In isolation cells at holding facilities for undocumented, unaccompanied youth, children are kept, sometimes for months or longer, under highly punitive conditions. Their movement is restricted, socialization minimized, and what freedom they have is limited to the boundaries of their imagination.

It was a desire to cultivate this power of expression for those who most need it that first brought poet and professor Seth Michelson to one of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement's maximum-security immigration detention centers, where he began a series of poetry workshops with the incarcerated teens.

On Friday, Michelson joined a panel of authors, historians, and activists at the Johns Hopkins Program in Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship "American Concentration Camp Teach-In." The event invited guests to think critically about the history of concentration camps and what types of facilities, historically, the term has—and has not—been applied to.

"What has happened since we moved the term 'concentration camp' into the realm of the taboo?" asked N.D.B. Connolly, who directs the RIC program. "How does the movement of that term out of everyday use make it more difficult to consider human rights violations?"

According to Michelson, the term should apply to the immigration detention centers where he held poetry workshops. Michelson soon began bringing students from his "Poetry and Politics of Immigration" class at Washington and Lee University to work with the detained teens, who ranged in age from 13 to 17.

During workshops, the young immigrants began to create their own works of art—poems that expressed their dreams and fears for the future, their memories and hardships, and their reflections on a world that brought them to where they are.

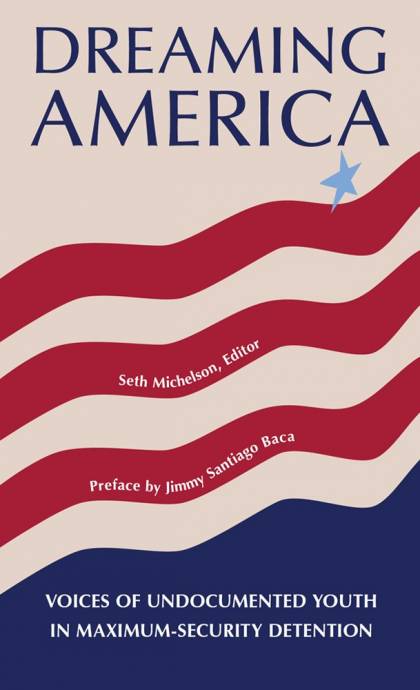

In 2017, these poems were compiled by Michelson and published in the book Dreaming America: Voices of Undocumented Youth in Maximum-Security Detention. During the event, Michelson read several of the pieces composed during the workshop, including one titled "De la tierra."

"De la tierra"

De la tierra creció una fruta,

Tan rica,

Que me puse a pensar,

¿Quién cosechó esa fruta?"From the Earth"

From the earth grew a fruit

So delicious

I paused to wonder,

Who harvested this fruit?

"Most of the authors in this book have known little of the U.S. but its carceral system," Michelson read from the introduction of his book. "In other words, they know us only at our rigid and most punishing. Nevertheless, their hope springs eternal."

To provide context for the conversation, Jonathan Katz, an author and journalist with the think tank New America, detailed a brief history of concentration camps, which, in name, date back to the late 19th century, with the Spanish Reconcentration Policy enacted during that country's occupation of Cuba.

Katz highlighted the ways in which the term "concentration camp" was accepted and embraced in the U.S. through the 1930s, with the nomenclature falling out of favor following World War II. He said it's vital to identify and acknowledge concentration camps as they appear today, even as those in power find euphemisms to hide behind.

"It's important to use the words that call on history. There's an electric current that runs through them and can shock people," Katz said. "The thing to remember is that in all of these cases, concentration camps never stop with the first group of people that are put in them, and the end results are far, far worse than what is admitted."

Following Michelson's reading, Daniel Malinsky of Sanctuary Streets Baltimore spoke about the work that organization does in Baltimore. Founded three years ago, Sanctuary Streets accompanies immigrants to court dates and other interactions with the government, as well as raises funds for bail for those who are incarcerated while awaiting hearings on their immigration status.

The event concluded with a panel discussion featuring the speakers as well as Hopkins professor Anand Pandian, professor of anthropology, and moderated by Christy Thornton, assistant professor of sociology. During the discussion, Pandian highlighted the need for people to get involved in bringing these camps to a close.

"The important thing is to act, whether it means working on the ground to get people rides like Sanctuary Streets, or if it means writing articles about concentration camps to fight rhetorically against the nomenclature of the people who are assigning these types of violence," he said. "It could mean donating money, or voting, writing blog posts, or Facebooking articles. All of it matters, and it gives us alternative modes of conceiving ways of being together."

The teach-in is the first in a yearlong series of events hosted by RIC, each organized around the theme of "Retrenchment"—the act of redefining political priorities and cutting support for military and policing apparatus.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged immigration, poetry