For students in the Environmental Justice Workshop at Johns Hopkins University, going to class means boarding a van and driving to South Baltimore's Curtis Bay neighborhood. In a modest rec center there, they gather with members of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust and other activist neighbors. Together they try to understand how the various industries in the area were allowed to cause such widespread damage to the community and to develop a vision for a healthier and more just future.

Image caption: This history of environmental hazards in the area was researched, written, and spoken by members of the class, the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, the Community of Curtis Bay Association, and the Ecological Design Collective, and packaged by filmmaker and producer Krishnan Vasudevan, assistant professor in visual communication at the University of Maryland.

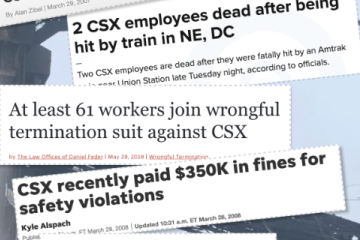

Just down the street is the CSX Coal Terminal, where in December 2021 a coal silo exploded after methane built up inside. Homes were damaged, windows shattered, and the coal dust from the explosion settled on top of the coal dust that has coated the community for years, drifting into people's homes, cars, and lungs.

Residents have been lobbying for many years to stop CSX, the rail-based freight transport company, from exporting coal out of Baltimore. A landfill, wastewater treatment plant, and medical waste incinerator sit nearby. Activists call the area a "sacrifice zone," where industry is allowed to endanger residents who often can't afford to leave. The Hopkins graduate and undergraduate students in the course join the activists in their quest to research the issues and develop alternatives that prioritize both residents and industry workers.

"There is so much work we have to do to deepen our relationships as a university with the rest of the city that we happen to be located in," says Anand Pandian, professor in the Department of Anthropology at the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and co-instructor of the year-long course. "We've been working all year with communities ringed by industry, and so much of the infrastructure that keeps the city going is located in zones like this. So even if we don't consciously acknowledge the connection to ourselves, it remains in the material underpinnings of our existence here. If we are implicated, then what responsibility do we have?"

The Environmental Justice Workshop is a community-engaged course, meaning that it operates on principles Pandian learned as an Engaged Faculty Fellow at Hopkins' Center for Social Concern from 2019 to 2020. Such courses partner with community members and institutions in a two-way process, with the community teaching the students and the students contributing to the community.

Shashawnda Campbell is co-teaching the course as a lecturer in the Krieger School. Campbell graduated from nearby Benjamin Franklin High School, and later helped develop the South Baltimore Community Land Trust as a means toward community-led development, permanently affordable housing, and zero-waste infrastructure. The course is a project of the Ecological Design Collective, a community for ecological imagination and collaboration that Pandian and Campbell co-curate along with other researchers, designers, activists, and others in Baltimore and beyond. Last week class members held a listening session with the secretary of the Maryland Department of the Environment and other agency representatives, and participated in a collaborative brainstorming session.

The course has run for a full academic year, giving students the option to sign up for one semester or two. There are readings and discussions, but the experience is less about papers and exams, and more about an array of projects and resources designed to give students practical experience with research and analysis in support of the residents' ongoing efforts. Examples include a web page that offers a critical analysis of CSX's past and present activities; a video in which class members share research findings; a report offering alternatives to shipping coal through the area; a proposal to preserve a former landfill as an environmental amenity; and a vision for a community environmental justice center that will occupy a building near the rec center.

"We began our introductory discussion by trying to determine how the 64-acre green space could be utilized," wrote Ari Harris-Kupfer, a junior majoring in civil and systems engineering, on the class blog. "We had questions like, 'What is considered a win for the space? Is it developing the space into a zero waste park, or leaving it be but protecting it from industrial development?' Next week we will meet with Baltimore Green Space to learn more about the work they do in the city to protect green spaces and ask them questions such as, 'How do green spaces improve community health? What has worked to protect other green spaces? And is there typically opposition to protecting green spaces.'"

Image caption: Anand Pandian, left, joins students for a protest for environmental reparations in Curtis Bay

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The course's location invites students to take on the role of field workers, and to broaden their understanding of what education is, Pandian says. Students read about the area's history and listen to lifelong residents describe their experiences. They research air quality reports and also breathe in the overlapping smells of multiple industries. They review patterns of disinvestment and huddle into their coats when the thermostat stops working in the under-resourced rec center.

"There's something about the way in which a classroom education is structured that often makes it difficult to acknowledge that our learning in the world is a multisensory learning, that the sensations that we have are essential to the insights that we can gather," Pandian says. "We have a great deal to learn from proximity and exposure to the things that we're trying to understand."

Also see

And as the students connect field research with environmental justice, they become poised to explore new avenues of discovery, he says. Environmental anthropology has a lot to offer humans at this moment of pivotal climate change. If, as many scholars believe, we are in the Anthropocene—an era geologically defined by the prominence of human beings—then a field devoted to the study of humans should have something important to say, Pandian says.

"Anthropologists are prepared to wrestle with those problems because we try to make sense of human motivations, because we try to understand how human cultures and societies are organized, because we have ways of explaining why the problems that we face are so intractable, but also why things sometimes crack open in interesting ways," Pandian says. "That's what this class is about: finding those openings into a more livable and sustainable future for the residents of Baltimore and the environment that all of us share."

Posted in Student Life, Community

Tagged anthropology, community, sustainability