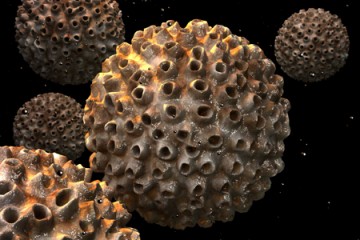

In "The Virus That Owns the World", Johns Hopkins Public Health magazine examines scientists' efforts to better understand human papillomavirus, or HPV. The virus has been linked to half a million cases of cervical cancer worldwide each year, and more recently has been associated with a sharp increase in head and neck cancers, particularly among men.

HPV, the author notes, "currently infects about 79 million Americans and will infect, at some point in their lives, almost every sexually active person."

The article focuses on the work of Keerti Shah, a leading HPV researcher and professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and that of his his protégés. Together, they have greatly advanced our understanding of HPV, where it comes from, and how it spreads.

In 1999, Shah proved that HPV is responsible for essentially 100 percent of cervical cancers in all parts of the world. It's the only example of a major human cancer that has a single cause—a fact that led to the development of a preventive vaccine recommended for adolescents since 2006. A "completely effective vaccine," Shah notes, albeit one that's still too expensive for use in Asia, Latin America and Africa, where most of the 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer occur each year, and 200,000 people die annually from the disease.

Increasing immunization rates, both in the U.S. and worldwide, and creating a better understanding of the virus among health care providers and patients are ongoing challenges.

Read more from Johns Hopkins Public Health magazineShah's great strength, [Shah protégé Patti] Gravitt explains, is keeping his eye on the public health focus: "Everything he does is directed toward trying to make sure we don't get distracted by some random detail. Everything comes back to: Does it matter? Does it save lives? A lot of the work we did together was to develop methods to better detect and screen for HPV; to build a better mousetrap. Keerti's push now is to get people to use the mousetrap."

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged cancer, epidemiology, hpv, cervical cancer, keerti shah