Credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

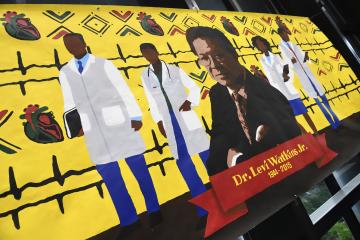

Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories named in honor of Florence Bascom

The Homewood campus building was dedicated Oct. 12 to recognize Bascom, a trailblazing figure in Earth science, geology, and education

By Hub staff report

/ Published Oct 17, 2023A vital Homewood campus building designed to foster undergraduate research has been dedicated to honor geologist Florence Bascom, the first woman to earn a PhD from Johns Hopkins University.

Students, faculty, and university leadership gathered Oct. 12 to celebrate the newly named Bascom Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories, a change that immortalizes Bascom, who earned her PhD from Hopkins in 1893. Bascom was a pathbreaking figure in Hopkins history who made it part of her academic mission to encourage young people—especially young women—to establish themselves as the next generation in her beloved field, said JHU President Ron Daniels in his remarks during the ceremony.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"All of us, myself included, have had at various points in our career people who have pushed us. Who have insisted on us aspiring to higher standards. Who have insisted that we actually do better and be better in the way in which we do our work, and to embrace the path that we've embarked upon no matter how difficult it may be," Daniels said. "Florence Bascom's legacy as an educator and a researcher will continue to live on, through countless students who use these labs, and the faculty and post-docs who teach in them. And Johns Hopkins University is truly thrilled, and proud, to be able to dedicate these laboratories in her honor."

The dedication of the Bascom Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories is part of the work of the Diverse Names and Narratives Project, an ongoing effort across the enterprise to more visibly honor and celebrate remarkable people from the institution's history, with a specific focus on those from historically marginalized and underrepresented groups.

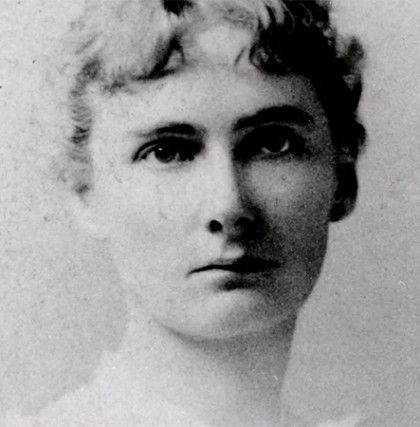

Image caption: Florence Bascom

The festivities on Oct. 12 included performances by the Sirens a capella group, as well as remarks by students Michaella Huertas, Em Ambrosius, and Anna Vakhnovetsky, and Christopher Celenza, dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. Celenza said it was fitting that the building now bears the name of a trailblazer such as Bascom because it's "a place where a lot of firsts happen"—the first place where many undergrads conduct research, where nascent theories are first formed and tested, where new methods are first put through their paces, and where interdisciplinary connections are first explored.

"As a doctoral student here, Dr. Bascom was required to sit behind a screen in the classroom to avoid 'disturbing' the male students," Celenza said. "It is my hope that we use today's occasion to remind ourselves to tear down every figurative screen we encounter, bringing all members of this community—along with all of their ideas, backgrounds, experiences, and points of view—into the full light of day and the full mix of rigorous collaboration and discussion that helps each of us—and our community as a whole—reach our fullest potential."

Long before she became a renowned figure in Earth science, geology, and education, Bascom applied to the PhD program in geology at Johns Hopkins, at a time when the university did not admit female students. A special exception was made for her, and she was granted admission on the basis of her extraordinary abilities and record. Undeterred by the customs and norms that isolated her from her male peers, Bascom became the first woman to earn a PhD from Johns Hopkins University, in 1893, and was just the second woman in U.S. history to earn a PhD in geology. She went on to become the first woman employed by the U.S. Geological Survey and also founded a leading academic center of geology, paving the way for generations of female geologists.

Image caption: Student speakers Michaella Huertas, Em Ambrosius, and Anna Vakhnovetsky

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

In 1895, Bascom founded the esteemed geology department at Bryn Mawr College, where she taught for 33 years. She helped establish the Bryn Mawr geology program as one of the nation's best; she also trained and mentored dozens of women who would go on to become leaders in the field.

"The fascination of any search after truth lies not in the attainment … but in the pursuit, where all the powers of the mind and character are brought into play and are absorbed in the task," Bascom said in remarks delivered upon her retirement from teaching in 1928. "One feels oneself in contact with something that is infinite and one finds a joy that is beyond expression in 'sounding the abyss of science' and the secrets of the infinite mind."

Bascom was born in 1862 in Williamstown, Massachusetts, the daughter of a Williams College professor and a suffragist teacher. She earned both Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees from the University of Wisconsin, where she also received a Master of Science in 1887. It was there that she discovered her love of geology, specifically the subfield of petrography, which involves the study and description of the layers and characteristics of rocks.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

At a time when most female geologists focused on analysis and drafting charts, Bascom actively engaged in field research, including the study of the rocks of the Piedmont region of Maryland and Pennsylvania, the work for which she became best known. Her doctoral work at Johns Hopkins explored the origins and formation of the Appalachian Mountains, and her thesis, published in 1896 by the U.S. Geological Survey, remains a foundational work of Appalachian geology. In 1919, she became the first professional woman geologist to survey Maine's Mount Desert Island, home to Acadia National Park. In all, she published more than 40 articles on genetic petrography, geomorphology, and gravels.

Bascom was the second woman elected to the Geological Society of America, in 1894, and was elected GSA vice president in 1930, making her the organization's first female officer. She was also a member of the United States National Research Council and the American Geophysical Union.

She worked as an assistant geologist for USGS and served as an associate editor of American Geologist magazine. In 1906, the first edition of American Men of Science rated her among the top 100 leading geologists in the country.

The USGS Florence Bascom Geoscience Center in Reston, Virginia, is named in honor of her legacy, as are an impact crater on Venus, an asteroid, and a postglacial lake.

Krieger School Dean Christopher Celenza

Credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University