As the world begins a slow ascent from the depths of a global pandemic, all eyes are now on the field of education as the area of greatest public concern. One year ago, millions of students worldwide ceased learning or had to quickly shift to less-than-ideal and unfamiliar online classrooms in the wake of COVID-19. With a vaccine now in hand and the federal government prepared to pour unheard-of sums into reforming American education, the Hub asked 11 of the leading minds at the Johns Hopkins School of Education what they see as the biggest takeaways from a year like no other and how they would choose to meet the challenges of the coming day.

Christopher Morphew

Dean, School of Education

Christopher Morphew says his first concern was about the massive loss of learning likely to take place as schools shifted to remote education, but that focus later shifted to the mental health of students and teachers and the importance of social-emotional learning. The good news, he says, is that parents have gotten more involved than ever in their children's learning, which has been accompanied by what Morphew calls "wonderful" advances in telecounseling to help them cope. Lingering worries remain not only along familiar social, economic, and racial equity lines but also in teacher pay. "Teachers just aren't paid well enough," he says. If anything, the pandemic has inspired newfound respect for the difficult but critical job educators do. "They deserve to be paid like the professionals they are," Morphew says.

Hunter Gehlbach

Vice dean, School of Education

Hunter Gehlbach's professional attention focused on what he deems to be the three prerequisites for learning: a sense of social connection at school, the motivation to learn, and the self-regulation skills necessary to stay focused on tasks. "All three became much harder in remote schooling," Gehlbach says. The silver lining throughout the pandemic has been the experiential education of parents in their children's education. For the profession as a whole, he adds, the rebounding economy, an influx of federal dollars, and the additional attention placed on education's foundational place in America's success should coalesce into rising professional opportunities for educators.

Annette Campbell Anderson

Faculty lead, School Administration and Supervision

As a former school principal, Annette Campbell Anderson understands the pragmatic challenges of reopening schools. When school closures first came, her worry turned to the most vulnerable students. Millions disengaged, she says, and they must not be forgotten as we return to classrooms. Regardless, remote learning is here to stay, Anderson says, pointing to a recent study showing 30% of parents actually prefer schooling remain remote. The biggest challenge ahead, she says, will be replacing the estimated 1 million teachers who have exited the profession in the last year. That looming gap, however, should lead to opportunity for the graduates of the School of Education.

Bob Balfanz

Director, Everyone Graduates Center

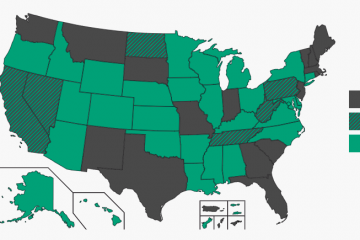

Before COVID-19, Bob Balfanz focused on chronic absenteeism and early warning systems for at-risk kids in an effort to get more kids to graduate. When the pandemic struck, he feared fewer graduates overall and fewer opportunities for those who managed to graduate. Schools solved the first challenge by giving seniors a "free pass" in the final few months of the last school year. That meant more graduates but also a loss of counseling services designed to shepherd them into colleges the following fall. In high-poverty schools, Balfanz says, there was a 30% decline in graduates going directly to college. "Once you lose momentum, it's hard to regain," Balfanz warns. In response, he has stepped up efforts through a network of 75 high schools in six states and the "Pathways to Adult Success" program that helps graduates transition to college.

Laurie deBettencourt

Program lead, Special Education Programs

As school closures set in, special educators got caught between the acute challenges of educating students with disabilities in the online environment and the legal mandates that they must follow. Laurie deBettencourt was concerned the outcome would be traumatic for students, parents, and teachers. Facing a national shortage of qualified special educators and anticipating a further exodus related to COVID-19, school districts filled gaps by hiring paraeducators and substitute teachers. deBettencourt says special educators have shown remarkable resilience and found new ways to engage with students and parents. Some IEPS meetings have gotten easier to hold online for parents. Ideally, the shortages of qualified special educators will lead to much-deserved higher pay for all educators.

Joyce Epstein

Director, Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships

Joyce Epstein, a sociologist, studies school, family, and community partnerships as a component of school organization. "Students with engaged families do better," she says, so the "real" question is how all schools can use research-based approaches to engage all parents and increase student success. Epstein directs the National Network of Partnership Schools with over 500 schools and districts to address the engagement challenge. "COVID put family engagement on the front burner," she says. A new report shows that schools immediately provided meals to students and then worked to organize online classes. "The digital divide—students with and without computers—remains a monumental challenge," Epstein notes. Some "silver linings" emerged during COVID-19, including increased appreciation of educators and families for their partnership roles.

Lieny Jeon

Associate professor, Early Childhood Development

Lieny Jeon's research in early childhood development is aimed at well-being for the student, of course, but also for the educator. "Teacher well-being is key to long-term commitment to the field," Jeon says. Early childhood educators are underpaid and undervalued, but those who stick with it are highly motivated. "They love working with children," Jeon says. COVID-19 begot a lot of concern throughout the field. Jeon has chosen to use her existing educator surveys, known as the Happy Teacher Project, as a baseline indicator of job satisfaction. She has collected data throughout the pandemic to offer a before-and-after look at how COVID-19 has shaped educators' well-being. "If you don't have happy educators, you can't have happy students," she says.

Odis Johnson Jr.

Director, Center for Safe and Healthy Schools

One of the newest faculty at the School of Education, Odis Johnson says his fears about the pandemic were unfortunately realized. Serving on the board of a local school system, he understood well the scramble to make remote learning possible. The transition, however, has magnified existing inequalities. "The uncoordinated response to the pandemic did not help matters," he says. He's now focused on leading the national conversation on what a safe return to schools should look like, including an emphasis on teacher vaccinations. Noting that some systems report certain students are flourishing in the remote and hybrid learning environments, Johnson says his research will focus on measuring their success and the conditions that made it possible.

Steve Sheldon

Associate professor, Center for School, Family, and Community Partnerships

Having studied the role of family engagement in student success, Steve Sheldon was concerned from the start about the COVID-19 closures. "Man, this could be really bad," he said. He feared that families would get lost in the shuffle. Sheldon began to advise the statewide family engagement center in Connecticut about surveying teachers and families and another working throughout Maryland and Pennsylvania. In Connecticut, he helped conduct a survey of over 2,500 teachers about their pandemic experiences. Educators are doing "OK," Sheldon says, but they understand that students who need help are falling further behind. "The gap between the ones who have and the ones who need is growing," Sheldon says. "Families can help close it."

Bob Slavin

Director, Center for Research and Reform in Education

Bob Slavin was not alone in feeling "terribly concerned" about learning loss during the pandemic, and his fears "absolutely came to pass." Slavin has responded with evidence-based, proven-effective programs. His center has published comprehensive reviews of "all the different things that anybody ever tried" showing that rigorously evaluated tutoring is "overwhelmingly" the most effective tool to help students catch up, and quickly. The center will soon publish a website of the most effective programs to aid administrators to build infrastructure. "The question is how to do it at substantial scale," Slavin says, pointing to the large influx of money likely pouring into education by way of the federal COVID-19 relief package and a waiting pool of recent college graduates who will be looking for work.

David Steiner

Executive director, Institute for Education Policy

David Steiner has concerns about the potential damage caused by a slow return to in-person classes, citing Rhode Island, where schools never fully closed. "Respect the science," he says. "We can reopen with modest, sensible precautions." The return should include academic diagnostic testing, a not-always-popular suggestion. "We need to know students' current knowledge," he says. Steiner says the coming infusion of dollars to education will be wasted if not used for maximum impact. Raising teacher salaries—if accompanied by more robust entry into the profession—and adopting a rigorous high-quality curriculum are both important: "At the heart of all good teaching are what we teach and how effectively we teach it," Steiner adds.