Carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels comprises about 80% of the human-made greenhouse gas emissions contributing to the Earth's rising temperature. Two researchers affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Ralph O'Connor Sustainable Energy Institute are working on a way to pull those harmful gasses out of the air and convert them into a form of solid carbon useful in applications ranging from farming to construction.

"If we can do this, we would be the first in the world to demonstrate a complete carbon-to-carbon route, in which so-called 'bad carbon' is transformed into a globally useful 'good carbon,'" said Jonah Erlebacher, a materials science and engineering professor who is teaming up on the project with Chao Wang, an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering—both at the Whiting School of Engineering.

The research is one of the new institute's five first initiatives. Others include the production of new batteries with integrated solar energy capture, creating a publicly accessible database from world-class wind farm simulations for researchers to use, and developing a high school outreach program around sustainable energy.

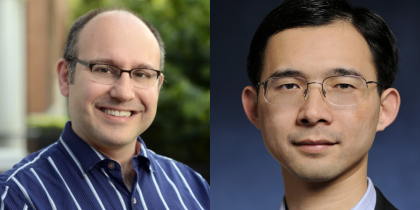

Image caption: Jonah Erlebacher (left) and Chao Wang

"These types of investments on critical challenges that can impact our sustainable energy future is what ROSEI is all about," said ROSEI Director Ben Schafer, a professor of civil and systems engineering at the Whiting School.

This is not the first time scientists have tried to combat CO2 emissions by turning it into a different substance, but most previous attempts processed it into fuels such as methanol, which create their own CO2 emissions when re-used.

Erlebacher and Wang see pure carbon as a building material whose potential impact could rival that of steel in the 19th century during the industrial revolution.

"Pure carbon is strong but lightweight, fire-resistant, and can also be made into any shape, giving it the ability to be used in so many ways," said Wang.

They say that pure carbon could be used in automobile manufacturing, textiles, and in biochar, which helps fields retain moisture, fosters the microbiome under the ground, and improves crop yields.

Initial research will take place at a facility in Columbia, MD, now being renovated. However, Erlebacher and Wang also plan to involve the power plant behind Maryland Hall on the university's Homewood campus in their research.

"The big vision for us is to take the exhaust from that power plant, which is significant, run it into our labs at the back of Maryland Hall, and convert it to solid carbon. Essentially, just sequestering all that carbon dioxide and turning it into solid carbon," Erlebacher said. "We'd literally reduce the university's carbon footprint, and it would make for a great demonstration project."

Integrating the power plant's exhaust is not the only way Erlebacher and Wang see the initiative evolving. Wang, for instance, thinks that this research could lead to carbon emerging as a major entity in the stock market, which would allow students who study finances to get involved with the initiative.

"There will be a policy side of this project, an economy side of it, and a power system side of it. Looking at how this carbon neutral or decarbonized economy is going to work will be important," Wang said. "I think there could be something of a carbon revolution somewhat soon because many countries have said they are going to try to be carbon neutral in the near future. There are so many industries that need to be redesigned so we can lessen the carbon emissions to hit those goals, so coming up with new practices that will help with that could become an exciting career. This is an opportunity to make a big impact."

Erlebacher and Wang, who are longtime collaborators, have talked about pursuing this research many times over the years, but found that the establishment of ROSEI last April provided the platform they needed to get going.

"The existence of ROSEI helps create a framework for us to collaborate on this initiative," Erlebacher said. "We are no longer working in a vacuum; we are working towards a shared goal with an institute full of researchers who have the same values and aspirations as we do."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged sustainability, carbon, ralph s. o'connor sustainable energy institute