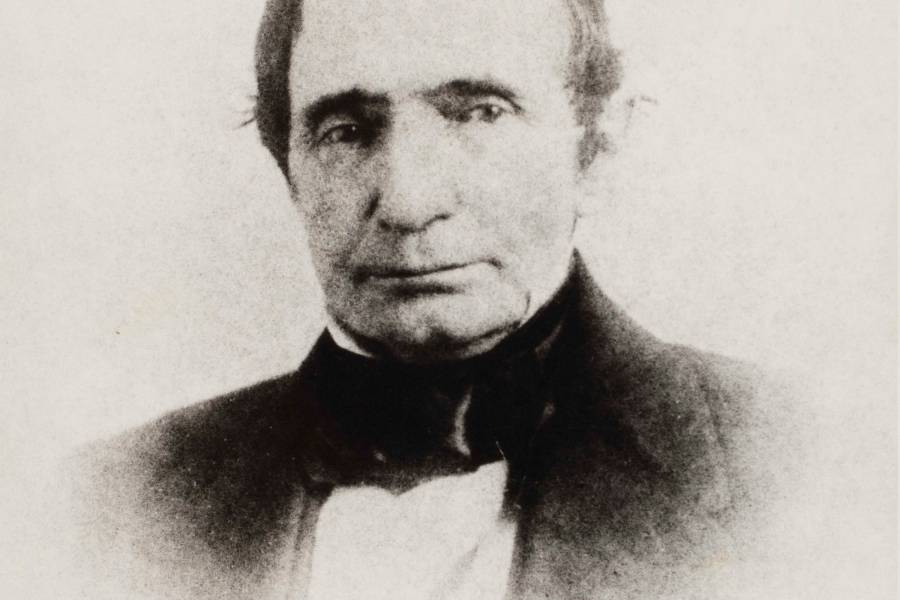

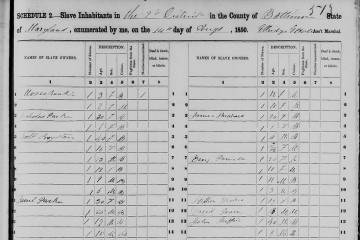

Researchers working on an initiative designed to expand understanding of the histories of Johns Hopkins University and Medicine recently discovered evidence that the institution's founder and namesake, Johns Hopkins, held enslaved people in his home during the mid-1800s.

The documents, including census records and corroborating materials, contradict previous accounts of Mr. Hopkins as an early abolitionist whose father freed the family's enslaved people in the early 1800s and "complicate the understanding we have long had of Johns Hopkins," university and hospital leaders wrote in a message to the Hopkins community today.

Though significant additional research is needed for a full understanding of Mr. Hopkins' life, these new records show that the connection of Johns Hopkins and his family to slavery was more extensive than previously known.

"The fact that Mr. Hopkins had, at any time in his life, a direct connection to slavery—a crime against humanity that tragically persisted in the state of Maryland until 1864—is a difficult revelation for us, as we know it will be for our community, at home and abroad, and most especially our Black faculty, students, staff, and alumni," wrote JHU President Ronald J. Daniels; Paul Rothman, dean of the medical faculty and CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine; and Kevin Sowers, president of the Johns Hopkins Health System and executive vice president of Johns Hopkins Medicine. "It calls to mind not only the darkest chapters in the history of our country and our city, but also the complex history of our institutions since then, and the legacies of racism and inequity we are working together to confront."

Most of Johns Hopkins' personal papers are believed to have been destroyed or lost, leaving his will and letter to hospital trustees—which include the extraordinary bequest that created America's first research university and a hospital that transformed medical education and patient care delivery—as the institution's primary, foundational reference documents. In those documents, Mr. Hopkins specifically directed that the hospital extend its care to include the indigent of Baltimore regardless of sex, age, or race, and he called upon his trustees to create an orphanage for Black children in Baltimore.

Over the past several months, JHU history professor Martha Jones, one of the nation's leading scholars of slavery, abolition, and how Black Americans have shaped the story of democracy in the U.S.; and Allison Seyler, program manager of Hopkins Retrospective, have worked to confirm the connections between newly discovered documents and the Hopkins family, examining census records, city directories, period newspapers, and other public records. The records clearly show that enslaved people were among the individuals laboring in Johns Hopkins' home in 1840 and 1850, and perhaps earlier. There are no enslaved persons listed in Johns Hopkins' household in the 1860 census.

"In many ways, there's little that is remarkable, in the context of the awful history of slavery in the United States, that a man of Johns Hopkins' wealth and status was a slaveholder," said Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History and the SNF Agora Institute. "While that doesn't surprise me, the discovery does leave me with as many questions as answers, because we know too little about, in particular, the enslaved people in Hopkins' household—who they were, what their lives were like, where and how they made their way after they were no longer enslaved. And I remain unsettled that we may not be able to know as much about them as we should want to know, and need to know, in order to tell the whole story."

Added Seyler: "For me, this discovery is about telling a more complex and nuanced story of Johns Hopkins, rather than continuing to repeat a narrative that we've been told over time."

Much of the previous narrative about Johns Hopkins' early life and his family's connections to slaveholding and abolitionism has been traced to a short book written by Johns Hopkins' grandniece, Helen Thom, and published in 1929 by the Johns Hopkins University Press. Thom's book recounts family memories to tell how Johns Hopkins' father, Samuel, as a committed Quaker, freed all of the "able-bodied" enslaved people on his Anne Arundel County plantation in 1807. Thom contends that this act of manumission imposed significant financial hardship on the family and led Johns to depart the plantation for Baltimore five years later, at age 17, and embark upon a commercial career. Thom describes Johns as "a strong abolitionist."

However, a closer examination of Thom's account, in light of recently discovered documents, reveals critical inconsistencies and raises important questions requiring further investigation.

"Many of us had been offered up what turns out to be a somewhat mythological narrative about a man who had been a Quaker and who had been an abolitionist, who had been a supporter of the Union during the Civil War. We had taken that to heart," Jones said. "What I hope is that, as a community, we have an opportunity to both express and to share with one another those feelings that this revelation may generate. And at the same time, we won't leave it there, because we still have more work to do."

Johns Hopkins plans to delve deeply into the historical record and to create a repository of related historical documents, a resource of scholarly engagement and interpretation that keeps the perspectives of the enslaved people in Johns Hopkins' household—and in Maryland and the U.S. generally—at the forefront.

"We will work together to acknowledge and account for the complex picture that is emerging of our founder, his connection to the institution of slavery, and his relationship to anti-slavery politics and post-war reconstruction," Daniels, Rothman, and Sowers wrote. "We are fully committed to continuing this research wherever it may lead and to illuminating a path that we hope will bring us closer to the truth, which is an indispensable foundation for all of our education, research and service activities."

To support this work, Johns Hopkins University and Medicine will join the peer consortium Universities Studying Slavery, and Jones will lead a group of senior JHU colleagues—including Winston Tabb, dean of the Sheridan Libraries; Chris Celenza, incoming dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences; and Jeremy Greene, director of the Institute of the History of Medicine— to propose a set of initiatives that explore the historical connections to slavery of Johns Hopkins, the Hopkins family, and other important figures associated with the institution's founding. The multi-year project will be closely linked to Hopkins Retrospective and is expected to include additional research, scholarly lectures and forums, an online archive, and commemorative events or public art in recognition and acknowledgment of the institution's history and those who were enslaved by its founder and his family.

It also will include opportunities for community participation, ideas, and input. To begin the dialogue, students, faculty, staff, alumni, and neighbors from the broader Baltimore community are invited to take part in a virtual town hall meeting on Friday, Dec. 11, from 11 a.m. to noon. Participants will have a chance to ask questions of university historians and offer input on the path forward.

"We are not alone in undertaking the difficult but essential work of reckoning with a complex history and the legacy of racial injustice," Daniels, Rothman, and Sowers wrote. "This is a solemn responsibility and an important opportunity not only to seek truth but also to build a better, more just, and more equitable future for our institution and all we serve."

Posted in University News