One of the most famous stories about the development of literary and critical theory in the United States has its origin at Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus about half a century ago.

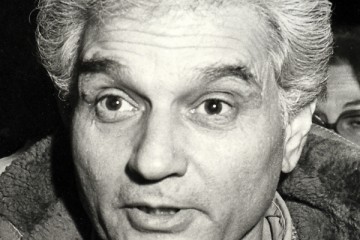

Image caption: Hent de Vries

It was at "The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man" symposium held at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library in October 1966 that a then relatively unknown French thinker named Jacques Derrida threw a wrench into a few of the central ideas supporting structuralism, a linguistic methodology for understanding and conceptualizing human culture dominant at the time and epitomized by luminaries such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, Louis Althusser, Jacques Lacan, and Roland Barthes. What's often forgotten about that event is that it was in fact the inaugural conference organized by Johns Hopkins University's Humanities Center, an academic department that celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

Yet the Humanities Center was never a hotbed for structuralism or poststructuralism—or exclusively French thought, per se, even though it played a historical role as a first conduit for "French Theory," as it is now often called. Rather, what guided the center then as now were the problems and questions, challenges and opportunities, that bubble up in between disciplines, those unconventional places where, say, political theory and anthropology overlap, or where the study of cinema, the study of art history, and the study of history and philosophy produce new insights. The center's faculty, visiting associates, postdoctoral fellows, and graduate students form a diverse international cadre from a variety of academic fields whose exploration of interdisciplinary pursuits takes them into uncharted terrain, often well before more discipline-oriented departments are willing and able to go there. In spite of (or thanks to) that broad profile, the department has succeeded in placing its graduates in a wide variety of disciplines, just as it has contributed to shaping the public face of the humanities.

To celebrate its half-century mark, center faculty and students organized the 50th Anniversary Conference, which runs Thursday and Friday at Levering Hall's Glass Pavilion. The event features 10 talks from a variety of international interdisciplinary scholars who are exploring tomorrow's questions today, including feminist literary critic Toril Moi; Michael Puett, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard; and world-famous Canadian photographer Jeff Wall. The full schedule of events and conference program are available online.

The Hub caught up with Hent de Vries, director of the Humanities Center, to talk about the center's departmental history, its resolutely eclectic intellectual pursuits, and its upcoming 50th anniversary.

"We hope the conference represents the best thinking that we have been historically and more recently interested in and also the kind of thinkers and intellectual style that we have been bringing to campus over the years," de Vries says.

Could you talk a bit about the origin of the center? I realize that the 1966 conference looms large in the imagination, both because of the people who were there and the subjects discussed, but I think that tends to overshadow the original impetus behind the creation of the center. Was its interdisciplinary approach to the history of ideas and exploration novel at the time among American universities?

I think it was. There have been other humanities centers, institutes, and initiatives, which did not acquire the eventual status of a department, just as there have been similar operations—think of Chicago's Committee on Social Thought, UC Santa Cruz's History of Consciousness Program, and Duke's Program in Literature—that, in spite of their peculiar names function as full-fledged departments, as we do. But there is no doubt that we have been and are still considered a maverick department, guided by the same principle of selective excellence that guides all departments at Johns Hopkins and with the same two or three tracks in humanistic studies that we have been fostering for decades: intellectual history, which has a long history at this university, going all the way back to Arthur O. Lovejoy; comparative literature, in which we have made excellent recent appointments with arrivals of Professors Leonardo Lisi and Yi-Ping Ong; and also comparative American cultures, which we have had on the books since the time when Professor Neil Hertz was still here. And the recent addition of Professor Anne Eakin Moss has guaranteed that we can cover Russian literature and the critical theorists that have been deeply influenced by it.

Yet I think the best way of clarifying what the Humanities Center stands for is to say that it is an interdisciplinary department that it is committed to problems and concepts, not to predetermined fields and schools of thought, much less specific methods. To give an example, we are not indebted to so-called continental philosophy more than we're interested in certain, but certainly not all, currents, figures and texts in so-called analytic philosophy. Next to Derrida and, say, Gilles Deleuze, we pay minute attention at least as much to a Wittgenstein and Stanley Cavell, to Richard Rorty no less than to John McDowell.

More broadly, what I think we have been trying to do, and what I think is beautifully formulated by one of our Humanities Center associates, Professor David Wellbery from the University of Chicago, is that we have been trying to reorient the field of comparative literature in its overall orientation. Comparative literature traditionally meant to compare national literatures, such as a German author and an Italian author in the same period. We have taken the modifier "comparative" increasingly to mean that we're interested in the ways in which humanistic studies, literature, expose themselves to—or even explore themselves—other fields of knowledge, meaning philosophy, approaches known from the history of science, the study of old and new media, even the archives of religion and theology. These kinds of borderline transgressions that exist between disciplines, that comparative study and intellectual history, newly defined, allow us to open up and systematically pursue several themes and topics, authors, and problems that were often not yet part of well-established fields and more traditional disciplines and that often eluded the departments in which they are housed. And, of course, the subjects we cover are very much related to the interests of the present faculty that happen to make up our group. That principle of wishing and being able to excel in selective topics has always been Johns Hopkins' strength much more than it is our apparent weakness.

I get the impression that the center was so associated with that conference that it, and Hopkins, was seen as the gateway to the U.S. for French thinkers, even though that was never its intellectual focus.

Exactly. People have often had the impression that we were some sort of an airlift between Paris and Baltimore. And yes, we do have a proud and long-standing exchange program with the École Normale Supérieure, but there are just as many faculty and student visitors and distinguished associates that have come from major American universities, just as they have come in recent years from the Middle East, from Israel and Palestine, from South Africa, and different parts of Europe.

So even though we began with this big bang of the structuralist controversy, as it has been called, we're never and will never be a structuralist or post-structuralist department, nor are we simply doing critical theory in the vein of literary or new criticism, cultural studies, or in the tradition of the so-called Frankfurt School of Western Neo-Marxism. And that makes us an eclectic operation, based on a positively valued strategic opportunism that comes with true innovation wherever it happens.

What we basically require from our students—especially the graduate students but also the postdocs and surely ourselves, as faculty—is to be, on the one hand, intellectually free and explorative—to have wild or bold ideas, as Karl Popper urged—and, on the other hand, to be simultaneously, firmly grounded in more traditional disciplines. Hence, most of us have joint appointments—in the departments of History of Art, History, and Philosophy—even though we try to pursue ideas that would not easily find attention elsewhere.

Likewise, we urge our graduate students to follow their individual interests, to begin with. And that may mean that they study more with other colleagues than our regular faculty or joint appointees. A unique feature of the Humanities Center is that our students have no required set of courses that they have to take with Humanities Center faculty. But while we encourage them to let their mind wander freely, at the same time, we recommend that they choose at least one disciplinary field and, thereby, qualify themselves for the real, existing job market, which is still very much dominated by traditional guilds. If you look at our track record, our list of distinguished alumni and graduate student placement, we have been quite successful in placing students coming from the Humanities Center, not just in critical theory programs or even comparative literature departments but also in history and art history, philosophy and religious studies, German and Romance languages and literatures, film and media.

You've described the center as a nerve center for exploration. Could you talk a bit about what you mean by that, be that here at Homewood or at large in the academy?

I think here at Homewood, what we have done in the last few years is further giving shape and context to our interests in the history of the sciences, for example. A couple of years ago, a colleague of mine, Professor Paola Marrati, together with Professor Jane Bennett in political science and Professor Veena Das in anthropology, organized a conference on new Concepts of Life, by which they meant not so much the latest in the empirical study or philosophy of biology or the latest in Foucauldian biopolitics, but really how it is that certain philosophies of life have come to play a much more prominent role now, whether via the lineage of Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze or through the renewed interest in the works of thinkers such as Georges Canguilhem.

We also brought a remarkable international scholar, Henri Atlan, based in Paris and Jerusalem, to Johns Hopkins for that same conference. Atlan has been one of the pioneers of information biology, but at the same time he was deeply steeped in the history of Jewish mystical thought and of the Spinozistic legacy that he sees as a kind of expansion of it. Out of that conference came a book series that was started by Todd Meyers, at the time a graduate student in anthropology, and one of our graduate students, Stefanos Geroulanos, currently a tenured professor in the history department at NYU. The series is entitled Forms of Living and is published to great acclaim by Fordham University Press. In the wake of the aforementioned conference, a group of our students also brought out a critical reader of Atlan's writings in that same series, collecting his technical thoughts on system theory and information biology on the one hand, and his several essays on the history of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism, on Spinoza, and on his own relationship to Judaism on the other. An interesting combination.

The second example of the Humanities Center's explorative aspect is our policy of appointing associates, distinguished visiting professors from the U.S. and abroad, for a period of three years. They come for intensive seminars and they're able to establish contacts with our students over long periods of time and often well beyond their actual visits. We brought Professor Sari Nusseibeh to campus who was representative of something that was always a desideratum for us, namely modern Islamic thought. There has been attention paid to the history of Islam and political Islam at JHU's School of Advanced International Studies, and there is the study of Arabic in the Near Eastern Studies Department, just as there is now ample teaching and research on Muslim societies and Islamic history in Anthropology and History. But there is no one teaching the archive of modern Islamic thought, raising the question as to how that tradition translates into guiding questions of philosophy and politics now. Nusseibeh, at the time the president of Al-Quds University, the only Arabic-speaking university in Jerusalem, came and visited and met with members of the dean's working group on Islamic studies. As a consequence of his visits, some of our students in the Humanities Center were invited by Nusseibeh to come teach classes or give lectures in East Jerusalem, in Abu Dis, and we are now bringing out a book, entitled The Concept of Reason in Islam, in the Stanford book series I am editing, based on the very lectures he gave here.

I think that was a very important event that took place, not least because it was a stimulus for the further formation of the now existing program in Islamic studies, which started about a year ago. I think that is another example of how we have been trying to catalyze certain ideas that exceed the narrow boundaries of intellectual history or comparative literature as they are more traditionally defined, in close cooperation with faculty in other fields in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

How has this project to redefine the "comparative" in comparative literature been? I ask in the sense that institutions and schools of thought in general can be slow moving ships, as it were.

What we have tried to do is be innovative and open to new impulses. Under the previous dean, there was an interesting process where all the departments were invited to write a white paper and to organize a Futures Seminar so as to "think big." And, as all departments did, we outlined some of the fields we wanted to move into, that included the aforementioned new concepts of life, Islamic thought and literature, and the developments in global religion and media, which has been my own interest in particular. We never felt we had to be defensive in the face of the often lamented crisis in the humanities. It always has seemed more important to us to be consistent in building a tradition of teaching and scholarship that bears its own demonstrable fruits. So many discussions now go in the direction of, on the one hand, public humanities and, on the other hand, global humanities. But it is fair to say that these can take different forms, and that there are different ways one can pursue those ideas.

To begin with the latter, when I came from the University of Amsterdam to the Humanities Center, two graduate students came with me, both from Philadelphia, who started their graduate training here and defended their theses with success. Kate Khatib and John Duda, in addition to taking their classes and writing their dissertations, were very committed to and remarkably effective in setting up Red Emma's. And we have had other students who have been very active in the city of Baltimore, at Twitter, or who founded their own translation agency.

In a different vein, over the years Michael Fried has organized a series of interviews and lectures by world famous photographers here and at the Baltimore Museum of Art. And I have been working with one of our former graduate students, Dr. Nils F. Schott, for the Fetzer Institute in Kalamazoo, Michigan, which is an philanthropic organization, and we ended up assisting in the production of an iPad children's book on the concepts of love and forgiveness, entitled Maggie and Her Magical Glasses. It has been awarded a prize and is for now sale on iTunes. We had planned it as a pilot project of sorts. So these are some of the contributions to the public humanities that we have made.

In terms of global humanities, if you look at our department in terms of its diversity and origins—our recent and current faculty have come from Latin America, East Asia, Italy, England, the Netherlands, Israel, and the United States—but especially at the cohort of graduate students, at the moment we have students from France, Brazil, Mexico, Lebanon, Iran, Israel, Turkey, and the Netherlands, and I fear I may be overlooking a few. We have just extended graduate offers that would make the group even more diverse than this. It is a very international cohort and community. And I think the challenge of the immediate future will be to constantly rethink and reshape the study of the humanities, which we are now trying to do with a revamped and revitalized undergraduate curriculum in humanistic studies and human values. This will be our strength and point of attention, no matter how much we welcome new initiatives in connecting the fate of the humanities to that of the local community on the one hand, and of the so-called global humanities on the other. The proper balance here is to nourish and solidify existing strengths while being open to new initiatives as they present themselves beyond the fashionable.

Indeed, fashionable we've never been. Just as we were never into structuralism and traditional critical theory, much less cultural studies or continental philosophy, as I explained, we never got onto the bandwagon of so-called new historicism, new materialism, cognitivism, and the like. We have stuck to a long-standing agenda—which is to always insist on the best of critical and normative thinking, on the European end of things, and on the strengths of conceptual analysis and pragmatism, but also transcendentalism and moral perfectionism, on the Anglo-American side of things. And I hope that's what we'll continue to do, now that we have just undergone an excruciatingly detailed process of internal and external review by distinguished peers—with rave reports and supportive recommendations to boot—and are now trying to rise to the occasion to replace two stellar retiring colleagues, Professors Ruth Leys and Michael Fried. Both have contributed in invaluable ways to our reputation and brand name and will, no doubt, continue to do so in more indirect ways as newly appointed emeriti professors and newly elected members of the Hopkins Academy.

Tell me a bit about the upcoming conference. What was the center thinking about when organizing it?

We had several options. One possibility would have been to have a commemorative conference reflecting on the thinkers who were there in '66 and to ask ourselves what has been done in terms of studying their work ever since. That's something we decided not to do for this occasion. I'm now in conversation with colleagues at École Normale Supérieure and at the Sorbonne to set up two international workshops—one in the fall in Paris and the other in the spring of 2017 at Hopkins. Those workshops will be on the '66 conference and analyze it not only in its own right but also as the beginning of traveling theory, la pensée voyageuse, and indeed as the significant influx of French thought into the United States. The question would be: How can we take stock of what happened then and who would be the figures carrying its agenda further?

The other option would have been to do something about the larger history of the humanities and how Hopkins has played a pivotal role in it, copying the model of the Humboldt University in Berlin and the famous unity of research and teaching (Einheit von Forschung und Lehre), and how the center, in particular, has functioned in that. Together with professor Stephen Nichols and Vice Dean Chris Celenza, I'm one of the co-organizers of a conference devoted to the Making of the Humanities that will take place in the early fall at Homewood that will be devoted to these broader questions. That conference will be a more historical investigation of individual fields, including comparative literature, and I will speak on the history of the Johns Hopkins Humanities Center on that occasion.

But we decided that in celebrating our 50th anniversary we would craft a conference that would not follow the topics of the '66 conference nor the theoretical paradigms that were queried there. Instead, we asked ourselves, if we were to organize a conference in 2016 that would make some sort of a splash now, who would we want to invite? In other words, if this were to be a conference inaugurating the next 50 years, say, which thinkers would we consider to somehow set the tone for conversations whose precise subject or direction we don't even know yet? That was the idea. We felt that to mark our 50th anniversary, it would be important not to be self congratulatory, much less nostalgic. After all, we should be looking for new impulses even in the full awareness that the Humanities Center has acquired a certain historical and current presence.

Strangely enough, I have always had the distinct feeling that the Humanities Center is better known outside of Hopkins than inside. It seems as if we always have to explain more at home. And yet our legacy and departmental name has become some sort of a brand name that, we are often told, is profitable to other departments in the humanities and social sciences in the School of Arts & Sciences in terms of attracting and retaining students and faculty as well.

Perhaps this reputation beyond this institution is also an effect of our placement record of which we keep careful track, just as it is reflected in the graduate student applications that we continue to receive as well as in the multiple requests from individual scholars who come from abroad, often with their own graduate or postdoctoral stipends and fellowships. There is a reason we were sought out by the Dahlem Humanities Center at the Free University of Berlin to coordinate an international network, devoted to Principles of Cultural Dynamics, fully sponsored by the German Academic Exchange Service, or DAAD, that brings scholars in all stages of their career from Baltimore to Berlin and vice versa, allowing them to interact with peers from Harvard, the École des Hautes Études, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and the Chinese University of Hong Kong as well.

In sum, then, this is where we see our strength, something I think is quite remarkable and what I'm most proud of. Our faculty and distinguished visitors, our graduate students and postdocs, even though they come from very different backgrounds and have different intellectual research topics, form an intellectual community in the best sense of the word. There are certain common references—authors all have read, concepts and problems all would be familiar with—and that are investigated in a completely nondoctrinal, nonideological way. We're not a school—far from it. And we're not advocating one method, because we have very different scholarly sympathies and agendas. But there's a very strong sense of this being a congenial department and an open-minded as well as welcoming unit on campus. And, God knows, in any university and school with an avowed commitment to the humanities, that's not only something to be collectively very proud of but also something to cherish.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged critical theory, johns hopkins humanities center, intellectual history, humanities