Every day gets hotter than the one before

Running out of water, it's about to go down

Go down/Air that kill the bees that we depend upon

Birds were made for singing, wakin' up to no sound/No sound

—Childish Gambino, "Feels Like Summer"

We experience climate change not only through higher temperatures and more powerful storms, but also through films, music, literature, and photographs, according to anthropologist Naveeda Khan. The stories and images become part of how we perceive the phenomenon, she says. They also shift our view of climate change from being just a technical problem to solve, lending it power to create new social and cultural spaces in our lives.

In Khan's "Picturizing Climate Change" course last semester, students used portrayals of climate change in a variety of media—including the Childish Gambino hit song "Feels like Summer"—to plumb the ethical, political, and aesthetic issues at stake within them, and to explore the concerns and desires climate change gives expression to.

In a semester when the world still felt hemmed in by the virtual nature of most interactions, Krieger School faculty and teaching assistants had to draw on their creativity to connect with students through screens. Sometimes, though, the limitations turned inside out and offered unpredicted windfalls.

Khan, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology, says her class took a surprising turn. Quite unexpectedly, she says, Zoom turned out to be an ideal format for the topic, giving rise to levels of student engagement and quality of projects surpassing anything she'd seen in 18 years of teaching.

"I realized that actually the Zoom platform allowed me a lot of flexibility to do things that I couldn't even have done if it had been in an in-person class," Khan says. "I really came into my own as a teacher."

The biggest difference was that the 20 students quickly took on the responsibility of teaching one another, Khan says. She shifted assignments that are typically heavy on long books toward shorter articles instead, and made use of the virtual platform to have students post responses to weekly prompts about the readings, respond to one another's posts in writing, and then bring the conversations started in writing into the virtual classroom.

The students' ownership of the class showed up most powerfully in their final presentations, which used media to explore the ways climate change is portrayed, and the degree to which climate change and the ways we think about it are interwoven into our culture.

Senior molecular and cell biology major Jessie Kanacharoen created a time-lapse film showing an image of the Homewood campus "beach" being photoshopped into an actual beach flanking an ocean summoned to North Charles Street by climate change, juxtaposed with the same beach image now choked in photoshopped smog. Senior international studies major Xabier Mcauley made a short documentary about two artists discussing the role of climate change in their work. Senior Carlea Williams-Locks, also majoring in molecular and cell biology, offered examples of types of dance that speak about climate change through the body.

Miki Chase, Khan's TA for the course and a PhD candidate in the department, attributes the power of the presentations largely to the greater accessibility and lack of pressure students may have felt knowing they would be presenting on Zoom instead of in a classroom.

"I think that the pressure of presentation might feel different in a physical space," Chase says. "It's almost democratic when you have a presentation that's being given and it's just another box on Zoom, and everyone is a box on Zoom."

This was the first time Khan taught this course, but it won't be the last; she's planning to teach it as a first-year seminar in spring 2022, noting that the experience proved climate change as an effective portal into the work of anthropology. "We went from studying climate change in itself to studying how climate change has become a powerful lens through which to examine our contemporary society and entangled lives, lending new perspectives on topics such as the global north-south divide and racism," she says.

Meanwhile, Khan continues working to make the humanities and social sciences newly relevant to contemporary issues by co-teaching a course this fall on rumors, conspiracy theories, and disinformation with media theorist Bernadette Wegenstein, professor of media studies, and literary theorist Rochelle Tobias, professor of German, both in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures.

All over the map

Khan's was not the only course to find a different kind of success during the altered semester. Casey Lurtz, assistant professor in the Department of History, drew the students in her "History Lab: Making Maps of Mexico" course into her own research using a format the department has developed to boost undergraduate involvement in research.

For the 1900 World's Fair in Paris, Mexican officials planned to compile a volume of agricultural surveys demonstrating to the world how connected and modern the Latin American nation was in order to showcase its opportunities and attract foreign investment. The volume was never produced, but the surveys—large spreadsheets documenting agricultural productivity through measures like land size, yield, and irrigation—endure.

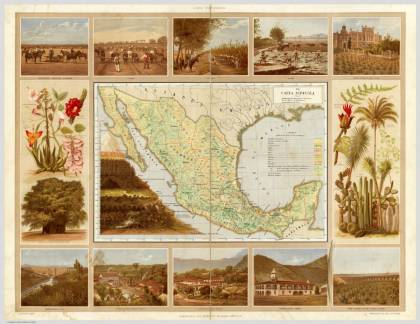

Image caption: Source map used in Casey Lurtz' history lab "Making Maps of Mexico"

Lurtz and her research assistants had already transcribed the surveys, but now she and her students were faced with making them accessible and useful. To create a fuller picture of fin de siècle Mexico, Lurtz wanted to develop StoryMaps, online resources encompassing maps, descriptions, photos, and text.

But to convince the data to offer up these insights, the class needed to learn to manipulate it. Enter Reina Murray, Lena Denis, and other members of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library's Data Services department, who stepped in to guide Lurtz and her students through an array of digital humanities tools to make sense of the surveys and put the information into maps and databases where it could be sorted and analyzed.

And that's when the magic happened, Lurtz says. As some students gained proficiency with some of the tools and others with other tools, they all began to teach one another. Together, they learned to create meaning from numbers and, eventually, maps to illustrate that meaning.

"Watching their endurance and their teamwork, and their creativity with all of this, was really fun and made me very happy to show up on Zoom every week," Lurtz says.

Like in Khan's class, Lurtz's students funneled their enthusiasm into their final projects, which were StoryMaps about something in the research that had sparked their interest. One student followed her curiosity about early 20th century Mexican railroads. Another explored indigenous influences in Mexican mapmaking. A third initially planned to study how climate change was represented in Mexican maps but, when she discovered that no such information was available, instead explored how historians work around the absence of data, creating a StoryMap that thinks through alternate sources of information.

"I think their work and the class as a whole represent the best of what liberal arts education can be: hands-on, interdisciplinary, research- and skills-focused, while also some really big critical thinking questions about the creation and use of data and maps, who makes it into the historical record and the work of scholars, and how we hold space for those archives try to silence," says Lurtz, who created a StoryMap to document the class.

No pressure

Jamie Young teaches a different kind of lab. And this semester, the Department of Chemistry lecturer opened that lab back up for a modified version of hands-on experimentation.

About 530 students had enrolled in Young's Introductory Chemistry Lab course, and most of them opted for fully online classes. But for those who were interested, Young offered two sets of four "practical sessions" each, for students to put into practice what they were learning online and through videos. About 15-20 students attended each session, though Young's socially distanced lab stations could have accommodated 40.

Young couldn't pinpoint an uptick in chemistry knowledge among students who attended the labs. But he did notice a spike in confidence, which he attributes to his decision not to assign points for lab work—the sessions were purely for students to practice, make mistakes, try again, and learn new techniques. The chance to focus on practicing technique with no pressure allowed students to find mastery, he says.

Meanwhile, Young learned something about how students learn, and how he might shift his teaching in future semesters. Typically, labs are designed as step-by-step processes in which students' success is cumulative: an error in Step 2 might result in diminished product in Step 52, typically reducing a student's grade. But watching the freedom in his students last semester, Young realized that students typically begin to tune out after making an early error, while the ability to start over keeps them invested and discovering.

For the future, he's thinking about giving students sample data to use for the graded portion. They will still do their own work in the lab, but they will use it to compare their results with the samples, and discover through self-reflection where they can improve.

"Intro chem is viewed generally like this first hurdle that premeds have to conquer, and I'm the big bad boss that they have to defeat in order to become a doctor," Young says. "And so I'm trying to steer away from that kind of mentality and make introduction to chemistry lab what I think it should be, which is like: 'you're going to practice, you don't know this yet, and it's OK if you get it wrong.' Hopefully one good thing that comes out of this really terrible 18 months is that I can improve the way I teach the labs and improve the way that we market introductory chemistry, and get students to realize this is the premium opportunity to practice lab stuff and build up those lab skills."

Besides the unexpected gifts of this semester's virtual classroom, Young, Lurtz, and Khan each noticed something else: their students' resilience. In a time when Zoom fatigue is real and they know many students and their families are struggling, over and over again, students rose to the occasion and demonstrated the kind of persistence and optimism that transformed classrooms.

"I just want to highlight the students' outstanding commitment and diligence this semester," Young says. "They're Johns Hopkins students, they're intelligent, but this year they really showed an extra level of commitment to themselves, to the future, and to the school too, and I was just massively impressed."

Posted in Student Life

Tagged undergraduate education, coronavirus