A massive, COVID-fueled humanitarian catastrophe is presently unfolding in India, with illness spreading at terrifying and deadly scale and speed. The nation's hospitals and health care system are swamped. Supplies of critical supplies—oxygen, personal protective equipment, medications—have been exhausted or are running dangerously low.

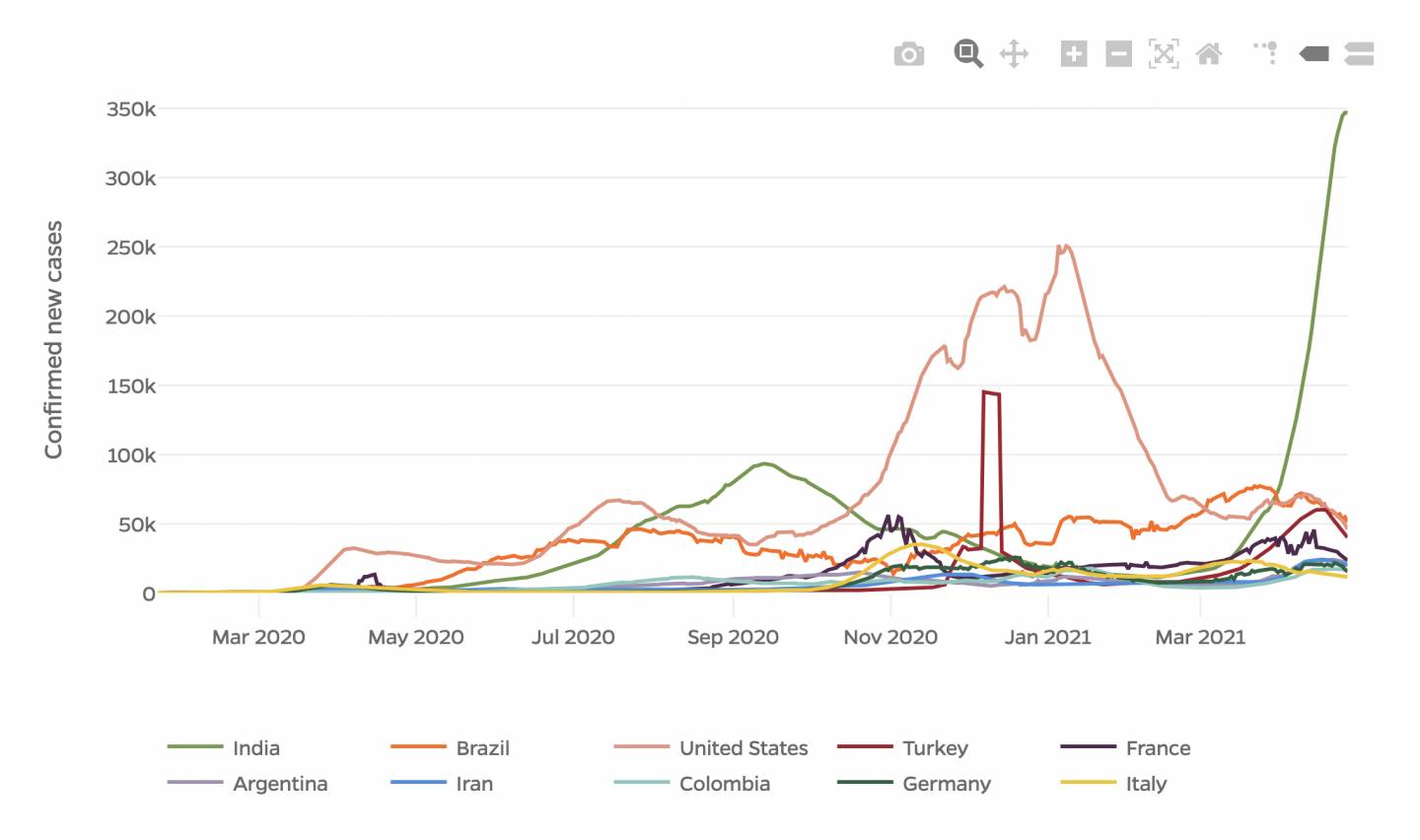

India has recorded seven consecutive days with more than 300,000 new COVID-19 infections, a figure that is larger than in any other country at any point in the pandemic and which, experts say, surely underestimates the true spread of illness. (Daily cases counts in the U.S. peaked around 250,000 in January before falling off precipitously). On Wednesday, India became the fourth country to surpass the grim milestone of 200,000 deaths officially linked to COVID-19, though the actual death toll is likely much higher.

The situation serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of reopening too quickly, even as the pandemic appears to be waning in much of the world. It also serves as an urgent call to action to many in the Johns Hopkins community who are from India or have family there.

"The surge in cases happened quite rapidly," says Amita Gupta, professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health. "The stresses that have been placed on every sector of society are catastrophic."

NEW COVID-19 CASES WORLDWIDE

Image caption: The 7-day moving average of new daily COVID cases in the world's most affected countries shows the exponential growth of illness in India (green line) over the past several weeks.

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center

What happened, it appears, is a convergence of factors, creating a perfect storm that reignited the pandemic.

Experts had long viewed India—home to nearly 1.4 billion people, two-third of whom live in poverty and most living in densely populated megacities—as a potential COVID hotspot. But the nation kept coronavirus transmission at low levels with a lockdown in March, April, and May of 2020. An initial reopening was followed by a first wave—which at its September peak reached about 93,000 new cases per day—but the surge had mostly ebbed earlier this year, with daily case totals falling to around 11,000 in February.

Spring arrived, along with the promise of vaccines, and the country began reopening. People attended weddings and large religious gatherings, spring festivals and cricket matches.

COVID infection began spreading anew, gradually at first, then exponentially. The presence of new, highly transmissible variants may have played a role. A slow vaccine rollout and skepticism about vaccinations surely did. The result has been an enormous second wave arriving seemingly all at once.

"I think that the second wave really snuck up on them," said David Peters, chair of the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. "They were able to keep the initial surge quite low, and things were sort of smoldering along for a while, and then there's been this huge acceleration that they had not expected at this stage."

In response, efforts are under way across Johns Hopkins to marshal resources, energy, and expertise to aid university partners in India in this time of extraordinary need. The newly created Johns Hopkins India Institute—co-chaired by Gupta and Peters—has formed a task force to organize COVID-related activities and communications in India, prioritizing needs identified by partners on the ground. The group is soliciting donations and working to get oxygen supplies, PPE kits, lab supplies, testing kits, and humanitarian resources where they are needed most.

The institute has brought together a constellation of experts from across Hopkins, a multidisciplinary network of scholars and students, each with their own existing connections and partnerships in India. As requests come in from NGOs and others on the front lines there, individuals at Hopkins are making connections to help provide both direct and indirect support.

In the near term, that means addressing acute shortages of medical supplies and therapeutics. Longer term, it means working to ensure that people are getting vaccinated—by advocating for both the release of vaccine stockpiled in countries around the world, providing active pharmaceutical ingredients to vaccine manufacturers in India—as well as dealing with the ripple effects of the COVID crisis, on cardiovascular health, mental health, and many other fronts.

"What happens there affects us all," Gupta says. "There is clearly the humanitarian crisis, but it's also a global problem. As countless infectious disease experts have said, this disease knows no borders. If there are parts of the world where this is going on, we are not safe.

"With such a large COVID case load, there's an increased chance of viral mutations that could be more transmissible and undermine the effectiveness of current vaccine efforts," she added. "And India is also the main producer of vaccines for the rest of the world, so this crisis will have knock-down effects on access to vaccines in other countries. So we really do need to do whatever we possibly can to help."

Johns Hopkins will host two virtual events Thursday to raise awareness of the crisis unfolding in India:

- The COVID-19 Emergency in India: How We Can Help (9-10:30 a.m. EST, 6:30-8 p.m. IST)

- Facebook Live: The COVID-19 Crisis In India (11 a.m. EST, 8:30pm IST)

Among of the participants in the first event will be Brian Wahl, a Bloomberg School epidemiologist who lives and works in Delhi, India's capital city. In partnership with the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, Wahl is part of an ongoing effort to address vaccine hesitancy in India, particularly in rural areas.

"Vaccines are one of the best tools that we have to get out of the current crisis in the medium- to long-term, and unfortunately there is a growing concern around vaccine hesitancy," Wahl said. "Together with partners here, we are working to get messages out and really encourage broader acceptance of vaccines."

Wahl, who has lived in Delhi for 12 years, described the tremendous challenges on the ground, where the surge in COVID cases has overwhelmed health systems and led to "much suffering and many deaths."

"It's created a lot of fear and anxiety," he added. "Even though Delhi is in lockdown at the moment, you still feel the fear and anxiety in the air, whether it's because of the sound of ambulances or frantic calls from friends and family."

To make contributions to the Johns Hopkins India Institute and to learn more about its emergency response to the COVID-19 crisis, visit https://indiainstitute.jhu.edu/covid-19-response-relief/

Posted in Health

Tagged global health, india, covid-19, covid-19 variants, johns hopkins india institute