Just in time for the holidays, a structure resembling a candy cane has emerged as the centerpiece of a new, colorful composite image of the Milky Way galaxy captured by a NASA camera.

The image—created with data from NASA's Goddard-IRAM Superconducting 2-Millimeter Observer, or GISMO—shows the inner part of our galaxy, which hosts the largest, densest collection of giant molecular clouds in the Milky Way. These vast, cool clouds contain enough dense gas and dust to form tens of millions of stars like the sun. The view spans a part of the sky about 1.5 degrees across, equivalent to roughly three times the apparent size of the moon.

"The galactic center is an enigmatic region with extreme conditions where velocities are higher and objects frequently collide with one another," says Johannes Staguhn, a principal research scientist at Johns Hopkins who leads the GISMO team at NASA'S Goddard Space Flight Center. "GISMO gives us the opportunity to observe microwaves with a wavelength of 2 millimeters at a large scale, combined with an angular resolution that perfectly matches the size of galactic center features we are interested in. Such detailed, large-scale observations have never been done before."

Two papers describing the image—one led by Staguhn and the other led by Richard Arendt at the University of Maryland—were recently published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The studies detail how, after spending eight hours looking at the sky and collecting data, GISMO detected the most prominent radio filament in the galactic center, making this the shortest wavelength where these curious structures have been observed. Scientists say the filaments delineate the edges of a large bubble produced by some energetic event at the galactic center.

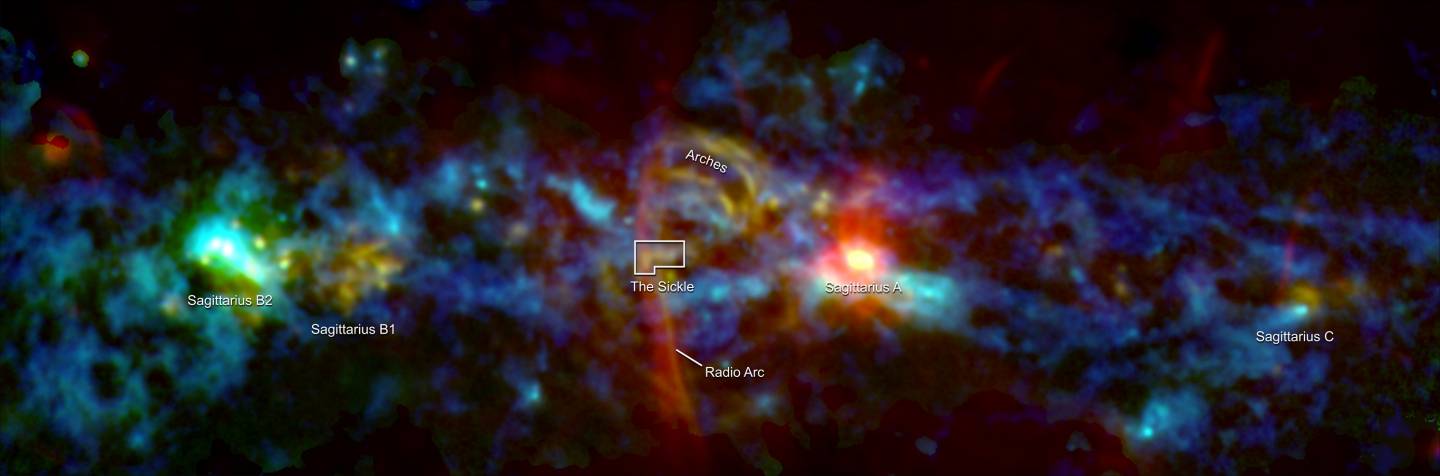

Image caption: The new image is a composite of color codes representing different types of emission sources. Microwave data mapped by GISMO is shown in green. Where star formation is in its infancy, cold dust shows blue and cyan, such as in the Sagittarius B2 molecular cloud complex. Yellow reveals more well-developed star factories, as in the Sagittarius B1 cloud. Red and orange show where high-energy electrons interact with magnetic fields, such as in the Radio Arc and Sagittarius A features. An area called The Sickle may supply the particles responsible for setting the Radio Arc aglow. Within the bright source Sagittarius A lies the Milky Way’s monster black hole.

Image credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

"We're very intrigued by the beauty of this image; it's exotic. When you look at it, you feel like you're looking at some really special forces of nature in the universe," Staguhn says.

The image is a composite of different color codes for emission mechanisms. Blue and cyan structures represent cold dust in molecular clouds where star formation is still in its infancy. Yellow features represent the presence of ionized gas and show well-developed star factories—this light comes from electrons that are slowed but not captured by gas ions, a process also known as free-free emission. Red and orange regions show areas where synchrotron emission occurs, such as in the prominent Radio Arc and Sagittarius A, the bright source at the galaxy's center that hosts its supermassive black hole. Data from GISMO is shown in green.

To make the image, the team acquired GISMO data in April and November 2012. Scientists then used archival observations from the European Space Agency's Herschel satellite to model the far-infrared glow of cold dust, which they then subtracted from the GISMO data. Next, they added, in blue, existing 850-micrometer infrared data from the SCUBA-2 instrument on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope. Finally, they added in red archival longer-wavelength 19.5-centimeter radio observations from the National Science Foundation's Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. The higher-resolution infrared and radio data were then processed to match the lower-resolution GISMO observations. GISMO was used in concert with a 30-meter radio telescope located on Pico Veleta, Spain.

Moving forward, Staguhn hopes to take GISMO to the Greenland Telescope to make large surveys on the sky looking for the first galaxies in the universe where stars formed.

"There's a good chance that a significant part of star formation that occurred during the universe's infancy is obscured and can't be detected by tools we've been using," Staguhn says, "and GISMO will be able to help detect what was previously unobservable."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged nasa, physics and astronomy