When award-winning director Ava DuVernay made a film that Hollywood studios didn't want, she launched her own distribution company.

After making three indie dramas, she cultivated a small but devoted fan club and a Best Director award at the Sundance Film Festival, the first black woman to receive the honor.

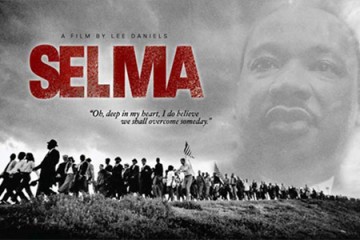

Then came Selma, the 2014 historical drama that chronicles the 1965 voting rights marches, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. The film earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture, the first film by a black female director nominated for the honor.

For DuVernay, it also opened access to unlimited budgets and paved the way for new partnerships, including an upcoming original series on the Oprah Winfrey Network.

"After you make a hit, everyone likes you," DuVernay joked to an audience that visited Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus Tuesday evening to hear her speak as part of the Milton S. Eisenhower Symposium. "As long as people want to hear the story, there's room."

A Compton, California, native, UCLA African-American studies grad, and former film publicist who launched her own public-relations agency, DuVernay followed a path to film that was nothing short of unusual.

"It was scratching, scraping, like soul-crushing experiences every step," she told Baltimore writer D. Watkins, who facilitated the conversation.

DuVernay was on set one day when she thought, "If they can do it, I can do it," she said. The $50,000 she had saved for a house went toward the production and distribution of the independent drama I Will Fall. That's when she launched her distribution platform, known today as Array, which supports films by women and minorities.

Some 50 years before DuVernay recreated in Selma the historical events that culminated in the passage in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, her father, a Lowndes County, Alabama, resident, witnessed real history unfold.

"I had a real intimacy with the place," DuVernay said. Her mom, who works in Selma today, crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge—the site of Bloody Sunday—every day.

Using an original screenplay by British screenwriter Paul Webb, DuVernay expanded the narrative. "There were nuances that were missing," she said. "Like women."

As a filmmaker, DuVernay said, it was important to know what motivated those who took part in the historic marches, the moments of violence that propelled them. "The same way we're motivated by Eric Garner, or Freddie Gray, or Walter Scott, or Trayvon [Martin]," she said.

That segued into a discussion about Black Lives Matter. Watkins asked what parallels she saw in today's movement and the one she depicts in Selma. "Like-minded people, black people and allies, brown people, fighting and raising their voices for justice," she replied, though she added that the movements themselves are very different.

"There was a time when black people couldn't have a pencil, and now we all have a camera in our pocket," DuVernay said.

When the floor opened up for questions, self-described movie-geeks and fan girls rushed the microphones, seeking advice and expressing similar grievances about an imbalanced industry.

One attendee said she has a DuVernay quote plastered on a wall in her bedroom: "If your dream only includes you, it's too small."

To DuVernay, that means hiring a friend who dreams of a career in craft services to do on-set catering, and then some.

"It's saying, 'Wow this image that I'm creating, this story that I'm telling, people are going to see this, and it has power,'" she said. "What should it say beyond me?"

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged diversity, film, mse symposium