The Homewood campus of Johns Hopkins University has a long history as a site where enslaved people lived and labored. Today, a coalition of university departments and programs will honor the lives of those men and women who toiled on the property and reflect upon the legacy of slavery in America more broadly.

The Ritual of Remembrance is a first-of-its-kind musical celebration at the university that will feature the Baltimore-based African musical theater ensemble Urban Foli and the performance of an original monologue written for the event. The ceremony will begin at 1 p.m. at Homewood Museum, an early nineteenth-century estate overlooking what is now known as the Beach on the university's Homewood campus, before moving to the Glass Pavilion for indoor programming, followed by a recessional back to the museum. A Wall of Remembrance—a large banner for the purposes of this event—will bear the names of the enslaved Black people who lived and worked on the Homewood property, and a recitation of their names will be accompanied by a traditional libation, or pouring out of water, in accordance with West African traditions for honoring the deceased.

"The ritual of libation holds the belief that saying people's names keeps them alive. It makes them free. It carries their personhood beyond their physical time on this earth," says event organizer Jasmine Blanks Jones, a postdoctoral fellow in the Program in Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship who is also part of Inheritance Baltimore, an interdisciplinary program for humanities education, research, and community engagement in Baltimore. "By speaking the names of those enslaved at Homewood, we carry their personhood through centuries."

The event also serves as the conclusion of the Center for Social Concern's Intersession courses under this year's theme of "more than a single story." The CSC is a co-organizer of this event.

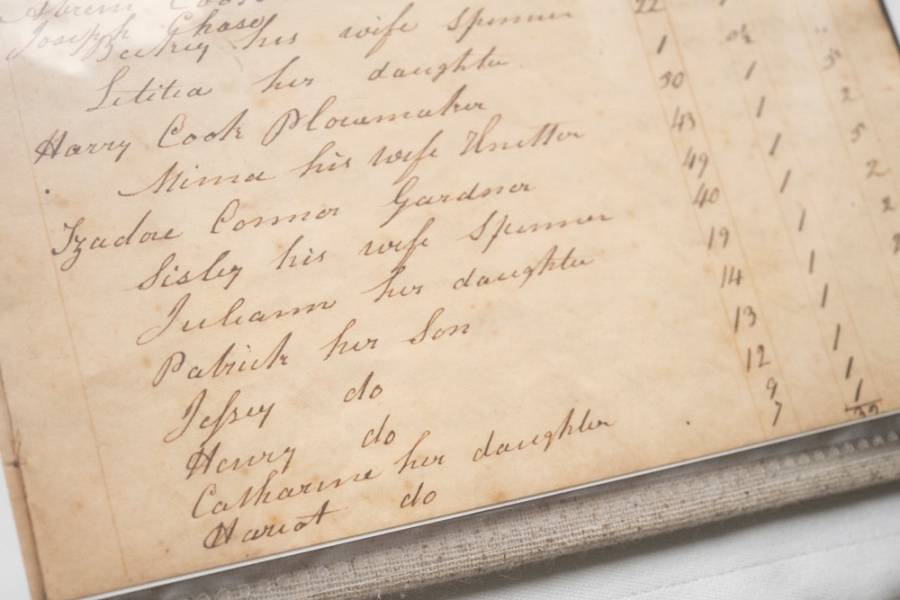

It is difficult to assess the number of enslaved people who lived and worked at the property where the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus now sits, and the Ritual of Remembrance relies heavily on scholarship undertaken in recent years by Homewood Museum with support from Johns Hopkins University. A multiyear research project, "Enslaved at Homewood," recently delved into the historical record, including census records, business ledgers, and personal correspondences to uncover as much information as possible about the enslaved families and individuals who lived at Homewood.

The property was purchased with the intent to become a country estate in 1800 and was a gift to Charles Carroll Jr. upon his marriage. But, as described in a 2018 report authored by Hopkins alum Abby Schreiber, the wider Carroll family held extensive properties and often shared resources amongst themselves, including the labor of enslaved people. As many as 36 enslaved individuals may have lived at the property over time, including Izadod and Cis Conner and their 13 children; William and Becky Ross and their children Richard and Mary; and Charity Castle.

For decades, Homewood Museum tours focused on the architecture of the building and the affluence of the Carrolls. The "Enslaved at Homewood" research project helped bring greater visibility to the lives of those enslaved at the property. The lives of the Carrolls, Conners, Rosses, and Charity Castle are now the subject of guided tours of Homewood Museum.

"This research is absolutely vital to our mission at Homewood Museum to tell the full story of the house and helps us to highlight those forced into an inhumane practice as people who also loved, lost, and endured," says Michelle Fitzgerald, curator of collections for JHU Museums, a co-organizer of the event. "There is always more work to be done and discovered about the enslaved individuals who lived here and we endeavor to continue to do that and highlight it through our tours."

Slavery at Homewood persisted after Carroll's death in 1825, when his son inherited the property and sought to make it a productive farm again. The property was later rented out, and slavery likely continued under the estate's new tenants. In 1838, Homewood was sold at auction to Samuel G. Wyman, a Massachusetts merchant who held enslaved people and was sympathetic to the Confederacy during the Civil War.

"The Ritual of Remembrance is a starting point—we don't yet know all the names of the people who were enslaved there, and more names should be added as we learn more," Blanks Jones says. "This event is about more than just remembering them. Let it spark conversations and action."

In honor of the event, Blanks Jones wrote an original monologue from the composite points of view of enslaved women who were held in bondage by the Carrolls. It will be performed by Yasmine Bolden, a first-year undergraduate student in the Center for Africana Studies

"For me, performing this monologue means rebelling against what Black folks are often told about our enslaved ancestors (we are told to forget, to soften the edges of the violence, to completely disremember instead of remember the complex emotions and experiences of our ancestors) and embrace not only our deeply held traditions, but also to make space for the pain and joys that are situated in our bones, passed down from generation to generation, in order to honor the humanity of the people who were so often told or shown through the actions of enslavers that they had none," Bolden says.

The Ritual of Remembrance will include a participatory art project spearheaded by Jeneanne Collins, a community arts fellow in the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts in the Center for Africana Studies, both of which are co-organizing programs for the event. The project will provide rocks inscribed with the names of enslaved people who lived at Homewood, and participants will be invited to place the stones at areas around the Homewood campus or take photos and share them to social media to recognize the enduring presence of these figures. The ceremony will also be recorded for a film project led by Kali-Ahset Amen, assistant research professor of sociology and the associate director of the Billie Holiday Project, to be distributed to Baltimore community organizations.

"In African and African-American traditions, personhood includes community, it includes our land and our ancestors and those not yet born. That's what it means to be human," says Blanks Jones. "A thorough reckoning with what it means to be human in the current moment requires us to acknowledge our history."

Other co-organizers of the event are the Program in Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship; the Hopkins Retrospective; and the Winston Tabb Center for Special Collections Research.