When S. Frederick Starr informed his father in the early 1990s that he was going to buy a rundown plantation house in the middle of New Orleans' Upper Ninth Ward, his father told him he was insane. "At that point, the neighborhood was cocaine central," says Starr, chair of the Central Asia–Caucasus Institute at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. "The house had a 12-foot cyclone fence around it, a row of scrub trees, and a concrete biker bar in the front yard. I could see drug deals going on from the kitchen window."

But Starr, who had written a book on the city's Garden District after serving as provost at Tulane University, recognized that this house, known as the Lombard Plantation after the family that had built it in 1826, was an architectural treasure. "It's really this rare thing—a totally intact rural West Indian plantation house sitting right in the middle of the city," he says. "By the 20th century, the people owning the house were too poor to mess it up. Essentially, poverty saved what prosperity might have destroyed."

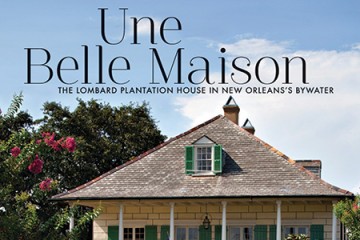

Starr ended up purchasing the house with a partner for $109,000 and began the long process of restoring it to its 19th-century grandeur. Now Starr has published Une Belle Maison: The Lombard Plantation House in New Orleans's Bywater (University Press of Mississippi), a history of the property and its 12-year restoration.

The plantation house is not of the opulent Gone with the Wind variety but a far more modest Creole-style structure, with four large first-floor rooms, a sprawling Norman-trussed attic (one of the best examples in North America, according to architecture historians), and a simply columned front porch, all typical of the era and region in which it was built. It remains one of the last surviving—and most complete—of the many grand homes that once lined the Mississippi downriver from the French Quarter.

According to Starr's book, an 1835 bill of sale described it as "une belle maison," and the property served as a working farm throughout the 1800s, first for growing sugar cane and then vegetables and hemp, to be turned into rope at the nearby shipyards. But by the 20th century, the city expanded downriver as "shotgun" houses were built to accommodate the growing population. By the mid-20th century, with the area sinking into poverty, the building was divided into apartments.

When Starr acquired it, its exterior was a mess, but inside, all the original woodwork, doors, hinges, and floors had been preserved. "Everything was there," says Starr, who later purchased his partner's share of the home. "It had been totally neglected for a century."

Eventually, Starr, who flew frequently to New Orleans from his home in Washington, D.C., to oversee the restoration, was able to buy—and demolish—the biker bar as well as a shotgun shack that had occupied the plantation's rear yard since the 1930s. Thanks to the city's old notarial system that required copious documentation whenever a property changed hands, Starr was able to re-create a surprising number of interior and exterior details, right down to the Italian yews replanted in the exact spots depicted on a painting from an 1844 property sale.

Amazingly, the house lost only a couple of roof slates during Hurricane Katrina—credit the original builders, who sited the property on higher ground than the rest of the area. Since the storm, Starr says, the surrounding Upper Ninth Ward neighborhood, also known as Bywater, has improved markedly, and he often greets passersby who knock on his front door, curious about the anachronism.

Une Belle Maison is Starr's fifth book about New Orleans, a city the Cincinnati native grew to love as a teenager while traveling as a musician on riverboats along the Mississippi. Starr still tours as a clarinetist with the Louisiana Repertory Jazz Ensemble, a nine-piece band that specializes in pre-1930s New Orleans jazz and has released a half dozen albums. "We're playing a lost repertoire, bringing back from oblivion bands that were totally forgotten from that era," he says. While at Tulane, he also founded the Greater New Orleans Foundation, which has grown into one of the region's largest philanthropic organizations.

This fall, he publishes another book as well, a major scholarly work called Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane (Princeton University Press), the largely untold history of Central Asia's intellectual awakening during the Middle Ages. But for Starr, the restoration of the Lombard Plantation and resulting book are clearly labors of love. "I don't play tennis," he says of his outside pursuits. "[The Une Belle book] is something I've done with my left hand."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged history, architecture