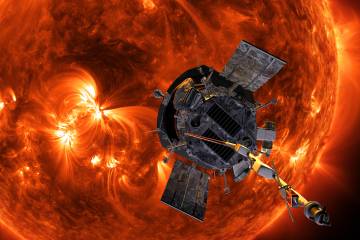

Geoff Brown likes to talk rocket science. And he likes it even better when media outlets are doing the talking. As public affairs officer for the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Brown helps lead the messaging effort of the Lab's Civil Space program, which supports NASA through space science, spacecraft design and fabrication, and mission operations. Brown, who joined APL in 2012, has worked on several missions, including NASA's Van Allen Probes and the New Horizons 2015 Pluto flyby. Of late, his working hours have been consumed by NASA and APL's daring project to touch the sun. On the early morning of Aug. 12, the APL-built Parker Solar Probe launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida aboard a Delta IV Heavy rocket. During the next seven years the spacecraft will orbit the sun 24 times and come within 4 million miles of the celestial body to gather data on the processes that heat the corona and accelerate the solar wind. Just weeks after the launch, we sat down with Brown over coffee to talk about what it's like working with the Lab's scientists, engineers, and analysts who both safeguard our nation's security and advance the frontiers of space. Spoiler alert: No classified secrets were divulged.

You're a JHU alum, class of 1991, with a degree in international studies. What was the plan out of college?

In international studies, you have to write a lot. And I eventually realized I liked writing papers perhaps more than the prospect of studying one or two particular areas for the next 50 years. So that's when I migrated out of political science and more into magazine writing. I went, Oh, this is what I like to do—write big complicated stories. I guess I brought the research aspect I learned at Johns Hopkins into these stories.

You worked for Baltimore magazine and an NPR affiliate in addition to your freelance work. Did you seek out stories in science and technology early on in your career?

Yes. I thought everyone wanted to write about science and technology, and I was going to have to fight for it. And I found out that not so many people want to, or can do it well. [Science writing] turned into a sort of niche for me, and I wound up writing for a lot of Johns Hopkins publications before the job at APL opened up. Several people told me this would be a good fit for me, and they were right.

What was that transition like, coming from the realm of journalism and magazine writing to a place like APL?

At APL, I think we give people an ample amount of time to figure it out, as it's a unique, big place that has its own way of doing things. Even people who come from similar companies and organizations have to adjust. This is the biggest place I ever worked. We're at like 6,300-plus people now. We have 453 acres here in Laurel, Maryland. The job I do now is not the job I started with. For one, the media landscape has changed. When I got to APL, it was more traditional PR—write press releases and pitch media. We didn't even have a social media person. But in the last three years, it's changed a great deal. Now I script and produce videos to help get our message out. I don't write as much. I more direct teams to do stuff, and at APL we have a lot of stuff going on.

For a project like the Parker Solar Probe, which was literally built at APL, how do you go about learning all you need to know about the science and engineering aspects? Do you sit down with the team and ask them: Tell me what that dohingy does?

A little bit of that. At APL, it is mostly engineers, but also some scientists. There are great aspects of working with both of them. For the engineers, if you show them you're interested and have done your homework, they are more than happy to show you how they solved this problem. The thing I like most of getting to know these folks is that some of these people have been working on an aspect of a project for decades. Their whole career is sort of intellectually invested in this thing, so they are really proud of it and love talking about it with people who are interested. And they want more people to know about this really cool thing they've worked on or discovered. They were given a problem, and they managed to solve it or fix it. Sometimes it's a very specific question or problem. Like make something survive a trip around the sun.

Give me one "holy smokes" moment when talking with the engineers and scientists who worked on the Parker Probe.

I'll go back to the question I just laid out: Design a spacecraft that will survive a trip around the sun. It takes three huge technological jumps to make that happen, and they sort of just worked it out. First, you need a heat shield, and now there's carbon technology that will make it light enough that we can do that. But we can't test it at full size as there is no vacuum chamber on the planet that we can make hot enough that you can test an 8-foot thermal shield. So, we'll have to find a way to test a little piece of it. All these things would be daunting to "regular" people. We needed to design a cooling system for the solar arrays as they would get too hot. We had to build an autonomy system for the spacecraft to protect itself, as there are long periods of time that we can't talk with it. It's the totality of it. Every one thing is amazing, but it's the bridge we built to the other amazing things that makes it all possible.

You mentioned prior to this interview that you were just now catching up on sleep. What exactly was keeping you up?

Leading up to the launch we had a slew of documentary crews to work with and global media requests. There were about 180 registered media at the press site and Kennedy for the launch on first night. But we also had to handle the launch itself, which happened at 3 a.m. The people working on the project kind of sleep shift to get used to the timing. Regularity just goes away. Everyone is amped up, and adrenaline gets you through all this. But after two weeks of it, you're like, I should probably get some sleep. APL has a major launch every five years on average. They are not rare, but there's a lot of work that goes around each one.

How many media "hits" does something like the Parker Probe generate?

We were doing about three or four interviews a day for about the past three weeks. We just had a constant deluge of requests. We did the mission for NASA, but since we built and designed it, it was primarily APL folks doing the talking. We were fielding requests from across the globe—we have team members who speak Spanish, Japanese, Italian, French, and some other languages. We did a little metrics review, and that was on just over 2,000 stories, but there were lots more.

For your part, is there a lot of yes, sure, or does there come a time when you have to say no to a media request?

A lot of people asked us if they could come down to APL and film something. But we had to tell them that not everything is filmable anymore because [the spacecraft] had gone to Florida. We do have a couple of spare thermal shields, so people could come and shoot those. Everything is basically yes because it's NASA and it's open to the public, and people wanted information on how this spacecraft, and the science, works.

Oddest media request you said yes to?

Maybe one thing we did for a BBC show, and it was my suggestion. When building Parker, we used Microsoft HoloLens and other AR [augmented reality] technology to build a virtual spacecraft. People could telecon in or just interact around air to virtually walk around this spacecraft that we're working on. When this BBC crew asked us if they could film the spacecraft, we had to say no, as it was in Florida, but we have this AR thing, let's do it that way. It was tricky to do technically, but we pulled it off. Everyone wore the Microsoft headsets, and the BBC crew filmed the interviews with people essentially looking at air, although what they were really looking at was the virtual spacecraft. Later they could edit the viewpoints together, so the viewer could see what the people with headsets were seeing at a particular time. It worked, and it was really neat.

Tell me what it's like on launch day—the hours and then minutes leading up to the launch.

We had the first launch attempt on Saturday, Aug. 11, and we got really close but couldn't launch because a couple of relatively small things got in the way and we had to reschedule. The actual launch day is very white knuckle, and people are extremely amped up and ready to go because many have been working on this project forever. There's a little bit of euphoria because this thing they've been working on for years is about to happen. But there's also a little bit of, "and be safe out there," as we are sending this spacecraft to a really dangerous place. Once you see it take off successfully, you just marvel at how good everyone is at their jobs. This is a custom-built spacecraft that we made from scratch. The project manager estimated that 4 million hours went into building this thing. It's a mission with a lot of heritage. Thousands of people worked to get this spacecraft launched. The dream is finally real. There is a lot of emotion there.

Where are you during this?

We're at a press site at Kennedy, about six miles from the launch pad. Right at launch, everyone runs outside. There are some old TV structures, roughly two or three stories tall, that you can go up on to get a better view. Then you head back inside because it's Florida in August and it's still 85 degrees at 3:30 a.m.

What's it like in there?

About 45 minutes after launch, control of the spacecraft is turned over to APL. That room is packed. It's our newest MOC, or mission operations center. Everyone waits around anxiously and then goes, OK, time to go to work. We ask, Where is [the spacecraft] pointing? as you want to make sure it's on the best trajectory.

If the media faucet was on full blast a few weeks ago, where are we now, a drip?

It has really tailed off. But we're going to put out another update today, as we just completed a trajectory adjustment and may not have to do another one. We're within .2 percent of our optimal trajectory, which is great. We'll go to Venus in four weeks, and six weeks after that we reach the sun. Then the craft will rotate around the sun 23 more times, getting closer and closer each time.

If you weren't one before, how much of a space geek have you become?

I was always into space science, so it's really exciting to be working on these projects. Everyone here is a convert after a while. Our scientists and engineers are so great at this stuff, so it's great to be part of the team that is helping the world find out about the universe. You quickly appreciate how hard they work, and how hard the science is. I knew it was hard before, but honestly, it's a thousand times harder than you could imagine. For example, I didn't realize just how hard it is to get to the sun. The Earth is moving some 67,000 miles per hour in space, so you basically have to jump off the Earth and get rid of all that momentum because the spacecraft is going the wrong way. We have to get it headed in the right direction, and that is why we used the biggest rocket NASA had to counteract the forces that pulled us one way. Relatively speaking, it's way easier to get to Mars.

I'm rewatching the James Bond movies with my older daughter…

Moonraker is not real.

Ha. Close to what I wanted to ask. I'm watching all the Q Branch sequences, where Bond is handed his new field gadgets. Is there any touch of that at APL, where you are trying out fantastical gadgets and devices that push the boundaries of what is possible?

The space work that we do is just roughly 20 to 25 percent of the Lab's work. We have folks working on everything from materials testing to undersea research to anti-missile systems. Right now, we have people working on transparent armor, a sort of bulletproof glass. We have people working on protecting soldiers from under-vehicle explosions. Our staff work with military folks in the field, hearing and seeing their problems firsthand and then helping them fix them. We're also working on DART, an asteroid deflection test. So, yes, there is a lot of gee whiz stuff going on.

Posted in News+Info

Tagged who does that?