- Name

- Jill Rosen

- jrosen@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9906

- Cell phone

- 443-547-8805

A 4.8-magnitude earthquake that hit New Jersey on Friday morning sent shivers through the Northeast, triggering a seismometer in the basement of Olin Hall on Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus. Surprised people across the region sensed the tremors, prompting Hopkins affiliates to ask each other, "Did you feel it?"

"It's unusual to get really big earthquakes in the Northeast of the U.S., but you do occasionally get these intermediate-size earthquakes, which is what we had this morning," Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences who studies seismology at Hopkins, says in an interview with Live Science.

Also see

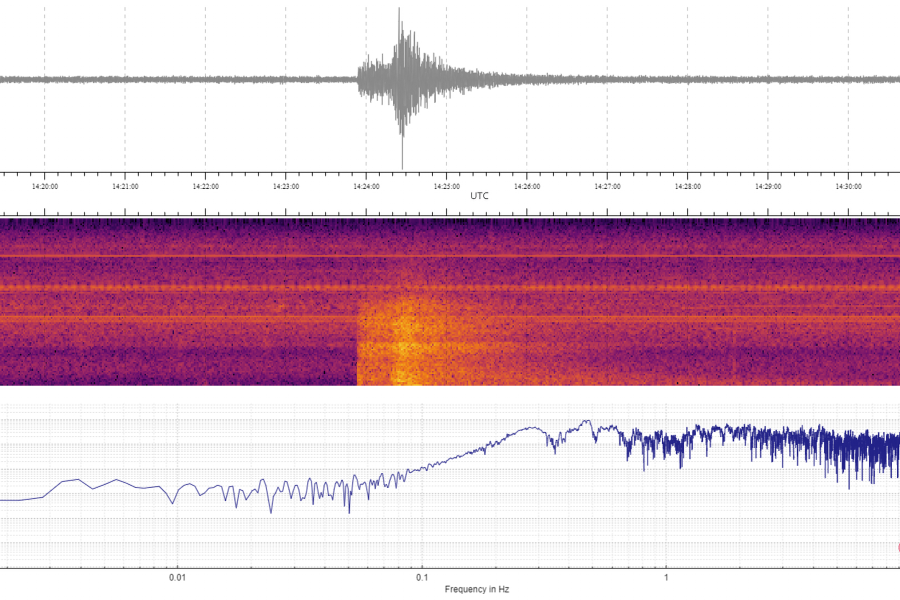

To help unpack the science behind the shake, Fernando shares the colorful image above, representing data from the Homewood seismometer's activity at 10:23 AM EDT April 5. He explains that the top plot shows the vertical ground velocity over time. The larger amplitudes around 14:24 UTC (Universal Time, which is four hours ahead of EDT) indicate high velocities when the earthquake reached Baltimore. The bottom plot also shows velocities, he says, but in what is known as a spectrogram, showing the frequencies, or different pitches, contained within the signal. The bright oranges and yellows indicate higher energies, and dark purples and pinks indicate lower energies, Fernando says.

"Different parts of the planet feel earthquakes with different severities and different frequencies depending on the geological setting and how close they are to other features like subduction zones," Fernando tells Gizmodo. "The northeast of the U.S. tends to be pretty quiet, so events like this are quite rare. Certainly not something you see every year, or maybe even necessarily every 10 years."

Additional earthquake facts from Fernando:

- Most earthquakes occur where two tectonic plates meet, such as along the San Andreas Fault in California or the Cascadia Subduction Zone in the Pacific Northwest.

- The East Coast of North America does not have any active plate boundaries anymore but does contain the remains of ancient ones.

- The formation and breakup of the supercontinent Pangea and the opening of the Atlantic Ocean hundreds of millions of years ago left deep fractures and faults in the bedrock.

- These faults can reactivate for a variety of reasons, including the crust readjusting to changes in pressure or reactions to far-distant tectonic forces.

- Tectonic stresses on these faults are much smaller than on faults along the West Coast of the U.S., so earthquakes on the eastern seaboard are generally much smaller and much rarer.

- The epicenter of the earthquake was within the Ramapo Seismic Zone (RSZ), which runs through northern New Jersey (Wheeler, 2006; Sykes et al, 2008).

- The RSZ was highly active during the Triassic period, roughly 200 million years ago, and is associated with the formation of the Atlantic ocean and the breakup of Pangea. A series of similar faults run down the eastern side of the Appalachians from Nova Scotia to South Carolina.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged earth and planetary sciences, earthquakes, krieger school