An advisory panel for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended emergency use authorization, or EUA, for the two-dose Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for people 18 and over. But unlike other COVID-19 vaccines that have gone through the process, there's been a delay between the recommendation and actual authorization for the vaccine while the FDA investigates its manufacturing processes.

For insights into the vaccine, its development and manufacturing, and what impact it might have on vaccination in the U.S., the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health reached out to William Moss, executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center. He sheds light on what's causing the EUA delay and what we might expect to see next in the process.

Tell us about Novavax. What makes this vaccine unique from other COVID-19 vaccines in the U.S.?

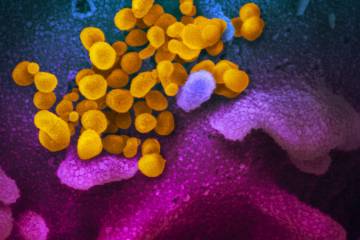

This is a different type of vaccine than what we currently have under EUA here in the United States. We have two messenger RNA, or mRNA, vaccines and the Johnson & Johnson adenovirus vector vaccine. All those vaccines introduce the genetic recipe for the spike protein into our cells, and then our own cells make the protein to which our immune system responds.

The Novavax vaccine [was built with] a much older technology for vaccine development where, instead of injecting the genetic recipe, we actually inject the protein. It [uses] a combination of spike proteins that form what are called nanoparticles, which group together. The Novavax vaccine also has an adjuvant, an immune stimulant to get a better immune response. In some ways, this is an older technology. The protein is made outside of the human body and then injected into us, and that induces the immune response.

What other vaccines have been built this way?

There are a number of widely used vaccines that inject the protein of the virus or the pathogen, like the Human papillomavirus (HPV) or the hepatitis B virus. People will also be familiar with tetanus toxoid vaccines or diphtheria toxoid vaccines as part of a childhood vaccine series.

What do we know about the side effects of the Novavax vaccine?

Protein-based vaccines tend not to have serious side effects. There can be soreness and redness at the site of injection.

In the Novavax clinical trial of about 40,000 people, there were six cases of myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle, and one in the placebo group. That suggests a differential in risk. It seems to be more common in younger men—although the numbers are very small. It's somewhat similar to myocarditis or pericarditis, inflammation of the tissue around the heart, that has been observed with the mRNA vaccines.

That side effect was not seen in clinical trials of the mRNA vaccines. It was only [seen] when the vaccine was rolled out into the general population and millions of doses were administered. [Because] this was seen as a potential adverse event in the clinical trials, which is a much smaller group of vaccine recipients, some FDA advisors thought that there should be a warning should Novavax receive an EUA.

There is no doubt that the risk [of getting myocarditis from a vaccine] is much smaller than the risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 infection.

How is this standing up to omicron subvariants?

This is still a big unknown, and we certainly don't have any data from the U.S. on this.

The clinical trial data on the vaccine's efficacy looked good—90% overall. It was lower in older adults over 65—about 80%. It's expected to get lower efficacy in that higher risk group.

That was during a time when the alpha and beta variants were circulating in the U.S., before delta and omicron. We have certainly learned with mRNA vaccines that efficacy, particularly against mild disease or asymptomatic infection, is much lower with omicron and sub-lineages of omicron. We also know that a third dose—a first booster after the primary series—is critical to achieving higher levels of protection from the mRNA vaccines against omicron and the subvariants.

This is a big unknown about the Novavax vaccine: How will it stand up, particularly when used in the primary series against the omicron variant? I have no doubt the efficacy is going to be much lower than 90% based on our experience with the mRNA vaccines.

There is still a question as to whether the Novavax vaccine would have benefit as a booster dose for people who received a primary series with an mRNA vaccine, or even a primary series plus a booster, but the current emergency use authorization under FDA consideration is just for the primary series, not for a booster dose. Novavax is conducting studies of the vaccine as a booster dose.

Novavax was part of Operation Warp Speed, but what took it so long to come online?

Novavax—a biotech company in Gaithersburg, Maryland, that had not brought a vaccine product to market before—received $1.8 billion from the U.S. government under Operation Warp Speed. The government was trying to diversify the vaccine platforms and not put all of its eggs in one basket. We had no idea when [Operation Warp Speed] started how well the mRNA vaccines would perform.

Where Novavax ran into obstacles with the scaling up of manufacturing, and that continues to be a challenge for them. They were a relatively small biotech company, and they didn't partner with the big vaccine manufacturers. Bio-N-Tech, for example, which developed what we now refer to as the "Pfizer mRNA vaccines," partnered with Pfizer, [which] allowed them to scale up manufacturing very quickly even though it was a novel vaccine platform. Novavax has now partnered with the Serum Institute of India, the world's largest vaccine manufacturer to produce their vaccine—though not yet for the U.S. market.

When the FDA approves a vaccine, they look not only at the result of the trials—safety and efficacy—they carefully consider the manufacturing process and that's where things are getting delayed. Novavax has conducted clinical trials outside of the U.S., but because the manufacturing process was different, the results of those studies were not considered by the FDA.

Typically, what we've seen in the U.S. is, very shortly after the FDA advisory group issues a recommendation like they did for EUA, it's fully endorsed by the FDA. Then it goes to the Advisory Committee of Immunization Practices at the CDC, and the CDC director signs off on it. We're seeing a very different process here: There's a delay between the recommendations from the FDA advisory group to the FDA actually making an EUA, and that's largely because of their continued investigations into the manufacturing process.

[The FDA] needs to be absolutely confident that the product being produced and delivered in the U.S. meets all the regulatory requirements and is the product that was tested, for which we have safety and efficacy data.

Do you think the delays could affect whether vaccine-hesitant people will get the Novavax vaccine?

This is still a black box. About 80% of the U.S. population has received one dose [of a COVID-19 vaccine]. About two-thirds are fully vaccinated, and of those eligible, only 50% have gotten a booster dose. Vaccination trends in the U.S. are pretty flatlined. I am unsure how much of a difference this [vaccine] is going to make.

This is being pitched as a more traditional protein-based vaccine platform. There might be people out there who have decided not to get an mRNA vaccine because it is a new platform—although, we have more information on the mRNA vaccines because of how many people have been vaccinated here in the U.S. than probably any other vaccine.

My forecast is that this is going to have a marginal effect. I don't see a big rush to get vaccinated among those who have already decided not to. I hope I'm wrong. I hope that there is a sizable population who have been waiting and this is their opportunity, but I'm not that confident that this is going to happen.

Why do we need another vaccine in the mix?

I think it's useful to step back and ask: What would the ideal COVID vaccine look like?

We would like one that has long-lasting immunity, eliminating the need for frequent boosters. One that is protective across variants—a universal coronavirus vaccine. One that had fewer side effects. One that would be easier to store and administer, and this is where I see a niche for Novavax. Not necessarily in the U.S., but in low- and middle-income countries that just don't have the capacity for the cold storage that the mRNA vaccines require. These protein-based vaccines have less stringent cold chain requirements, so there may be more global demand.

There's still a huge need, great inequities, and many vulnerable populations in many countries who need to be vaccinated. Perhaps, that's where the real value of Novavax and other protein-based vaccines are: their familiarity as a vaccine platform and fewer logistical storage issues.

When might we actually see emergency use authorization by the FDA?

It will depend on what the FDA finds out about the manufacturing processes. It's possible that, if all goes well, it could be this month, June. That's what the company is hoping for. If not, unless there are major manufacturing issues, I would hope for some time in July.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged william moss, covid-19 vaccine, international vaccine access center