The impeachment of President Donald Trump is playing out against a backdrop of troubling social conditions that have collided in previous eras of U.S. history to threaten the country's democratic principles, according to a Johns Hopkins University political science professor.

A new book by Robert Lieberman explores five eras when "American democracy has seemed fragile and at risk of backsliding" due to four critical threats: political polarization, racism and nativism, economic inequality, and excessive executive power.

In the book, Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy, Lieberman and co-author Suzanne Mettler of Cornell University identify the presence of those four conditions in the 1790s, in the 1850s leading up to the Civil War, in the Gilded Age, during the Great Depression, and in the 1970s during the Watergate scandal.

The book, scheduled to be published in August, demonstrates that these conditions have existed in various combinations during moments when American democracy was threatened. "What is uniquely alarming about the present," Lieberman said, "is that all four of these conditions exist in American politics today. This combination of threats is the critical backdrop to the Trump impeachment. In particular, we're witnessing the lethal combination of executive power and extreme polarization."

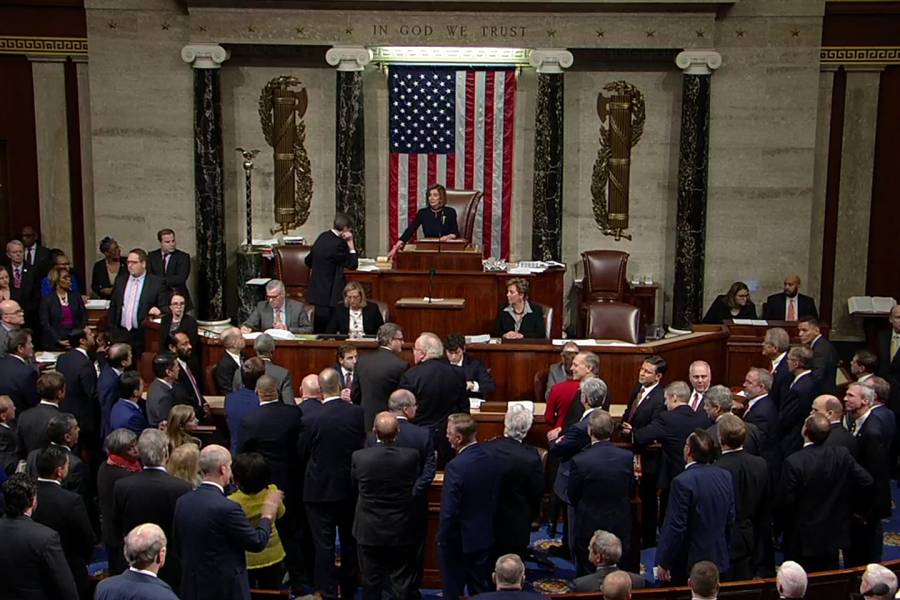

The House of Representatives on Wednesday voted almost entirely along party lines to impeach Trump on two charges: abuse of executive power and obstruction of Congress. Trump is accused of threatening to withhold military aid to Ukraine until its leader announced investigations that would benefit Trump politically by damaging a possible Democratic rival in the 2020 election, according to the impeachment articles.

Trump's administration has asserted executive privilege to refuse subpoenas that have been issued during the congressional investigation, a strategy that the impeachment articles characterized as obstruction. Republicans in Congress argue that Democrats have incorrectly elevated the facts to the level of impeachable offenses due solely to their partisan revulsion for Trump. The GOP says the Democrats have been seeking Trump's ouster since his victory over Hillary Clinton in 2016.

"Congressional Republicans have been unwilling to challenge the president and instead have used impeachment as yet another battle in the scorched-earth war against the Democrats," Lieberman said. "The result is that the checks and balances built into the constitutional structure, which are intended to prevent the excessive concentration of power in the hands of a single person or group, are breaking down in front of us. This, I fear, is dangerous for the future of the American regime."

He contrasts that extreme partisanship to the near impeachment of President Richard Nixon, who was also facing charges of abuse of power and obstruction of justice. Nixon also faced a contempt of Congress charge for asserting presidential privilege when refusing to comply with congressional subpoenas.

Nixon and his Republican allies were prepared to battle impeachment until the Supreme Court ruled that executive privilege did not protect White House audio recordings in which the president is heard conspiring to obstruct the Watergate investigation. Republican support collapsed when the transcript of the "Smoking Gun" tape was made public on Aug. 5, 1974. Nixon resigned four days later on Aug. 9, 1974.

"Watergate was bitterly partisan, but not to the extent where politics became a battle of mortal combat, as it seems to be today," Lieberman said.

Several Trump administration officials have invoked executive privilege by refusing to testify in the House impeachment investigation. Lieberman said it is possible that some Republicans could abandon Trump if the Supreme Court orders administration officials to testify. For now, though, the GOP-controlled Senate is set to clear Trump. Lieberman said it is worrisome that Republicans who do not contest the underlying facts of the impeachment case have done little to hold Trump accountable.

"There was a small number of Republicans who recognized that even though Nixon was a member of their party that he had abused his power," Lieberman said.

One of those Republican's was Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan's father, Congressman Lawrence Hogan. The elder Hogan was the only Republican member of the judiciary committee to support all three articles of impeachment against Nixon.

"That's inconceivable today," Lieberman said.

The impeachment of President Bill Clinton in 1998 was also partisan, but less so than today, Lieberman added. The House passed two articles—perjury to a federal grand jury and obstruction of justice. But two others, a second perjury count and abuse of power, were defeated even though Republicans held a majority in the House. And the GOP-controlled Senate ultimately acquitted Clinton after a 1999 trial.

What is fascinating about the political climate today is that Trump's approval ratings have barely budged since he entered office, despite the turmoil of his tenure and impeachment, Lieberman said.

That was not true for Nixon, who was very popular when he won a landslide reelection in 1972. By the time Nixon resigned in 1974, his approval ratings had tanked.

During the November 1998 election, as impeachment of Clinton was advancing, the Republican Party lost five seats in the House and gained no seats in the Senate. Typically, the opposition party gains seats in off-year elections during a president's second term.

And Clinton's popularity reached a record high during the impeachment process and remained high through the end of his second term.

For Trump, Lieberman said, "none of this had made a dent in his popularity." His support, like the nation and Congress, is "highly polarized." Therefore, it is almost impossible to gauge how voters will respond as Trump seeks a second term in the 2020 elections—other than that voters are most likely to display the nation's deep partisan divide yet again.

"It's not clear what effect impeachment will have on the election," Lieberman said. "The people who liked Trump in 2016 still support him. Those who didn't still don't."

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged politics, q+a, donald trump