At first, Tonika Berkley was mystified by the markings she found on the sheet music that once belonged to Ethel Ennis, the Baltimore-based international jazz musician. They marched across the page where lyrics would go on a sheet of music, but they looked more like horizontal lines with squiggles at the end.

Then, as the Africana archivist for the Sheridan Libraries and the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts pored over some of Ennis's papers from her studies at business school, she recognized the same marks and realized they were shorthand. Ennis had blended her B-School skills with her musical ones to create a resource tailor-made for herself.

"Most of the piano and vocal sheets feature Ennis's handwritten notations, abbreviated using stenography notes so that she could remember her lyrics easier," Berkley said.

Ennis and her husband—author and journalist Earl Arnett—kept everything. Which meant that, as Berkley organized the material the couple had passed along to Johns Hopkins' Sheridan Libraries in 2018, she was not only able to make the connection about Ennis' lyrics, but she and her colleagues had plenty to work with as they pieced together Ennis' life in Baltimore, in jazz, and in the global community. Ennis died in 2019. Arnett continues to live in the Greater Mondawmin home the couple shared for 52 years.

"I feel truly honored to be working with this collection as an archivist, as a Black woman, as a lifelong fan of jazz music and Baltimore history," said Berkley, who remembers watching Ennis portray the Ethel Earphone character on Maryland Public Television's Book, Look, and Listen program as a kindergartner.

View this post on Instagram

The collection contains sheet music, recordings, and memorabilia from Ennis' long international career, including film and video recordings of some of her live and television appearances preserved by Arnett, said Gabrielle Dean, curator of rare books and manuscripts at the libraries. It also contains materials from her family and everyday life, including photographs, ephemera, and newspaper clippings.

"Some of these relate to her life growing up, but also politics, baseball, cooking—all the things she was interested in," Dean said. "It also documents Earl's career and interests—manuscripts from his days as a journalist for The Baltimore Sun, for example. And it includes business records from the various enterprises Ethel and Earl founded and ran together here in Baltimore, because they were committed to artistic livelihoods in the city."

It takes a lengthy and complex process to do justice to such a multifaceted collection and the exhibit it generates. Dean first heard in 2017 that Ennis and Arnett were interested in creating an archive that would be accessible to the public and that would stay in Baltimore. At first it appeared that a music library—like the Friedheim Library at the Peabody Institute—might offer the best fit. But when Dean and Friedheim Library archivist Matt Testa went to see the material at Ennis and Arnett's home, they realized it was also a local history collection.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"That's when we understood that we needed to think more imaginatively about this incredible collection and how to care for all of it," Dean said.

By 2018, the Sheridan Libraries had finalized a purchase agreement, and four library staffers packed up the collection over a couple of hot summer days. "Ethel was not well by that time, but she was very gracious and funny," Dean remembered.

Ennis died the following year, and the Sheridan Libraries held a memorial concert for her at the Peabody Institute. The adoring crowd that packed the venue was further inspiration for Dean and her colleagues to find a way to make the collection widely available.

In 2021, a Mellon Foundation grant called Inheritance Baltimore allowed the libraries, the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts, and what is now the Chloe Center for the Critical Study of Racism, Immigration, and Colonialism to hire the specialists whose expertise, care, and time would transform the collection "from 100 boxes on a shelf to something full of life, public, and newly generative," Dean said.

Tasked in 2021 with processing the archive and assisted by Jess Douglas and Xavier Walker, Community Archives fellows for Inheritance Baltimore, Berkley began categorizing and inventorying some 155 linear feet of materials, 474 audio files, 51 videos, and three film files. Now tagged and catalogued, the collection is stored at the Libraries Service Center in Laurel, Maryland, where it will be available to researchers beginning this spring.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"My first task was figuring out where to begin," Berkley remembered. Digitizing Ennis's recordings on obsolete media like VHS tapes, film and audio reels, and U-matic magnetic tape was an important step, she said, as the technology to play back such recordings is also becoming obsolete, and the materials themselves were at risk of deterioration. The team created a collection of 33 of these live performances and interviews on Aviary, an audio-visual web-based platform.

About a year later, Berkley was joined by Raynetta Wiggins-Jackson, curatorial fellow for Africana collections—another position made possible by the Inheritance Baltimore grant. The ethnomusicologist's role was to develop a theme and curate an exhibition of the materials, which opened in October and runs through April 14 at Hopkins' George Peabody Library in Mount Vernon.

With such an extensive trove of materials to work with, the exhibition could have taken any number of directions. But as Wiggins-Jackson got to know Ennis through her explorations of everything she and Arnett had saved, she quickly landed on two guiding principles: She wanted to highlight Ennis as a daughter of Baltimore, and she wanted the exhibit to reflect Ennis's voice.

"Throughout her travels, Ethel was outspoken about her roots and experiences growing up in Baltimore. Her connection to and pride in her hometown is apparent through so many of the materials in the Ennis/Arnett collection," Wiggins-Jackson said. "It was clear that life in Baltimore was a significant part of Ethel and Earl's story—and I thought it was important for the exhibition to honor that.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"We also saw this exhibition as a wonderful opportunity to share Ethel's story by putting her perspectives in the foreground," Wiggins-Jackson added. "There were speculations about why she chose to remain in Baltimore as well as her choices to walk away from major career opportunities. So we made it a priority to let Ethel speak for herself as much as possible. Rather than rely solely on the interpretations of onlookers, loved ones, and colleagues to narrate her story, we wanted to give space for Ethel's own words to clarify her thoughts about what she considered important in her life."

In addition to the exhibit, a series of related events have been designed to help the broader community tap into the archives and Ennis's legacy, specifically by introducing live performance into the exhibit space and others. Seeking connections within Baltimore and the jazz community, Wiggins-Jackson contacted Brinae Ali, lecturer in dance at the Peabody Institute. The result was an opening celebration featuring performances by vocalist and Peabody lecturer Charenée Wade accompanied by the Peabody Jazz Ensemble, and a birthday bash at Baltimore's Keystone Korner jazz club featuring Wade and the jazz ensemble along with jazz pianist, composer, and Baltimore native Cyrus Chestnut; the Baltimore School for the Arts Jazz Ensemble; and dance by Ali herself.

Co-curating events that draw from the well of an artist's legacy reimagined for a current generation has connected deeply with Ali's own work of understanding how music touches people the way it does. "We really understand the value of creating spaces for people to remember, to reflect, to release, and rejoice," she says of working with Wiggins-Jackson and Berkley. "And to find ancestors who did that, and you see the blueprint of their life and how they did it, it really is an honor."

Additional events are planned, including one on Wednesday, Feb. 21, at Baltimore's Creative Alliance and an exhibition closing event on Sunday, April 7, at the Peabody Library.

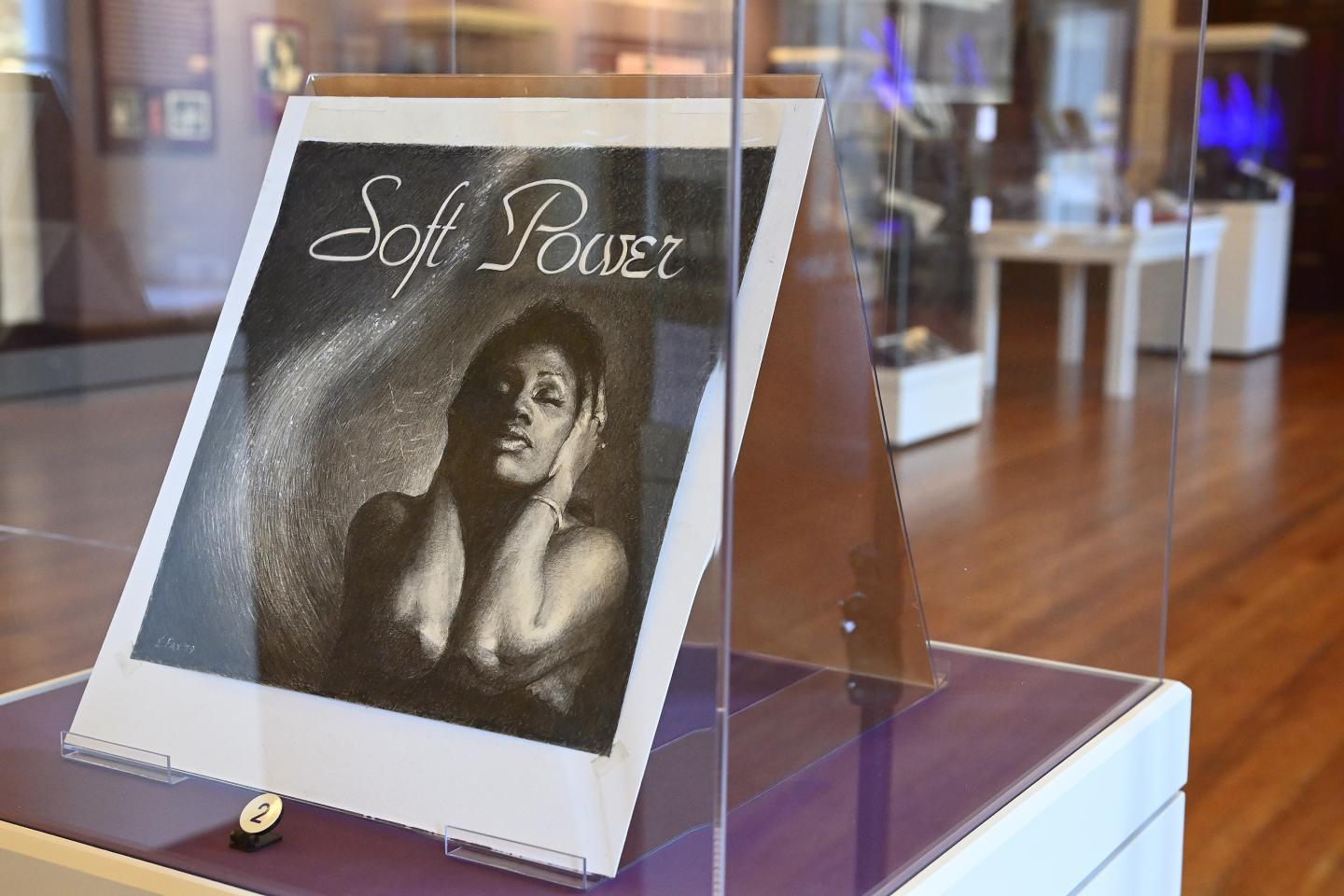

Ennis was known for her strong principles, refusing to follow the advice of her success-driven agents if it didn't feel true to herself. Early in her life, she defied her devoutly Methodist grandmother by entering the world of jazz, but Wiggins-Jackson says she always embraced her grandmother's warnings against letting other people—or their money—change her core. These teachings evolved into Ennis's philosophy of "soft power," in which what matters most is listening to one's inner voice and living on one's own terms. The approach may have kept Ennis's career from reaching superstar levels, but it also kept her content with herself and her life.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"There are so many great artists that weren't always in the limelight; they made a conscious choice to be in their community and to uplift and do great art there," Ali said. "Ethel did both, but she wasn't mesmerized by that. I'm always intrigued with that because as a young woman artist, those crossroads of trying to figure out what is stardom and how to show up and represent yourself in the world can have you really detached from your true soul. If I feel that way, I know somebody else can feel that way."

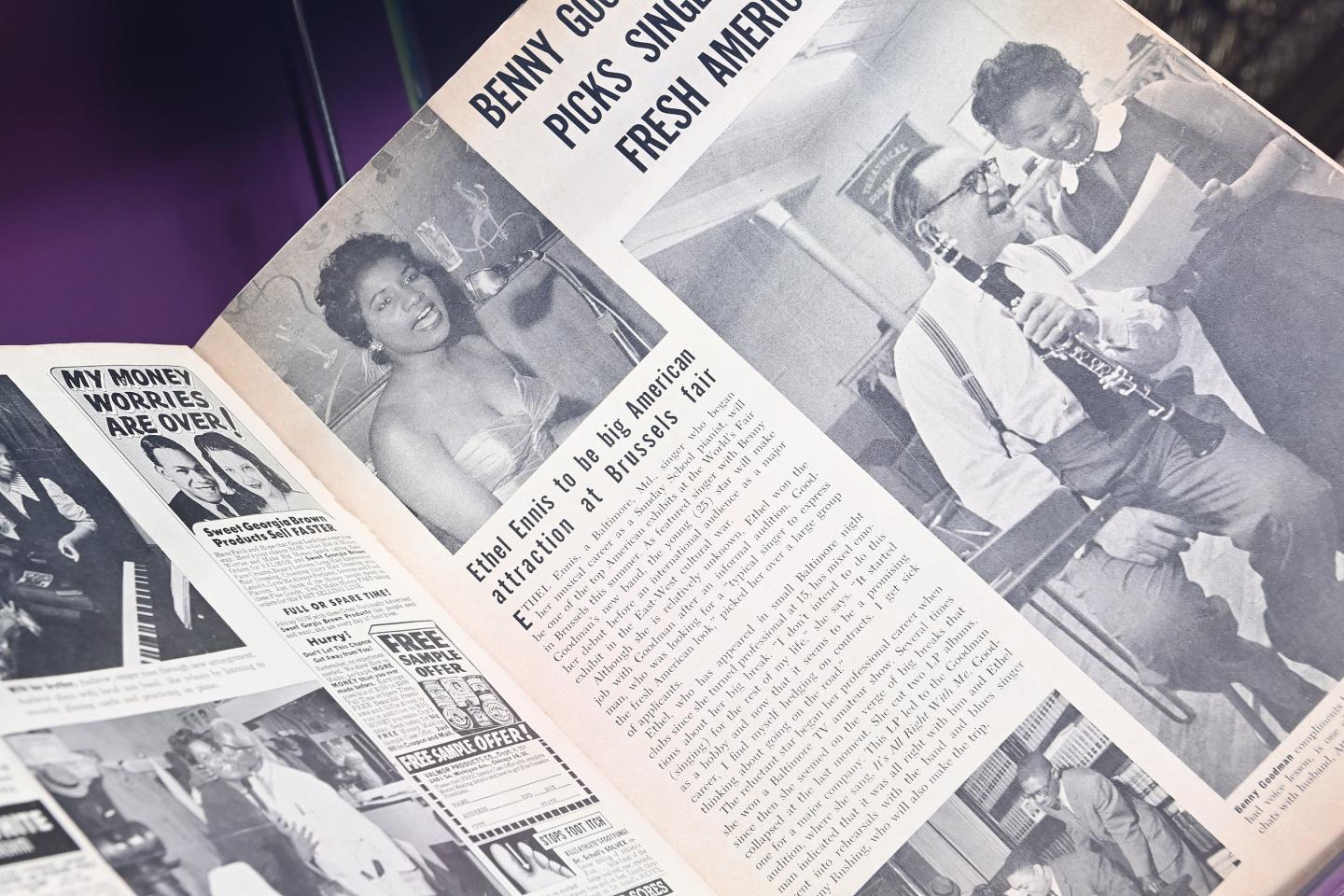

Over the years, Baltimore's "First Lady of Jazz" shared stages with the likes of Miles Davis, Benny Goodman, Cab Calloway, and Dizzy Gillespie. She sang the national anthem at Richard Nixon's second inauguration and performed at the Jimmy Carter White House. In 1984, she and Arnett opened Ethel's Place, a club across the street from Baltimore's Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, which showcased acts ranging from the local to marquee names until they sold it in 1988.

In the exhibit gallery, the large neon blue "Ethel's" from the club hangs prominently on the wall. On display are album covers, unpublished musical arrangements, correspondence, news clippings, and photographs. Concert posters adorn the walls, along with quotes by Ennis—for example, "If I can wake up the people's spirits, I'll know my time on earth will have been worthwhile."

A map tracks her Baltimore presence, beginning with the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood where she was raised, her church, and her music teacher, and moving on to her concert venues and sites of civic engagement and activism. Ennis's seven-decade performance career may have taken her to stages and television screens around the world, but she always returned home.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Posted in Arts+Culture, Community

Tagged exhibits, sheridan libraries, jazz, george peabody library, africana studies