In 2016, the writer/historian Lawrence Jackson ended a 14-year career teaching at Atlanta's Emory University, moved to Baltimore, and bought a house.

A very nice house: a meticulous, stone colonial some 2 miles north of Johns Hopkins' Homewood campus in one of the city's loveliest neighborhoods, Homeland. There's a detached garage out back, a slate roof overhead, and a Doric-columned portico over the front door. Stepping up the academic ladder and stepping into a handsome home engenders a prideful sense of achievement. But for Jackson, hired as a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History, the move also fostered internal disquiet.

This was not just a relocation for the Black, divorced father of two, but a return to a city where he grew up and still has family. But the Baltimore of his youth was both poverty-scarred and overwhelmingly Black—far removed from his now leafy pocket of white affluence. Ruminations on his homecoming to racially bifurcated Baltimore form the backbone of his new book Shelter: A Black Tale of Homeland, where memoir meets history lesson meets the contemporary pursuit of social justice.

"It's a complicitous critique of the position of the Black middle class," Jackson says of a work fueled by the Guggenheim Fellowship he was awarded in 2019. "The idea of shelter—this fundamental thing—is here evoked as a moment of betrayal or treason to my race or certainly a treason to a cause: the overthrow of historic segregation."

Or, as he frames it in the book, some of his round-the-way friends consider him an Uncle Tom while his new address raises eyebrows of some progressive white colleagues who envisioned him settling in a "diverse" neighborhood. Jackson justifies his Homeland mortgage in practical and patrimonial terms: a chance to pass some generational wealth to his children. (Something, he writes, that had yet to occur in a family whose Baltimore roots go back nearly a century). Indeed, about the same time he buys in Homeland, the family sells his late grandmother's house in that other Baltimore for $5,000—less than the purchase price in 1965. Meanwhile, real estate websites say the median listing home price in Homeland is approaching $700,000, up more than 20% from last year.

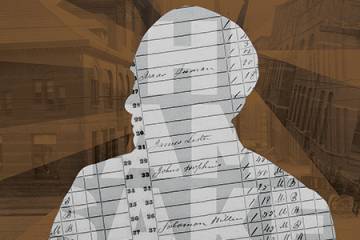

Homeland, its now resident historian discovers, arose on the grounds of a namesake estate almost certainly built with enslaved labor by David Perine, a longtime friend of Roger B. Taney who led the Supreme Court during its Dred Scott decision denying Black people civil rights. During Homeland's first decades, Jackson would have been barred from buying there. Developer literature from the 1930s tucked language that prohibited Black people from dwelling in Homeland under the general heading of "Nuisances." (Working there was another matter, and Jackson discovers vestiges of a Homeland "maid walk," a narrow footpath between and behind houses allowing domestic workers to negotiate the neighborhood without being seen on the main roads.)

There is unease on the academic homefront as well. Jackson writes that it never seemed likely that he would land at Hopkins, a school he had considered elitist and exclusive. While he allows that Hopkins might do a better job than other urban universities in addressing racially charged town and gown issues, when he gets wind of plans to create a campus police force, he joins a group of Black faculty approaching the university president's door to object. "To be African American, from Baltimore, working at Johns Hopkins, you have to understand that some people will always be looking at you sideways," Jackson says.

The history lessons include his own sometimes troubled youth and experiences with guns, street brawls, and police abuse. His father's untimely death when Jackson was 21 served as wake-up call. "I had to grow up and be responsible for myself and start to think more seriously," he says. His academic knuckling-down culminated with a PhD from Stanford University and spared him the fate of his friend Donald and the many other neighborhood and schoolyard peers whose lives ended on the unforgiving Baltimore streets.

Jackson's return to Baltimore also brings him back into the fold of his family church, St. James Episcopal on the border of Sandtown, a distressed neighborhood made infamous after Freddie Gray's death in a police van touched off weeks of civil unrest. Here, though, Jackson finds beauty: a joyful jazz concert in Lafayette Square, an underutilized patch green across from his church. In an atmosphere of peace and harmony, local musicians and Peabody Institute instructors perform.

Also see

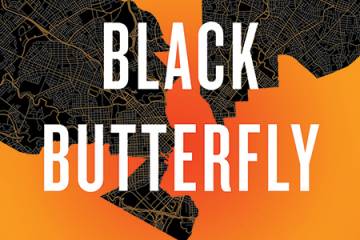

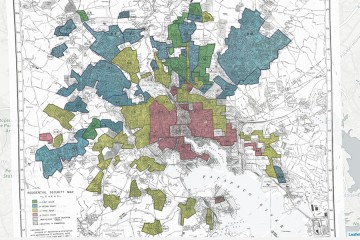

In the book's final third, Jackson gains his sea legs navigating life with a foot each in the "White L" and the "Black Butterfly"—geometric descriptors for the city's de facto apartheid based on how populations appear on the map: White Baltimore runs down the city center to hang left at the waterside while Black Baltimore splays out east and west from midtown like wings. He increasingly sees his role at Hopkins as conduit between the two worlds, writing: "Life improved for everyone with the obvious realization of value and mutuality between Sandtown's Harlem Avenue and Homewood." One of his first projects was archiving and publishing the photos of unheralded Black street photographer John Mayden. (Jackson has since founded the Billie Holiday Center for the Liberation Arts, whose mission is to foster "organic links between the intellectual life of Johns Hopkins University and the city's historic African American communities.")

The book's final chapter contains lush and lyrical descriptions of yardwork as Jackson assiduously tends to his fescue and mulches his plantain lilies. You sense him taking ownership of his property, of his decision, of his Homeland. "I had long wanted to write something reflective of my return to Baltimore," Jackson says. "Art is the catharsis. But what I really wanted to do was write a beautiful book. I hope I wrote a beautiful book."