- Name

- Jill Rosen

- jrosen@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9906

- Cell phone

- 443-547-8805

Biologists at Johns Hopkins University have uncovered an important clue in the longstanding mystery of how long strands of DNA fold up to squeeze into microscopic cells, with each pair of chromosomes aligned to ensure perfect development.

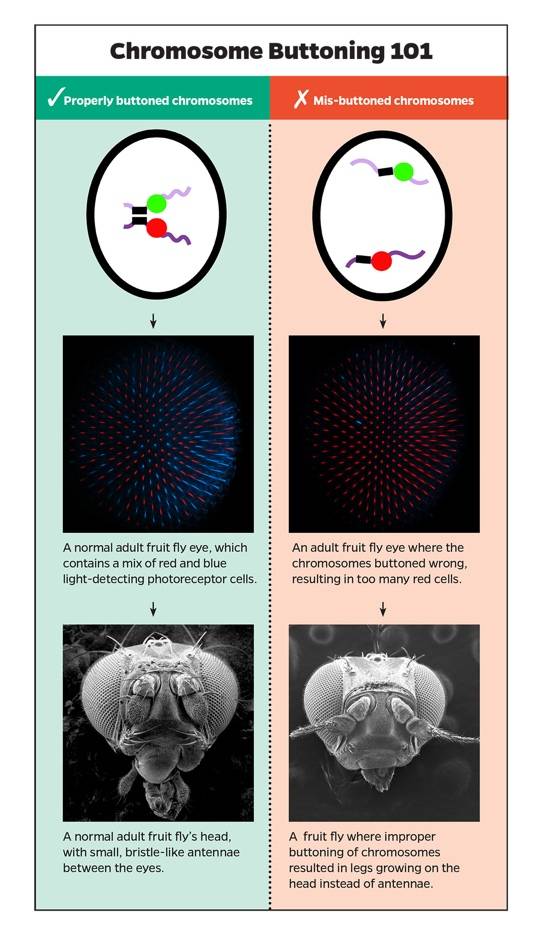

By studying flies, the researchers figured out how chromosomes meet: coming together like buttons on a shirt meeting a buttonhole. If the shirt is properly buttoned, with the right chromosomes meeting, a fly's eyes and limbs form as they should. But misbuttoned chromosomes lead to vision issues, flies with legs on their heads instead of antennae, and other defects.

The findings, published today in the journal Developmental Cell, lay the foundation for better understanding of human development. While human DNA is more complex than a fly's, chromosome buttoning happens in certain cases across species, and knowing how it works can help explain gene expression, particularly how genetic anomalies can lead to disease.

"Humans have a meter of DNA in the body that has to fold into a very compact form and do it in a similar way every time—and we have almost no idea how it works," said lead author Kayla Viets, a former graduate student in JHU's Department of Biology. "Buttoning is just one way it happens, and our work is a very important first step to a better understanding."

Image credit: Graphic by Pam Li / Johns Hopkins University

While buttoning is a specialized way that some human chromosomes come together during development, in flies, chromosomes button readily, making them an ideal model for studying the process. The team found that chromosomes in certain parts of the fly body button with greater ease than others.

The team treated the chromosomes of fruit fly larvae so that they would glow in a way that would make a proper or improper buttoning visible. In the eye, they looked specifically at the cells that allow eyes to see color, the photoreceptors, and what happened during buttoning that allowed them to develop correctly. They found that the chromosomes button easily together to correct potential issues.

But they found chromosomes in a fly's antenna worked differently, and incorrect buttoning led to striking mutations—specifically legs growing on the fly's head in place of antennae.

"Across species, chromosomes are organized in the nucleus," said senior author Bob Johnston, a developmental biologist in the Department of Biology at Johns Hopkins. "Our work adds one piece to the puzzle of understanding how DNA is folded together to make sure that genes work properly."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged biology, dna, chromosomes