Let's be honest: We all may not age as seamlessly as Jane Seymour and Rob Lowe. Eventually, wrinkles and lines will appear on our faces. Hair will fall out. We'll go gray. But one long-alleged side effect of aging, high blood pressure, may not be a fait accompli, according to a study led by Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers who examined the Yanomami, a South American tribe living in near-total isolation. In fact, the tribe has researchers wondering what other so-called inevitable aspects of aging should now be called into question.

In a sense, studying the Yanomami allows us to go back in time. The group's members live in the rainforests and mountains of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, and their way of life has remained relatively unchanged for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. They're primarily hunter-gatherers who also garden. The Yanomami diet, low in fat and salt and high in fiber, consists of such items as plantains, cassavas (a root vegetable), fruit, and meat—mostly fish and the piglike mammals tapir and peccary. To flavor their dishes, they use hot peppers but no additional salt or spices. They get water from a stream.

Image caption: A Yanomami child wanders along the outside of a traditional tribal dwelling

Image credit: Courtesy of Noel Mueller

Owing to their isolation and the absence of Western dietary influences, the tribe has been an ideal cohort to study and assess the impact of a modern-world lifestyle. Studies of adult Yanomami since the 1980s have shown that atherosclerosis and obesity are virtually unknown among them, and that they have low blood pressure on average. For the new study, researchers wanted to use data collected by Venezuelan colleagues to determine whether the blood pressure of the Yanomami remained low over the course of their life span.

For the cross-sectional study, the team took blood pressure readings from 72 random Yanomami, ages 1 to 60. They also measured blood pressure in 83 members of the nearby Yekwana tribe, which is more exposed to Western influences, including some processed foods and salt. The researchers found that the Yanomami showed no discernible trend toward higher, or lower, blood pressure as the participants aged. In fact, their BPs remained remarkably consistent, and healthily low, throughout their life. (Notably, the levels have remained steady since the 1980s.) In comparison, the nearby tribe showed higher blood pressure levels beginning in early life.

In the United States and most other countries, blood pressure rises with age, beginning in childhood. High blood pressure is the leading indicator of premature death and, if untreated, can eventually cause heart disease, kidney failure, and stroke.

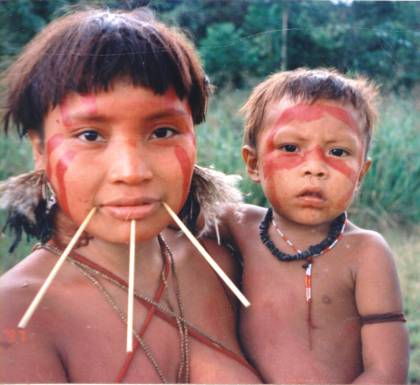

Image caption: A Yanomami woman and child

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

"That blood pressure increases as you age has been a widely held belief in cardiology for quite some time," says Noel Mueller, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Bloomberg School and one of the study's lead authors.

Results of this study, which appeared in the journal JAMA Cardiology, support evidence that blood pressure's rising with age is not a natural part of aging and could instead result from a cumulative effect of exposure to a Western diet and lifestyle. "So, it's not a universal phenomenon," Mueller says.

Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, consume on average 3,500 mg of sodium per day. (The Yanomami take in less than an estimated 100 mg/ day.) High sodium intake through Western world staples—pizza, breads, soups, cured meat, and most processed foods—increases the osmotic pressure of the bloodstream, which over time can lead to a thickening of the arteries that supply blood to the different organs, raising blood pressure. There's also a theory that an inevitable part of aging involves biological changes, some at the cellular level, which precipitate a gradual rise in blood pressure.

But low BP is not the only benefit of the Yanomami diet. In previous studies, researchers found that the tribe members also have an extremely diverse gut microbiome, which is known to build up immunity against diseases. But if you're thinking the Yanomami lifestyle is your path to good health and longevity, not so fast. The diet would be impractical for most in the Western world to replicate. Mueller knows. He tried to follow their diet for a 10-day period while he was down there. "I found it extremely difficult," he says. "I had to get used to eating this sort of cassava porridge, for one. And then I couldn't have any caffeine or soda, no stimulants of any kind." Mueller says he went through withdrawals, and his stool turned yellow, possibly the byproduct of a diet high in fiber and low in fat. However, at the end of his trial, he felt energetic and had lost some weight.

Mueller says we can take some cues from the Yanomami, like reducing our intake of sodium by 50 percent. He suggests following the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet—which focuses on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean meats—to help reduce sodium intake and lower cardiovascular disease risk.

Mueller and his colleagues plan to follow up with a study of the gut bacteria of the Yanomami and Yekwana to determine whether the gut microbiome accounts for the tribes' differences in blood pressure with advancing age. After that, Johns Hopkins researchers and colleagues in Venezuela want to begin a long-term longitudinal study, with the tribe's permission and continued support, to learn more about the impact—perhaps fewer instances of cancer, cognitive decline, and vascular aging—of isolation from Western influence. Until those results come in, maybe don't pass the salt.

Posted in Health