One team has invented a tool that could shave hours from a rhinoplasty. Another has created a sensor that ignores background noise—a device that could improve everything from telemedicine to Zoom calls.

These two Johns Hopkins University teams, a group of undergraduates and a group of graduates, are among the finalists announced today by the Collegiate Inventors Competition, an annual contest founded by the National Inventors Hall of Fame to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship at the collegiate level.

The undergraduate team, named Benegraft, has devised a tool to make it easier for surgeons to perform rhinoplasties, one of the most common surgical procedures. The team of four, all biomedical engineering students who recently graduated, heard firsthand from Johns Hopkins reconstructive surgeon Patrick Byrne how tedious and time-consuming it can be to prepare cartilage for a rhinoplasty using a traditional scalpel.

Image caption: The Benegraft team will be represented at the Collegiate Inventors Competition by recent grads (from left) Brooke Stephanian, Kirby Leo, Paarth Sharma, and Sabin Karki. Other team members include Mitsuki Ota, Millan Patel, and Marc Di Meo.

Image credit: National Inventors Hall of Fame

"We felt there needed to be a better way to do the procedure that resulted in better outcomes for the patient," said Sabin Karki, one of the team leaders.

Brooke Stephanian, another team leader added, "We saw an opportunity to simplify it."

Last year when the team showed off their idea at a convention for facial and reconstructive surgeons, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

"People wanted to know where they could buy it and we had to say not yet but we will get it to you," Stephanian said.

The team already has a provisional patent for device.

Inspired by the ease of modern kitchen appliances, the students created a multi-blade tool that's similar in spirit to a pizza cutter. Using that instead of a scalpel turns what had been a two-hour chore into a task that takes a surgeon about five minutes, they said.

Team Benegraft also includes: Paarth Sharma, Kirby Leo, Mitsuki Ota, Millan Patel, and Marc Di Meo. Their adviser is Nicholas Durr, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering.

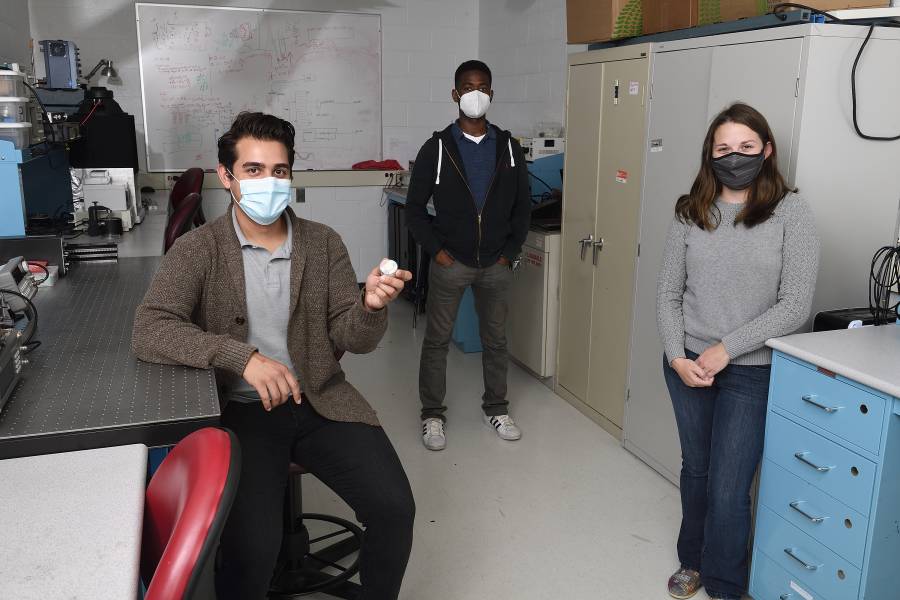

The team of graduate students is called "Hearo," a name that's a hat tip to their invention—an acoustic sensor that can detect very specific sounds within in noisy environments. The team of doctoral students leveraged the skills of Ian McLane, who'd already created an electronic stethoscope; Valerie Rennoll, who has a background in creatively using materials to minimize interference; and Adebayo Eisape, who specializes in creating objects that generate their own energy.

The sensor the team created has many possible uses. It could be part of a wearable device that would detect a patient's vital signs for remote caregiving. If placed on dolphins or whales, researchers could track their sounds and calls. It could help bands record music without having to use a high-tech studio.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The group tested the device in a number of ways, such as holding it to McLane's chest while playing loud music and holding it to Rennoll's neck while playing loud music. They heard his heart beat and her voice—and no music at all. Rennoll, who plays guitar, even affixed the sensor to the guitar while she played it with other loud music in the background. All they heard was the guitar. The team almost couldn't believe that a device this easy to build and so easily scalable for mass production worked so smoothly.

"That's one of the things about discovery," said their advisor, James West, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. "The simple things are the best."

Competition finalists will present their research and prototypes to some of the most influential invention experts in the nation—National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductees and United States Patent and Trademark Office officials. Teams will do presentations virtually this year on Oct. 28, and the winners will be announced the following day.

Johns Hopkins has had finalists in this competition 24 times, and 13 winning teams.

Posted in Science+Technology, Student Life, Alumni