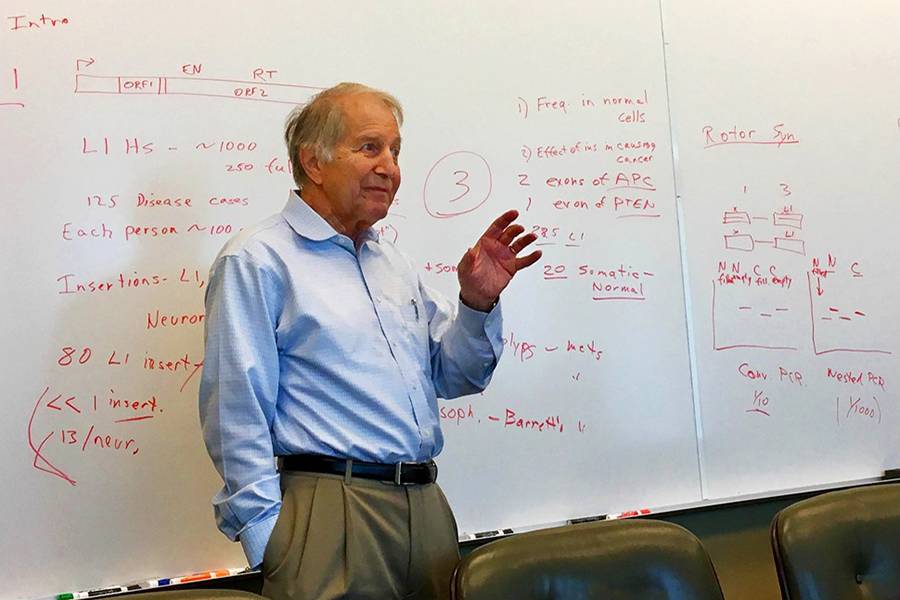

Haig Kazazian Jr., a pioneering scientist in the field of genetic medicine, died Jan. 19 of congestive heart failure. He was 84.

Born to Armenian parents who survived genocide during World War I, Kazazian, a resident of Baltimore, directed several genetics services at Johns Hopkins and made pivotal discoveries in human genetics, including identifying the molecular basis of hemoglobin disorders, hemophilia, and the role of mobile DNA elements known as transposons, or "jumping genes," in human disease.

"Dr. Kazazian contributed many seminal discoveries to the field of genetic medicine and science, and particularly introduced the practice of prenatal diagnosis of hemoglobin disorders to the world," says Ambroise Wonkam, director of the Department of Genetic Medicine and the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "He will be also remembered as a great activist and advocate for making genetic medicine more accessible to all patients."

Kazazian received his undergraduate degree from Dartmouth College and started medical school there. He completed the last two years of medical school at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, graduating in 1962. He completed his residency in pediatrics at the University of Minnesota and Johns Hopkins Hospital. He completed training in human genetics at Johns Hopkins and the National Institutes of Health.

In 1969, Kazazian joined the Johns Hopkins faculty. During his career, he established the first DNA diagnostic laboratory and directed the pediatrics genetics unit and the Center for Medical Genetics at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Kazazian left Johns Hopkins in 1994 to chair the genetics department at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He was chair of the department until 2006 and retired in 2010. Then, Kazazian returned to Johns Hopkins to continue research in the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine. He remained on the faculty at Johns Hopkins as professor of genetic medicine, pediatrics, and molecular biology and genetics until his death.

"Haig was a great colleague, terrific scientist, a genetics enthusiast, and, most importantly, an amazing source of encouragement and advice for all of us, particularly those early in their careers. He loved his work, and was a wonderful role model. Genetics at Johns Hopkins won't be the same without him," says David Valle, professor of genetic medicine and former director of the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine and the Department of Genetic Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

In one of his earliest discoveries, Kazazian worked with Stuart Orkin to characterize mutations that cause beta-thalassemia, a common disorder of inadequate production of hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in red blood cells.

Later, when Kazazian was studying mutations in hemophilia, he and his lab members found the first example of disease-causing mutations resulting from "jumping genes," or transposons. These mobile segments of DNA can sometimes cause disease by inserting into and disrupting a functional gene.

In 1999, Kazazian and fellow scientist Arupa Ganguly were among the first plaintiffs in the 2013 Supreme Court ruling that companies cannot patent parts of naturally occurring human genes.

Scores of scientists trained in Kazazian's laboratory, including more than 25 postdoctoral fellows. He has published more than 400 peer-reviewed journal articles and a book, Mobile DNA: Finding Treasure in Junk.

Among numerous awards, Kazazian received the Allan Award from the American Society of Human Genetics and the Murray Thelin Award for Research in Hemophilia. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Kazazian is survived by his wife, Lillian; son, Haig III and daughter-in-law, Betsy; daughter, Sonya and son-in-law, David; and five grandchildren.

Posted in University News

Tagged in memoriam, obituaries, haig kazazian