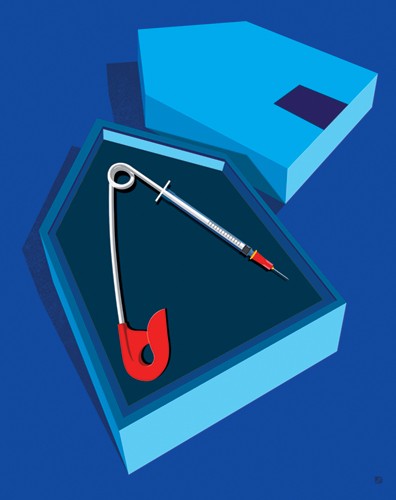

The typical morning scene at Insite has clients lined up outside this building with a boutique-store facade. Once inside, they sign in, wait, and then are politely escorted to a mirrored, light-filled booth where music gently plays. There, they can inject heroin. Located in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighborhood—an area of the Canadian city notorious for its drug trade, poverty, and crime—Insite is North America's first supervised drug-injection center. For a certain fragile population, the site offers sanctuary.

Image credit: Paul Garland

Hundreds visit the facility daily, some more than once, to safely inject illegal drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and morphine at one of 13 booths. Clients are provided sterile supplies to use their own drugs under the watchful eye of trained medical staff, without fear of prosecution. This is a no-judgment zone. Nurses stand by to treat infections, change dressings, and offer immunizations for the flu, hepatitis, and pneumonia. If asked, caseworkers connect people to addiction counseling and a residential treatment program upstairs. They can also provide referrals to affordable housing and career counselors.

Since Insite opened in 2003, more than 75,000 people have come here to inject. That amounts to 3.6 million total injections that otherwise might have occurred unmonitored in a back alley, city park, restaurant bathroom, or abandoned house. According to Vancouver Coastal Health, the region's health authority, Insite staff have to date performed more than 6,400 overdose interventions, with no deaths at the site. The site has also helped reduce the high-risk behavior associated with HIV transmission, such as the sharing of dirty needles and unprotected sex.

No such facility currently operates in the United States, but a new cost-benefit analysis conducted by the Bloomberg School of Public Health and published in the May 2017 issue of Harm Reduction Journal, suggests that a single safe consumption space in Baltimore would annually prevent 5 percent of overdose deaths and save $6 million in costs related to the opioid epidemic. Drug overdoses now account for more fatalities than gun homicides and car crashes, and the problem is getting worse. The number of overdose deaths has climbed because of cheap and increasingly available synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin or morphine, says Susan Sherman, a professor in the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Bloomberg School and senior author of the study.

She says doors are often closed to drug users. People who need more support are given less. "These [supervised injection] spaces increase the touch point we have with this population," Sherman says. "They're connected with people who can keep them safe and offer help. With drug users, you first have to stabilize your life before you can make positive change."

New strategies to reverse these trends are needed, she says, because the criminalization of drug use—the so-called war on drugs—has not worked. According to the nonprofit Drug Policy Alliance, more than 1.5 million drug-related arrests are made every year, the overwhelming majority for possession only. A recent report from a team of researchers from the Bloomberg School and the University of British Columbia suggests that drug criminalization has a negative effect on HIV prevention and treatment among people who inject drugs. The researchers found that stiff penalties for possession of illegal drugs have failed to reduce drug use. "You can't arrest your way out of the problem," says Sherman, a co-author of the report. "The war on drugs was not won. It's a large-scale example of a failed social, economic, and health policy with huge implications on all of these fronts. There are a disproportionate number of African-American males in jails and prisons. You basically take a considerable proportion of a racial and gender group out of society, which has a substantial direct and indirect impact on the social fabric of a neighborhood and in communities at large."

Sherman says we need to look for alternative policies to limit the harm of drug use, including more needle exchanges and either supervised injection sites such as Insite or supervised consumption spaces, which allow clients to snort, smoke, or ingest drugs. There are more than 100 supervised consumption spaces in 66 cities and 11 countries. The first government-sanctioned consumption room opened in Bern, Switzerland, in 1986. Health care workers there realized that drug users often congregated in cafes and went into the bathroom to inject. Why not open a cafe where they could do so safely under supervision? The most successful programs, Sherman says, feature low thresholds for entry, meaning provided you're not rude or violent, or try to share or sell drugs, you can have a seat.

Natanya Robinowitz, SPH '12 (MPH), a harm reduction specialist who was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to study safe consumption spaces in Spain, says resistance to such sites often falls into the category of NIMBY-ism, or a belief that such a facility would condone and promote drug use. With such a perception, Robinowitz says it's important to convince elected officials and law enforcement that such sites are foremost interventions. "If condemning drug use and criminalizing drug users were effective, we wouldn't have any heroin in Baltimore City. This is a way to build trust and create relationships over time by treating people with dignity and respect," she says. In a 2017 New England Journal of Medicine opinion piece, the author notes several studies of European sites that have shown an increase in visitors initiating treatment for substance use disorders, without an increase in drug trafficking or crime in the surrounding area. At Insite, there's been only one known case where someone did their first injection in the space.

There are campaigns underway to open supervised consumption spaces in Seattle, San Francisco, Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore. Those plans may run head-on into U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, however, who has publicly advocated tougher penalties for drug violations. But Sherman is confident a safe consumption space will open in the U.S. in the next three to four years, if not sooner. "There is traction in these cities. There's evidence they work."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged heroin, drug abuse, drug treatment centers