs, comics, center for visual arts, art