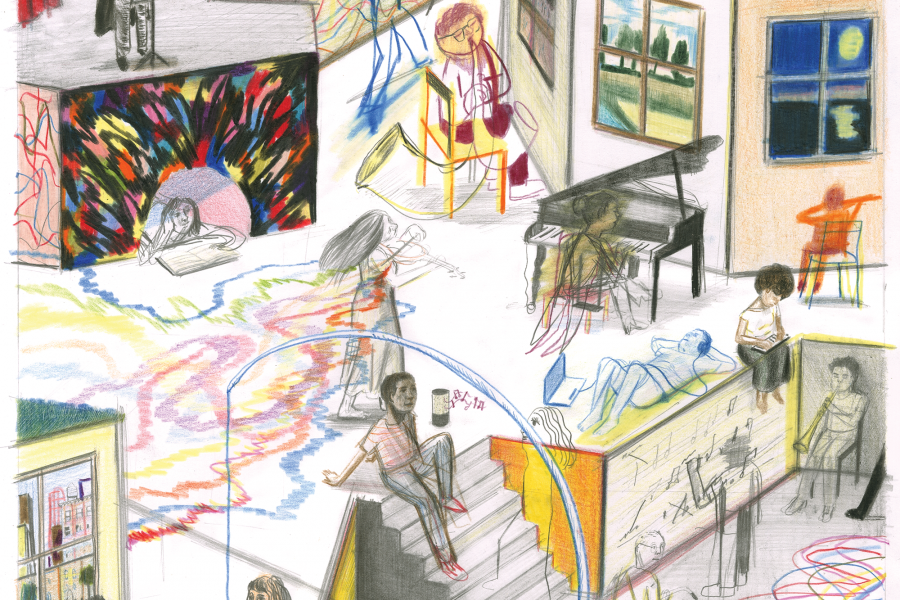

Saxophonist Tyrone Page Jr. couldn't decide what music he wanted to play for his upcoming performance. By early summer, Page was feeling drained. He was only halfway through his second year as a middle school band director in a Baltimore suburb when the coronavirus pandemic closed schools and he had to figure out how to do his job online and on the fly. Page, Peab '16, '18 (MM), also conducts the Peabody Preparatory Wind Band, and he witnessed how the pandemic had profoundly discombobulated his students—and his own creative drive.

"It was really hard to maintain structure or have motivation when I don't have anything to look forward to on my calendar," he says. "Dealing with the pandemic and the political unrest, police brutality, and racism that I woke up to each day made it more difficult to get up, practice and prepare music, or create art as usual."

As a member of Mind on Fire, a Baltimore-based ensemble started by a few Peabody alumni in 2016, Page was slated to perform as part of a variety show at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in July. Originally conceived to take place inside the Pratt's neoclassical Central Library building in Mount Vernon, the concert was rethought as a prerecorded video to maintain physical distancing. Individual performers recorded pieces at their homes that the ensemble stitched together for a livestream. Mind on Fire organized a diverse array of poets, jazz musicians, movement artists, R&B singers, as well as classical musicians for the event. Still, "for whatever reason," Page recalls, "there was nothing that I felt like performing or that I cared to prepare."

Chances are we've all endured bouts of mental fatigue and attention span–zapping exhaustion living through the past six months. For performing artists, that anomie can infect one's identity. Although most music fans only see what takes place onstage, there are hours, days, weeks, and months of collaborative rehearsals and preparation leading up to each performance.

Mind on Fire is a "new music" ensemble, an umbrella term for a broad creative terrain of conservatory slash classically trained artists who work with popular music and other art forms, and perform in untraditional venues. Like underground music in general, new music doesn't have the institutional resources or command enough market power to force changes in classical music writ large, but new music artists are the ones most actively and willingly able to try out an idea just to see what happens.

And exciting possibilities are bubbling up from this exploration right now. Musicians and composers are collaborating in new and different ways. Ensembles are checking out different instrumentations and repertoire. And they're all experimenting with what online performances look like now and in the near future. It is way too early to tell if any of this experimentation is going to prove transformative for classical music in the long or short run. But for young artists beginning to forge careers in classical music and opera, which have faced existential crises to their business models since the tail end of the 20th century, this moment is encouraging artists to take the time to rethink what classical music and opera could be.

Composer James Young, Peab '14 (DMA), Mind on Fire's executive director, considers this moment a tempering tool for the ensemble. Young and seven other musicians started Mind on Fire to spotlight living composers and showcase classical music alongside other contemporary arts. They aim to do so by prioritizing marginalized voices, collaborating with all kinds of performers, and bringing contemporary classical concerts into venues outside the traditional recital hall. With venues closed, they're having to find new ways to pursue that mission.

"I hope we can continue keeping things weird, and play with what we have available to us right now," Young says, mentioning both Mind on Fire's recent variety show and a performance he'd seen at a music festival that went virtual owing to the pandemic. The piece was titled ["👽 💅"]—read: "alien nail polish"—and features a saxophonist responding to the electronic blips and beats orchestrated by a 30-something composer. The result is equal parts video game soundtrack and electroacoustic dance music, and it may be better experienced on a laptop than in a symphony hall. "I hope that we and other ensembles and artists lean into this moment and emphasize thinking about the venue that is the computer screen," Young says. "It's something that can be explored, not an impediment."

Before the coronavirus landed on U.S. soil, orchestras and opera companies already faced a battery of obstacles: fundraising, struggling to gain new audiences as its season ticket holders age, navigating contract negotiations with musicians' unions, and continuing efforts to reinvigorate a concert rep canon that favors the familiar over more contemporary or varied fare, as well as simply being perceived as old, elitist, and overwhelmingly white. The pandemic initially appeared to be the straw that broke the art form's back. In March, the website OperaWire.com started tracking season postponements and cancellations in the U.S. and Canada. The last update was May 17, by which time more than 100 orchestras and opera companies, concert series, and festivals had announced cancellations that stretch into next year. In June, both the New York Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic announced that performances wouldn't resume until after January 6, 2021. That same month, the Broadway League, the trade organization of theaters and producers, announced that its show calendar, which went dark March 12, would be canceled at least through the end of the year.

Many musicians turned to the internet in some form as their paying gigs evaporated. They individually recorded their own parts of pieces to be digitally stitched together to create virtual ensemble performances. Solo artists and musicians sheltering together held recital-like concerts in their homes and apartments. Large orchestras and opera companies turned to their recordings of performances and productions and streamed them online. Some virtual "concerts" were free, some artists accepted donations through virtual tip jars using online payment systems like Venmo, and some performances were ticketed through websites such as GroupMuse.com.

This wide-scale shuttering and digital pivot prompted an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal to call the pandemic a "rolling catastrophe for all of the performing arts," particularly for classical music. It goes on to call for classical music to use this moment to build relationships with new, younger potential fans and make use of its "tremendous inventory of recordings and videos of real, not virtual, performances" instead of relying on the "pandemically clever Zoom ensemble performances."

Thing is, online audio/visual cleverness is part of the vernacular of 21st-century music and art creation and consumption, and some of the most compelling online performances created during the pandemic thus far are quite playful and imaginative. In 2014, Alarm Will Sound, the NYC-based chamber orchestra that's successfully combined new music with indie-rock impishness and a theatrical flair, premiered composer John Luther Adams' Ten Thousand Birds as a 70-minute piece in an outdoor urban plaza in St. Louis. Adams was inspired by birdsongs heard in nature, and the ensemble's performance evoked that warbling musicality of walking through the woods. In June, the ensemble released an under-six-minute arrangement of Adams' piece filmed in a single take inside a New York apartment, with individual performers appearing on 27 different screens scattered about the rooms as if birds perched in the kitchen sink, above windows, atop door frames, and on the fire escape outside a window. It's a lovingly offbeat, absolutely entertaining, and ingenious way to reimagine the piece for a small screen.

It also required a fair amount of digital media preparation and technical know-how to pull off, skills that haven't traditionally been part of a classical music education. About 10 years ago, audio engineer Ed Tetreault, Peab '05 (MA), manager of the Peabody Institute's Recording Arts and Sciences program, started a yearlong class called Recording for Musicians, which aims to teach music majors the basics. "I've been pushing the idea that every musician has to have some level of recording chops for a long time," he says, pointing out that since the late 1990s the quality and relative accessibility of home recording software and hardware have empowered musicians in other genres to have more control over their creative labor. He started the class because he thought classical musicians shouldn't have to rely on an audio engineer for basic recording needs either. Classical musicians could do that themselves.

A DIY approach has been a bedrock of punk, hip-hop, and dance music since the 1970s, jazz since the 1950s, and Black musicians' touring circuits since at least the 1930s, but it's relatively novel in America's classical music communities. Conservatories such as Peabody started understanding this skill set as a fundamental for today's music careers, and the pandemic has accelerated and reinforced that realization. For the foreseeable future, musicians may be recording their own auditions and their own home concerts, and collaborating remotely. They need to be adept at recording themselves competently, which involves teaching their ears to hear differently.

Musicians, Tetreault says, are amazing at listening to music and analyzing its musicality: tempo, phrasing, wrong notes, timing, and so forth. "One of the skills that I want to develop in them is the ability to listen technically," he says, meaning like an audio engineer does. "We're listening to completely different aspects of sound."

Scott Metcalfe, director of Peabody's Recording Arts and Sciences program, compares technical listening to how the ear transmits sound to the brain. The eardrum is vibrated by sound waves, which are amplified as they pass through the tiny middle-ear bones and reach the cochlea, where they are converted into electro-chemical signals that travel the auditory nerve. "Your brain is constantly working with the mechanism of the ear to refine what you're hearing," Metcalfe says.

Think about it: We unconsciously tune out the sound of the air conditioner when we're watching TV. "Your brain processes sound and says, 'I need more of that, I need less of this, I want to hear what's coming from over there and not what's coming from over there,'" Metcalfe says. "A microphone doesn't do that. The microphone is basically our eardrum and the amplifier that's next to it. We have to be the brain for it."

Tetreault's course provides musicians with the fundamental knowledge to be that brain. Students begin the year learning acoustics before Tetreault takes them through the entire recording process from microphone placement to editing, mixing, mastering, and distribution of a final product. The end-of-class project is to spec out a recording studio. He'll give them some basic parameters, "You need to be able to record up to eight musicians at once and you've got a $12,000 budget, go for it," he says. "They basically build their own studios, which is a lot of fun."

Zane Forshee, Peab '01 (MM), '03 (GPD), '11 (DMA), and Tariq Al-Sabir, Peab '15, taught themselves such skills, which have become woven into their creative practice. Forshee, a Peabody faculty member in Guitar, turned to classical music after getting into punk. He recorded his own solo classical guitar albums and booked his solo tours. When he and his wife had a child in 2013, he started experimenting with a laptop tour—him, his guitar, and broadcasting his roughly 30-minute concert online—performing in just about any space he could. Soon, contemporary concert halls that wouldn't book his solo guitar shows were inviting him to demonstrate what he was doing for other younger artists and students.

"That's when I started realizing, 'OK, this isn't something that I was ever taught, but younger musicians see something here,'" Forshee says. "I started to realize that we as educators need to evolve, too—and more people are realizing it now because it's a huge shift. Just looking at this moment from a business standpoint, I can't be waiting two years to play a concert because that's when I'm getting paid next."

Al-Sabir, who is a 26-year-old vocalist, composer, producer, and music director, is a member of that younger generation of digital natives who grew up experiencing music in the genre-flattening record store of the internet. He started writing rap verses and choruses in the third grade; for his 10th birthday his grandmother gave him an electric keyboard that devoured his spare time. By seventh grade, he'd filled several notebooks with his songs, raps, and a musical, and his participation in Peabody's Junior Bach program led to composition study at the Preparatory. He learned to record his own music out of necessity. Pop, gospel, musical theater, hip-hop, R&B, classical—Al-Sabir remains interested in creating it all. "I believe I am a product of a generation of musicians who aren't totally abandoning all the rules but are certainly abandoning the ones that don't make sense to them," he said during his 2017 TEDxMidAtlantic talk. "We're using the world to make our own curriculum."

Last year, Al-Sabir debuted #UNWANTED at the Shed at Hudson Yards in Manhattan. #UNWANTED is a multimedia, genre-fusing song cycle with movement and visual accompaniment that explores how Black millennials navigate the digital realm. "I'm aiming to shed light on our experiences and what that means in a larger context, a desire to create a virtual home where there might not be a physical one," he says.

That virtual realm may be a space today's emerging artists understand more implicitly than their teachers do. Peabody Recording Arts faculty Metcalfe and Tetreault both mention that while some aspects of remote teaching are cumbersome—Tetreault notes that it's difficult to talk about audiophile quality sound when he can't demonstrate inside Peabody's high-end recording studios—they've all been surprised how some class projects and lessons work just as well, if not better, online. Both were impressed with the results of teaching students editing and mixing one-on-one. Student and teacher can share screens with each other, listen to sound files, and watch what edits are being made in real time. "The mixes that I got this past semester were some of the best that I've received, so I'll be doing more of that in my teaching," Tetreault says. "What was also really cool about that was watching a student realize, 'Hey, I can do this stuff on my laptop with my own gear. It'd be nice to be in a studio at Peabody, but I can also mix a virtual orchestra at home.' And they did."

Forshee is also the chair of Peabody's Professional Studies Department and director of LAUNCHPad, which houses the school's suite of career services. LAUNCHPad assists students and recent alumni with the nonmusical aspects of their careers, such as building digital portfolios, programming, and audience-building. And he's witnessing career models change from the era of the soloist who performs only in concert halls to one where "more and more successful artists do many different things," he says. "However we end up doing this kind of work online is going to be every bit part of the audience-building experience that the in-person concert was before. People who are going to succeed will understand how to build both of those worlds together in an authentic way that allows engagement on both sides."

Tariq Al-Sabir teaches music to underserved students in Brooklyn. Like Metcalfe and Tetreault, he's noticed some aspects of teaching recording arts worked tremendously well online and became a great deal of fun for the students. But he's also cautious about identifying technological solutions for challenges facing classical music performance and education right now, as it could introduce another barrier to engaging with the art form.

"When we have these conversations about technology, we must include an assessment of accessibility at every step of the way," he says. He mentions a colleague who worked to get students a learning device so they could join online classes. "And I'm thinking it's one thing to make [class] available online, but how do I transform my teaching to make it effective, too? I was already thinking I need to recalibrate what changes need to be made in my own career for the long term to survive this [moment], and that means thinking about performances and my teaching as well. Accessibility isn't a new conversation in classical music at all, but if you want to talk about how healthy this industry is going forward, it has to be a priority."

The co-founders of the Mind on Fire ensemble agree. As much as they're thinking about how they can continue to create digital content that engages and builds on their audience base right now, they're also examining how their organization operates. Allison Clendaniel, Peab '12, the ensemble's co-artistic director, vocalist, and multi-instrumentalist, says such reflection led the group to think less of themselves as a new music ensemble and more as a collective of highly trained musicians who are interested in a number of different aesthetics. "To that end, one of the things we're trying to figure out is how to be an organization with a very small operating budget that wants to attract equitable leadership among Black and Indigenous people of color when we don't have enough money to provide a fair wage for anyone on the admin staff," she says.

"We don't assume we're going to come up with a perfect anti-racist framework for our organization during this time," adds Mind on Fire technical director Jason Charney. "But we want to do enough work so that when we can start thinking about organizing concerts again, we can reach out to like-minded organizations and artists and not just seek their advice and expertise."

This ongoing examination of career trajectory is a process that mezzo-soprano Megan Ihnen, Peab '09 (MM), believes new musicians regularly have to do. Now based in New Orleans, Ihnen collaborates in a voice and saxophone duo with Alan Theisen that, prior to the pandemic shutdown, performed at colleges and conservatories, public libraries, private homes, and other small venues. She also provides strategy and communications work for individual artists, the contemporary chamber ensemble Nief-Norf, as well as the nonprofit organizations New Music USA and the Live Music Project.

She started a coaching and consulting service for musicians also interested in building careers outside the traditional classical music trajectories. For her, that means talking frankly about the good and the bad. "Every musician is a biological instrument, especially voice," she says. "And sometimes that window of time where your voice does what you truly want it to do doesn't last as long as other instruments. I don't want to oversell myself as being fantastic, but when your stuff is starting to click, you feel you're able to make career moves."

The pandemic, Ihnen worries, could be the event in an emerging artist's career that makes them think, I missed my shot. "That's anxiety talking, and it's not helpful," she says, adding that it's one of the reasons she hasn't dived into all the online new music activity taking place right now as a performer. Artists may be trying to do whatever they can because their concert careers came to a sudden, abrupt stop. "I'm really excited to see people get more creative with how they're putting more life into the music that we're experiencing through the screen. That part is very interesting to me, and I think I'll engage more with it soon. Because we're still so early in this, though, and I don't think I'm alone in feeling this way, but I think there's still so much of our brains and our bodies that are trying to process and deal with this moment that I don't want to point to anything that may be a trauma response and say, 'Look at how creative this is.'"

Let's make one thing nice and clear: Nobody I spoke with believes a virtual performance is ever going to rival, much less replace, the real thing. Whether it's the surge of instruments tuning to a concertmaster's violin or a bolt of anticipation that runs down the spine when the house lights go down before a headliner comes on in a club, concerts convey too many intoxicating intangibles that can't be re-created in our physically distanced online worlds. Musicians are as hungry to get back onstage as fans are to see them.

Also, this consideration of performance during a pandemic contains two giant holes that haven't been addressed at all: the uncertainty facing arts funding and music venues in the immediate future. It's impossible to guess how the ongoing economic downturn will impact institutional and nonprofit philanthropy and individual giving in 2021 and beyond. We're sadly already witnessing the decimation of music venues around the country. In May, the National Independent Venue Association surveyed its nearly 2,000 members and found out that 90% fear they'll close permanently without federal assistance. And it's a little terrifying to consider rethinking your art form if there's nobody to support it or places to do it.

Which is why it was somewhat surprising to hear how low-key hopeful the musicians I spoke with are right now, a hopefulness succinctly captured by the Haitian-American, Grammy- nominated flutist, vocalist, and composer Nathalie Joachim in her keynote address at the 2020 New Music Gathering in June. This volunteer-organized annual festival started in 2015 to bring together artists interested in the creation, performance, production, and promotion of new music. Peabody hosted the 2016 festival, which included a keynote address by Marin Alsop and a series of concerts, panel discussions, and a group discussion about how musicians can be better allies to artists coming from different backgrounds, experiences, cultures, and identities.

The 2020 Gathering, naturally, took place online, and Joachim delivered the talk from her home in Chicago. She wanted everybody to know up front that she had good news and bad news. The bad news was obvious: We're living in a global pandemic, dealing with racial injustice, the Earth is screaming, people are living in extreme poverty, and that's just the tip of the iceberg. As far as bad news goes, she said, it doesn't get much worse than where we're at. At least, she hopes it doesn't.

The good news: They—the new musicians watching from their homes around the country—are still here, creating, and this moment is an enormous opportunity to push their industry for ward and tell stories that need to be heard.

"I was crying during her speech and it gave me something I just needed to hear," says composer, musician, and educator Ruby Fulton, Peab '09 (DMA). Fulton co-founded the Rhymes With Opera company in 2007 with soprano Elisabeth Halliday, A&S '07, Peab '07; composer George Lam, Peab '05 (MM); soprano Bonnie Lander, Peab '07 (MM), '08 (GPD), '09 (GPD); and baritone Robert Maril, Peab '04 (MM). RWO has commissioned more than 17 new operas since it started, and very early in the pandemic it made the decision to postpone its annual main production at the Flea Theater in Tribeca to 2021 and curate a cyber season this year that's proved quite versatile. It held an online watch party for its video opera Adam's Run. The founders adapted their salon series that spotlights composers and performers for the web, freeing them from having to bring musicians together in a physical space and allowing them to focus on new music activity around the country. They put together an online listening slash dance party for the release of remixes of the soundtrack for the RWO opera Rumpelstiltskin. They put together an online workshop for emerging composers, and in September they're debuting a bunch of a cappella one-minute operas they commissioned during the pandemic.

And they're starting to see how their online programming, while fulfilling a need right now, creates opportunities that they didn't consider before. "I always considered our season as lots of cool things, but the big thing is the main stage performance," Halliday says. "What's emerging is that other aspects of our mission and our values have transitioned more easily to this current context. The education component, the [composers] workshop, we've been talking about doing it for years. And the community-building component, which is the salon series, now we're thinking, We could do this every month in a different region of the country."

Lander adds that the pandemic has reminded her why she wanted to start RWO in the first place. "We started this DIY opera company as a way for us to work together," she says. Over the years, as careers took founders to other cities, the company did become more focused on its annual main stage production. "Now we're collaborating again on this cyber season, doing all these little projects that we might not have thought to do if we didn't have the impetus to do it."

Finding or rediscovering what scratches that creative itch during the right now is slowly becoming the kindling for the next bodies of work new music artists will be thinking about and exploring. Tyrone Page Jr. eventually settled on composer Alexandra Gardner's Tourmaline for computer and soprano saxophone that he adapted for his tenor, and his gorgeous, fluttering performance led to Page's being invited to perform at upcoming virtual concerts. Zane Forshee is considering reaching out to friends and colleagues to commission a series of short pieces of home recordings to capture what's been on people's minds during their time sheltering in place. And Tariq Al-Sabir was commissioned to create a piece of sound art for Columbia University's Wallach Art Gallery to accompany an upcoming exhibition that puts contemporary artists in dialogue with the Harlem Renaissance.

Even though they can't get on a stage and share their work with audiences right now, they're still finding ways to create. "I highly encourage people who engage with the arts to be a witness for the creatives in their lives during this moment," Megan Ihnen says. "As people start to move in this virtual space and make things again, pay attention because it's going to be exciting when you start to see artists figure out how to do new things. That's what I love seeing—when people try new things or team up with new collaborators and the lightbulbs go off in their heads. That's when the magic starts to happen. I know when that happens for me that's when I think, Yeah—that's the good stuff."

Posted in Arts+Culture