In late April, headlines warned of looming meat shortages and steep price hikes in U.S. grocery stores owing to COVID-19 outbreaks in processing plants across the country. Meat industry executives sounded public alarm bells. The chairman of Tyson Foods even took out full-page ads in The New York Times and The Washington Post, claiming that America's food supply chain was essentially breaking.

In reaction, some stores placed limits on meat purchases, and where they didn't, customers applied their toilet paper–hoarding practices to chicken, pork, and beef. For a short period, a couple of dozen plants shut down, resulting in a temporary meat shortage and also the large-scale slaughter of animals. In early May, the pork industry in Minnesota alone estimated daily pig euthanizations at 10,000 to 15,000.

On April 28, President Trump signed an executive order declaring that meat processing was essential and that plants must remain open and operating. Almost overnight, the plants came back online and consumer concern abated.

The fears surrounding meat shortages might have gone away, but the less publicized consequences didn't: notably, COVID-19 outbreaks among meat production line workers. As of May, the CDC reported approximately 5,000 infections at meat processing plants, spread out over 19 states. Two independent investigations estimated infection rates in this population to be twice the national average. As of July 17, according to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, there had been 133 reported worker deaths at 43 plants in 24 states

The alarming statistics have drawn the attention of several Johns Hopkins faculty experts, who are taking steps to address the outbreak and other health concerns among this population from the angles of policy recommendation, education, and community outreach and partnership.

Poor working conditions on meat production lines are nothing new, says Ellen Silbergeld, a professor emerita in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. The author of Chickenizing Farms and Food: How Industrial Meat Production Endangers Workers, Animals, and Consumers (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), Silbergeld says that many factors play into the unsafe conditions, starting long before the pandemic hit. One major factor: sheer volume. Up to 175 chickens can be "processed" per minute under existing guidelines, resulting in, on average, 25 million killed per day in U.S. plants.

"The food production line is an adaptation of the Henry Ford car production line, meant to increase efficiencies and lower costs to consumers," she says. "But meat processing lines are fast, and companies continue to make them faster. This sets up dangerous conditions."

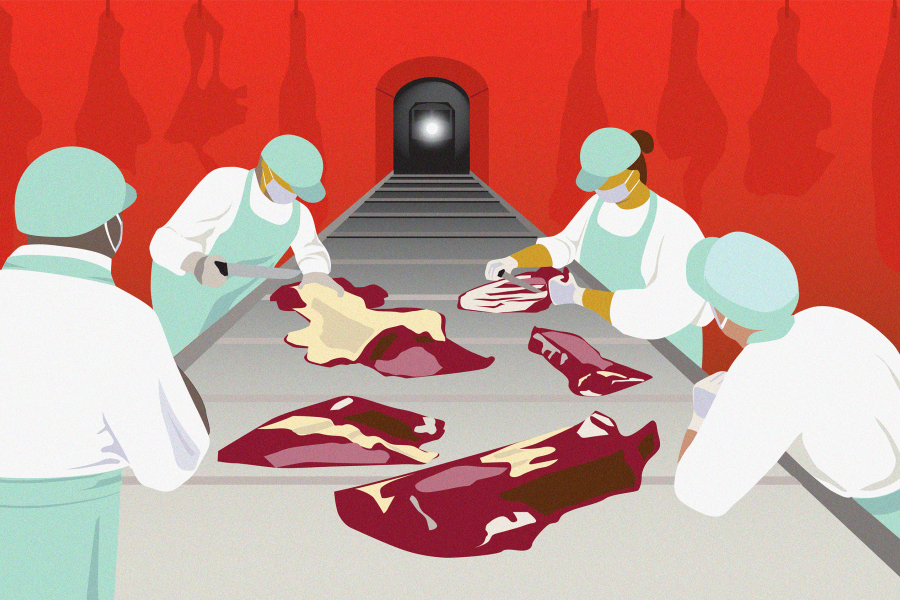

Image caption: The coronavirus pandemic has compounded the dangers to meat processing plant workers, who often have to work long shifts in close quarters

Image credit: Getty Images

A Government Accountability Office analysis of U.S. Department of Labor statistics from 2004 to 2013 revealed that when it comes to injuries and infections, workers on the lines of meat and poultry processing are at greater risk than employees in any other type of manufacturing. Silbergeld's 2014 research, published in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine, piggybacks on those findings. The coronavirus outbreak only compounds these dangers.

"This is a job where workers stand shoulder to shoulder," Silbergeld points out. "They also don't have adequate PPE—they never have."

Compounding the problem, says Silbergeld, is the scant amount of oversight from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. "There is no director, and the agency is effectively dismantled at the moment," she says. "There are no requisite guidelines for plants to follow regarding worker safety in the middle of the pandemic."

The CDC and OSHA issued joint voluntary guidelines for meat processing plants to follow, which include the standard 6-foot physical distancing and other measures. The agencies stated that they would stand behind any companies facing litigation for coronavirus exposure, as long as the companies adhered to the guidelines. In addition, the Labor Department announced it would assert authority over states in ensuring that plants remain open during the pandemic.

Silbergeld hopes to work with unions to get into plants to view some of the conditions herself. "These are workers who live in tight, crowded quarters. They aren't given access to testing. They often have no health care as part of the job," she says. "If a worker gets sick with COVID and needs to stay home, they may lose their job."

Keeve Nachman, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, says that within American society, food production workers are largely invisible. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, approximately 22% of all food production workers are noncitizens, and the occupation pays a household income below 200% of the federal poverty level of $12,760. "We have long insisted that these workers remain on the job, yet we don't support them as we do health care workers," he says. "It's a mismatch of our expectations that we'll have a healthy food supply."

Nachman recently co-authored a policy brief, along with two colleagues from his department and one from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, aimed at policymakers and employers and titled "To Safeguard the U.S. Food Supply Chain During the COVID-19 Pandemic, We Must Protect Food and Agricultural Workers." In the report, they outline steps to help protect workers, not just from meat processing plants, but food distribution facilities, farms, and anywhere along the food supply chain.

The paper outlines a four-pronged approach, which includes shield, test, trace, and treat. "We hope that by drawing on the science, we can provide recommendations that will serve as a roadmap for change," Nachman says.

Image caption: Meat shortages have caused some supermarkets to limit meat purchases

Image credit: Getty Images

The shield recommendations include advice for reconfiguring the work environment, installing physical barriers between workers where possible, and staggering arrival, departure, and break times. This may require slowing the speed of lines in order to accommodate the suggestions. "It's likely the impacts will vary by facility and animal being processed," Nachman says. "While likely not resulting in mass-scale culling of animals, it is possible that the reductions in line speeds would limit processing and result in smaller scale animal processing backlogs."

With regard to testing, the paper encourages employers to ensure frequent testing and supplemental screening like temperature checks. This leads into the tracing guidelines, which suggest that employers cooperate with local health agencies to help prevent additional spread.

The final piece of the paper—treat—aims to ensure that workers are provided with adequate health care, isolation, and quarantine pay. This includes flexible sick leave policies and ongoing monitoring.

Also see

CLF recently developed and distributed a survey, overseen by Roni Neff, which targets the workers themselves and is designed to examine commonalities and differences across the various sectors of food processing and production. Neff, program director of the center's food sustainability and public health program, sent it to 4,000 workers from across the food system on a national level. This will include food production (farming and fishing); processing (meat and dairy); distribution (trucking and warehousing); food retail; restaurants; and even food assistance programs like pantries and school meals.

"One of the things we think a lot about here is how do you make food systems more resilient to disaster," Neff says. "COVID is but one of many in our future. How do we assure the workers are protected and also protect the overall system?"

Neff hopes that by collecting information and then sharing the results with the public and people in a position to effect change, the survey will make a difference. "To the extent that we can help shift policy and employer approaches to worker safety, and meeting other needs, that's where we fit in," she explains.

"Regardless of COVID, we've been concerned for some time about the overall dependence of our food supply on the workers that make it happen," she says. "Businesses are not adequately set up to protect workers through situations like the pandemic."

History and behavioral science have shown that major behavior shifts often occur when consumers are forced out of their norm. Will a wariness about meat production, coupled with the rise of protein alternatives like the Impossible Burger, start a meatless revolution? "We look to reach those who are open to being reached," Neff says. "At a time like this, the number of people open to making a change may be increasing."

Neff's CLF colleague Becky Ramsing, a senior program officer for food communities and public health, brings another piece of worker safety improvement to the table: reducing demand for meat. "Consumers react to their food environment," she says. "Our messaging has to be relevant to them. We try to understand where consumers are and give them ideas that are easy to implement and make sense culturally."

In her day-to-day work, Ramsing focuses on a range of views to help change meat consumption habits, including its impact on health and the environment. High amounts of red and processed meat consumption, for instance, can lead to diabetes, certain types of cancers, and heart disease. On the environmental side, the industry requires considerable water and land usage—compared to plant-based foods—depleting needed resources and increasing pollutant levels. The pandemic brings on other opportunities to educate the public on the fallout of meat production, including worker health.

Ramsing advises the Meatless Monday campaign, launched in 2003, which aims to convey that a simple change can make a big difference. "Meatless Monday is one of the few consumer-facing initiatives we're involved with at CLF to help people make better decisions surrounding their food consumption," she says.

Educating people about why they should consider changes like Meatless Monday can be nuanced work, Ramsing says. "You can't just tell people too much meat is bad for them and the environment," she explains. "If you can demonstrate that people will feel better by reducing meat consumption, that's ultimately what will get them there. Sixty percent of people reduce their meat intake for health reasons, even those who are aware of the environmental impacts of meat."

The hope is that an assortment of approaches could help move the needle on food worker safety. According to the experts, the biggest barrier they all face is how to translate their messaging into action. Getting buy-in from consumers, employers, and policymakers is a tall order. While Nachman has helped push legislative change in food systems, this is his first project aimed at the health of food system workers.

"When you can tie it all into food safety, then you get Americans' attention," says Silbergeld. "This has always been the case."

Nachman hopes that by speaking to the fragility of the food supply chain, the public will care enough to make meaningful changes. "I'm most concerned about those workers who have no choice but to be on the front lines," he says. "But not everyone thinks that way. By demonstrating that the entire food chain can collapse from a breakdown along the line, people might be inclined to care."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged center for a livable future, food safety, environmental health, food production