A team of Johns Hopkins specialists has gathered evidence of accumulated brain damage in former NFL players that could be linked to specific memory deficits experienced decades after the men stopped playing the game.

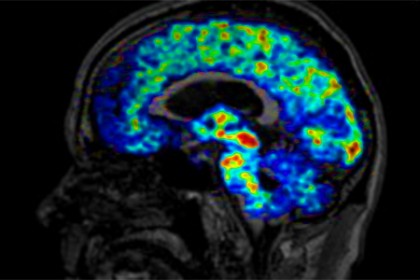

Image caption: The brain of a 66-year-old former NFL player shows increased binding of the translocator protein across many brain regions compared to binding seen in healthy controls.

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

The small study, which involved imaging and cognitive tests of nine former NFL players, provides further evidence of the potential long-term neurological risks to football players who sustain repeated concussions. It also strengthens the argument of those calling for better player protections.

Results of the study are published in the February 2015 issue of the journal Neurobiology of Disease.

"We're hoping that our findings are going to further inform the game," says Jennifer Coughlin, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "That may mean individuals are able to make more educated decisions about whether they're susceptible to brain injury, advise how helmets are structured, or inform guidelines for the game to better protect players."

Several anecdotal accounts and studies have suggested that athletes exposed to repeat concussions—including collegiate and professional football, hockey, and soccer players—could suffer permanent brain damage and deficits from these events. However, the mechanism of damage and the source of these deficits have remained unclear.

To understand them, Coughlin; Yuchuan Wang, assistant professor of radiology and radiological science at the JHU School of Medicine; and their colleagues used tests to directly detect deficits and to quantify localized molecular differences between the brains of former players and of healthy people who didn't play football.

The researchers recruited nine former NFL players who retired decades ago and who ranged in age from 57 to 74. The men had played a variety of positions and self-reported a wide range of concussions, varying from none for a running back to 40 for a defensive tackle. The researchers also recruited nine age-matched "controls"—healthy individuals who had no reason to suspect they had brain injuries.

Each of the volunteers underwent a positron emission tomography, or PET, scan, a test in which an injected radioactive chemical binds to a specific biological molecule, allowing researchers to physically see and measure its presence throughout the body. In this case, the research team focused on the translocator protein, which signals the degree of damage and repair in the brain. While healthy individuals have low levels of this protein spread throughout the brain, those with brain injuries tend to have concentrated zones with high levels of translocator protein wherever an injury has occurred.

The volunteers also underwent MRIs, which allowed the researchers to match up the PET scan findings with anatomical locations in the volunteers' brains and check for structural abnormalities. In addition, participants took a battery of memory tests.

While the control volunteers' tests showed no evidence of brain damage, PET scans showed that on average, the former NFL players had evidence of brain injury in several temporal medial lobe regions, including the amygdala, a region that plays a significant role in regulating mood. Imaging also identified injuries in many players' supramarginal gyrus, an area linked to verbal memory.

While the hippocampus, an area that plays a role in several aspects of memory, didn't show evidence of damage in the PET scans, MRIs of the former players' brains showed atrophy of the right-side hippocampus, suggesting that this region may have shrunk in size due to previous damage.

Additionally, many of the NFL players scored low on memory testing, particularly in tests of verbal learning and memory.

Though the researchers emphasize that this pilot study is small in size, they say that the evidence suggests that there are molecular and structural changes in specific brain regions of athletes who have a history of repeated hits to the head, changes that remain decades after their playing careers have ended.

The researchers are currently looking for translocator protein hotspots in both active and recently retired players to help determine whether these changes develop rapidly or whether they're a result of a more delayed response to injury with similarities to other degenerative brain disorders.

If these findings are seen in studies with larger numbers of participants, they say, the molecular brain imaging technique used in this study could eventually lead to changes in the way players are treated post-concussion or perhaps in how contact sports are played.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged head injuries, concussions