Mailman Robert Joyce was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan back when baseball die-hards were a special breed. Wins meant more, losses cut deeper, bad-mouthing the boys an insult to family.

Joyce understood that. In 1938, he got in a fight with two guys over the Dodgers after downing 18 beers at a bar. He left, got a gun, came back, and shot them. A press photographer snapped a photo of Joyce sitting at a table next to a cop shortly thereafter. A Dodgers fan who squeezed off a few rounds isn't that historically noteworthy, but this photo was taken by Weegee, the cameraman whose indelible work practically defined New York City tabloid imagery in the 1930s and '40s. His shockingly candid photos shaped what we think about when we think about the news.

"The picture's of [Joyce] sitting at a table completely wild-eyed," says veteran New York magazine city editor Christopher Bonanos, who came across Joyce while researching his new book, Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous (Henry Holt & Co.). "He has no idea what's just happened to him. And he's sitting handcuffed to a cop who is giving him side-eye like you can't believe."

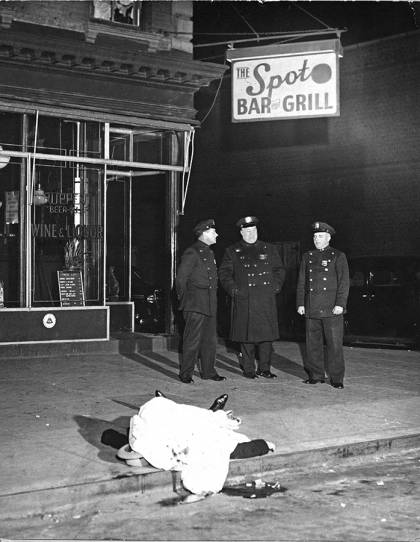

Image caption: Photographer Weegee was known for his provocative images of crime scenes.

Image credit: International Center of Photography

If you imagine a news photo of a murder scene, car crash, burning building, or perp walk from NYC's hardscrabble years between the wars, there's a good chance it's a Weegee. In Flash, Bonanos, A&S '90, charts how Weegee developed his gift for catching such momentary slices of life in response to violence. The freelancer tooled around the city in a Chevrolet coupe, its trunk overstuffed with film flashbulbs, spare camera gear, a change of shoes, even a typewriter he could use to bang out witty captions in the field. He was a nightcrawler who lived in a one-room apartment across the street from police headquarters, listening to his police radio to get the jump on the location of the next shooting, accident, and fire alarm.

"His knack for storytelling in a single frame is really unparalleled," Bonanos says.

In the mornings, Weegee'd sell his images to any of the city's nine daily papers, especially the afternoon tabloids that working stiffs read after clocking out. Weegee understood those folks. He was one of them.

He grew up in the Lower East Side and Brooklyn after arriving in New York in 1909 with his Jewish family, who emigrated from a small village now located in Ukraine. Born Usher Fellig, he became Arthur in America, a striver who found his calling when a neighborhood tintype portraitist took his photo around 1913. He tried that hustle—photograph a kid, ask the parents if they want to buy it—before scoring a darkroom assistant job at The New York Times and, then, at a photo agency. On-the-spot news didn't regularly appear in newspapers until the Daily News, "New York's Picture Newspaper," debuted in 1919. By the early 1930s, the city's newspapers were competing with each other for both the best stories and pictures. In the darkroom, Weegee learned how to work fast, picking up skills that led to occasional photo assignments.

He started freelancing full time in 1935, working the overnight beat, and never looked back, earning a reputation for getting more striking shots than his peers. He fought to get credited for his work—if photographers were credited at all, the line might say staff or the agency's name—eventually having a stamp made that signed all his prints "Weegee the Famous."

Anecdotally, the pseudonym was attributed to his ability to show up at murder scenes before anybody else, as if he had a Ouija board's uncanny gift. Bonanos suggests it probably came from his time in the darkroom as a "squeegee boy" who dries the prints. Weegee the Famous became one of the first name-recognized press photographers, publishing a book of his images in 1945 called Naked City. He wasn't the only cigar-chomping, fast-quipping hustler in a fedora with a Speed Graphic camera who gave photographers the reputation for being ambulance chasers, but he crafted that image into a signature, becoming one of the first news photographers to be taken seriously in the fine-art world.

"He understood what we now call personal branding before that word existed," Bonanos says. "He had that 21st-century impulse—he wanted to be famous. I joke that were he around today, he'd be pitching a reality show called something like I Shoot by Night or Murder Is My Business."

Bonanos started covering NYC as a reporter in the early 1990s. And while much about media has changed since Weegee's era, reporting hones the eye and ear to recognize what news looks and sounds like. "I often know what he was looking for in a picture in terms of news value," Bonanos says. "I've talked to art historians who study Weegee's photographs, and they come at them in a different way. What they see is valuable to me because I don't look at the pictures that way. They often look at them as photographic texts, a completely different view of the world. But they in turn don't look at them as news artifacts."

Video credit: Vulture

Flash impressively situates Weegee among the generation of journalists who profoundly shaped what city life looked like over the entire 20th century. His era of press photographers covered actual criminal underworld murders and police investigations at a time when hardboiled fiction was taking shape in pulp magazines, anticipating the high-contrast, black-and-white imagery of the B-movies of film noir. After making a tabloid name for himself, Weegee was hired by papers and magazines to turn his keen eye toward uptown social life, his eye-grabbing shots of swells' party life anticipating the decadent photoblogging of Mark "The Cobrasnake" Hunter and Last Night's Party's Merlin Bronques. By the time Weegee died in 1968, he had accumulated a massive record of 20th-century New York street life—some 20,000 original prints and negatives, tear sheets, manuscripts, correspondence, and personal memorabilia—that was donated to the International Center of Photography in 1993.

In 2012 Bonanos, a photographer himself, caught a Weegee retrospective at the ICP. By 2015, he was heading to the ICP on Saturdays to sift through the Weegee archive—which didn't, however, contain the photo featuring the homicidal Dodgers fan. Bonanos found that one himself, in the archives of the New York Post.

"I'm proud of this one in particular because it was an undiscovered Weegee photograph," he says, noting that in the many Weegee essays written and exhibitions mounted over the years, the image of the unfortunate Robert Joyce was never remarked upon or included, hiding in the Post's archives waiting to be found. "I managed to track down an actual print of it. It's framed next to my desk. This guy watched me as I finished the book."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged photography, journalism