As Johns Hopkins ramps up in-person learning and other activities for the spring semester, it is doing so with operational and safety plans developed over months by dozens of university leaders in consultation with students, faculty, and staff.

These plans are based on conversations with the university's own public health experts as well as key insights gleaned from peer institutions that successfully—and safely—conducted limited in-person instruction during the fall term. Those peers—Cornell and Duke in particular, as well as nearly 20 other universities—used a combination of routine surveillance testing, meticulously developed public health protocols, community awareness and compliance, and adaptability to navigate the fall semester with minimal transmission of COVID-19.

Though the number of new coronavirus cases remains high across the nation, Johns Hopkins leadership remains confident that its own carefully considered plans and preparations will allow for a safe return to campus for students, faculty, and staff during the spring semester.

"As public health professionals ourselves, we are of course greatly concerned about how the pandemic has continued to spread throughout Baltimore, the U.S., and the world," said Stephen Gange, professor of epidemiology, executive vice provost for academic affairs, and one of the leaders of the university's operational planning amid the coronavirus pandemic. "However, we believe the testing and additional measures that we've put into place for this spring will add to our already robust public health precautions to prepare the campus for a limited, measured expansion of on-campus activities. The experience here at JHU and at our peers has been that these measures have been effective in the campus setting so far. Because they are grounded in basic public health principles to identify and interrupt transmission, we expect that they will continue to be effective as we head into a challenging semester."

To detect COVID-19 cases and limit spread, the university has set up nine campus locations for broad-based asymptomatic and symptomatic surveillance testing—five on the Homewood campus, and one each on the East Baltimore campus, at the Peabody Institute, at the Carey Business School, and at the School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. More than 9,000 tests have been conducted over the past seven days, including more than 2,500 tests on a single day last week.

JHU's testing plans share much in common with testing protocols used at Cornell, where testing proved critical as the university resumed on-campus activity in the fall. Cornell set up eight campus sites for routine testing of students, faculty, and staff, who were asked to register and schedule their tests in advance.

And it worked. Cornell had no recorded COVID-19 classroom transmission in the fall, a testament to the effectiveness of its testing efforts combined with classroom safety measures such as masking and distancing. Overall, testing compliance among Cornell students during the fall semester was greater than 98%, and compliance among staff was greater than 95%, another factor in the school's success, said Gary Koretzky, vice provost for academic integration at Cornell University, professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, and one of the leaders of Cornell's operational planning efforts amid the pandemic.

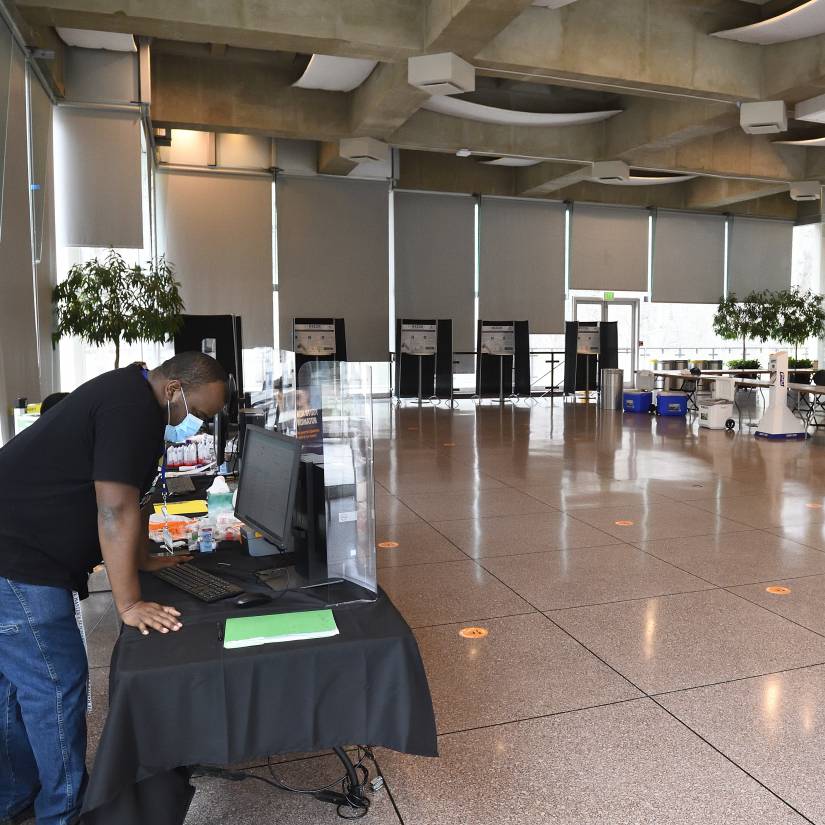

Image caption: The Glass Pavilion has been converted into a COVID-19 testing site on the university's Homewood campus

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"I think that the ease of testing combined with the fact that people actually go there to get tested—which makes people realize that we mean it—has really resulted in the community embracing it," Koretzky said.

That's not to say there weren't anxious moments at Cornell, where a few small COVID-19 clusters linked to student social gatherings prompted a critical shift in approach. School officials moved to an adaptive testing model—broadening the circle of an individual's potential contacts beyond those defined as close contacts to identify additional positive cases and limit further spread. Koretzky cited this shift, adopted early in the fall semester, as a "key factor" in the school's success.

Gange said that as on-campus activities ramp up at Hopkins, the university would monitor compliance and the effectiveness of safety measures carefully, and if necessary alter its approach—potentially increasing the frequency of testing or placing restrictions on class attendance. Plan, analyze, adapt.

"If we need to make changes," he said, "we are poised to do so rapidly."

Adaptability is a natural byproduct of the near constant conversations and evaluations being conducted by university planning committees across the country, even a year after the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the U.S. At Cornell, Koretzky said, these regular conversations—debriefs held after every identified positive case, to ask what the university might do differently or better—were an integral part of a successful approach.

So, too, did Kyle Cavanaugh, vice president of administration at Duke and one of the leaders of its COVID-19 response. He also credited robust testing, student compliance, aggressive contact tracing, and the use of single rooms for residential students with contributing to a safe and successful fall semester. Duke conducted nearly 180,000 tests from Aug. 2 through Nov. 20, identifying 241 positive cases among faculty, staff, and students, and had no incidents of classroom transmission.

"Overall I believe our faculty and students believe the semester went as well as possible," Cavanaugh said, "given the challenging set of circumstances."

With students back on campus at Hopkins and the university poised to conduct in-person instruction this week for the first time since March 2020, Johns Hopkins will no doubt face its own set of challenges. An estimated 88% of undergrads—some 5,000 students—are expected back in Baltimore as the semester begins, including nearly 1,500 in single-occupancy residence hall accommodations on the Homewood campus. Some faculty and support staff will return as well, joining the researchers and others already using campus spaces previously reopened in Phase 1.

Image caption: A hybrid virtual and in-person lecture is held at the Carey Business School

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

But even as those numbers grow, university leaders believe that their extensive preparations and protocols, paired with routine testing and a commitment from the Hopkins community to follow best public health practices, will allow for a safe expansion of on-campus activities.

"In essence our peers were running various natural experiments as they opened for the fall with combinations of the control measures we had in place and were considering," said Jon Links, professor of public health, vice provost, and JHU's chief risk and compliance officer. "So hearing their experiences informed our own decisions about control measures, including the specific design of our asymptomatic testing program.

"Ultimately, though," he added, "the decision to move into Phase 2 was based on our own assessment of conditions and operational readiness. We're ready, and we have every reason to believe we can do this safely and effectively."

Posted in Health, University News, Student Life

Tagged coronavirus, covid-19