James Wharton, A&S '20, was quite the curiosity in Virginia's Northern Neck region in the 1930s. Tramping around the isolated finger of land on the Chesapeake Bay, Wharton carried his handheld 16 mm movie camera wherever he went. And seeing someone walk around with a movie camera at that time—during the Great Depression and only a few years after the invention of documentary film—was akin to having a Hollywood filmmaker in town. A 1934 edition of the Rappahannock Record of Kilmarnock, Virginia, noted that a "great deal of interest is being aroused" over Wharton's filming. Another article in that newspaper said the local Future Farmers of Virginia chapter spent $200 on Wharton's filming of a school's agricultural activities, the equivalent of $3,700 today, but "public interest has amply justified the undertaking."

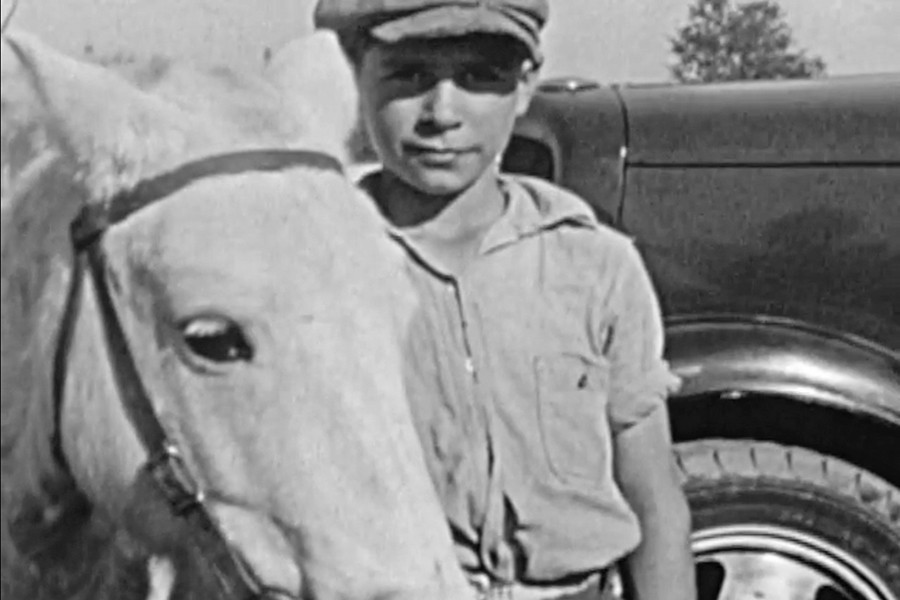

All along the region's rivers, streams, towns, and rural outposts, Wharton documented the lives of his friends, neighbors, acquaintances, and even complete strangers: workers skinning and packing tomatoes in creekside canneries; lithe young men skinny-dipping in a secluded Chesapeake Bay creek; oystermen plying the bay; and May Day festivalgoers dancing in elaborate costumes. Wharton even filmed footage of African-Americans playing baseball, a rarity in the Jim Crow era. His audiotapes include recordings of songs by African-American menhaden fishermen and Charles Henry Barnett, a black stevedore who passed the evenings on his porch playing a washtub and belting out tunes.

"I now see ghosts everywhere I go," says Northern Neck resident Bill Chapman, who is part of a local group preserving and showcasing the films. "I can't drive by the old, vacant White Stone School without seeing kids pouring out its front doors for field day. On Main Street in Kilmarnock, I see an old man leading a cow down the street, a dapper men's clothing store, and the huge Hazel Building that burned down long before I was born. And [yet] as much as I see the ghosts of another time, I see many things that haven't changed: watermen and their pound nets, oyster houses that are coming back, and community—people coming together to have fun."

Wharton's moldering trove of films and audio recordings, made from 1927 to 1938, was found in rusty tins beneath a guest room bed by Northern Neck resident Joni Carter, who was helping clean out the home of a friend's deceased mother in April 2015. She estimates the films had been there for 50 years. At the time of the discovery, Carter was among a group making a PBS documentary called Journey on the Chesapeake. She had known Wharton before he died in 1992—she remembers him writing a poem for her and reading it at her rehearsal dinner. She scoured Craigslist and eBay for a 16 mm projector. "Finally, I found the right projector and was able to watch the films, and within minutes I knew the value of the treasure I had found," Carter says. "I couldn't take my eyes away until I had watched each one."

Carter and a friend recruited Chapman to launch the Wharton Films Project to preserve Wharton's movies and audio recordings and turn them into a documentary. Chapman created a Facebook page for the project, seeking volunteers to help log the films and identify as many settings and people as possible. Meanwhile, the Library of Congress is cleaning and digitizing the films at its digitization facility in Culpeper, Virginia. In exchange for their help, Carter says, Wharton's movies will be donated to the library after the documentary is completed.

The films have already been showcased locally at the Rappahannock Art League in Kilmarnock and the Mary Ball Washington Museum and Library in Lancaster, Virginia. The older generation, some of whom have parents and kin in the films, found them mesmerizing, Carter says. "Imagine seeing your deceased mother at 16 years old, dancing a jig in a high school show, or your father at 20, showing off his physical strength for the camera by juggling huge logs," Carter says. "Many who watched the film were in tears."

Carter says Wharton had a deep connection to the region, and these films were his gift to the community. He was the son of an evangelical Baptist preacher whose tent revival meetings drew thousands to a leafy camp on the banks of the Corrotoman River. Young James played piano for his father's hymns, and the site was transformed into Wharton Grove, a Christian camp and retreat center. After high school, Wharton attended Johns Hopkins, where he took courses in English composition, English literature, and French. He went on to take a litany of short-lived jobs, including as a proofreader for The Baltimore Sun, a gig that Carter thinks may have been where Wharton got his movie camera.

Wharton took over Wharton Grove, which had become a summer resort, when his father died in 1928. He wrote books, contributed articles to historical quarterlies, and played piano for silent films in the local theater, all the while toting around his 16 mm movie camera. He screened his films in local movie theaters and schools for a dime or quarter per person.

Chapman says people often view an earlier time as the "good ol' days." Wharton had a different perspective. He "seems to have looked around him and said, 'These, right now, are the good days,'" Chapman says. "And he set out to capture everything that he found interesting and special about the place where he lived and the people he lived with. There's so much love and pride in every frame."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged documentary, american history