In Providence, Rhode Island, Johns Hopkins researchers uncovered a story of utter dysfunction: crumbling school buildings, in some cases immediately hazardous; students lagging far behind grade level, in classrooms where bullying and violence are commonplace; demoralized teachers and principals; and mazes of red tape making it impossible to fire bad actors.

The researchers' June 25 report laid bare these and other serious problems in Providence public schools, pointing to a "central, structural deficiency" at the heart of the system. The findings made national headlines, prompted a joint gubernatorial-mayoral announcement, and triggered a series of heated community forums in Providence.

Also see

"The situation was extreme," says Ashley Berner, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy. "I had never met so many dispirited students and teachers."

The institute's top-to-bottom review of Providence schools was requested by Rhode Island's governor and state education commissioner, who sought informed insights on the system's challenges.

It's not unusual for the institute, part of the Johns Hopkins School of Education, to take on this kind of advisory role with education departments, school districts, and even individual schools. In the world of education policy, the institute has established a reputation as a credible authority, known for its pragmatic, unbiased research and leadership within national conversations on education issues.

"It's incumbent upon a 21st-century School of Education to be involved in the national policy discussion in an impactful way, and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy places us squarely there, with direct access to education leaders and policymakers," says Christopher Morphew, dean of the School of Education.

The institute is currently working with more than a dozen states and 20 school districts on issues such as curriculum evaluation and design, testing, school culture, and teacher preparation. It offers counsel in the form of informal meetings, published policy briefs, reports, and more, says David Steiner, the institute's director.

"It can mean, for example, a full day in the capital of Ohio—or Tennessee, or New Mexico—meeting with senior education officials," Steiner says. "We can dig in deep on the state's current policies, providing an overview of what the strongest research says about the challenges they face."

The institute also works internationally. Berner's comparative focus led to a formal partnership with the European Association of Education Law & Policy, and Steiner and colleagues have worked to study the merits of bringing international student assessments to U.S. states.

Though only four years old, the institute's credentials run deep. Steiner has carved a lengthy career in education from both the academic and policy angles, and he served as New York state commissioner of education from 2009 to 2011.

Image caption: David Steiner, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy

"There's a certain basic comfort level among state leaders working with our institute, because I sat where they sit," Steiner says. "They know I've seen the world from their perspectives, and I know the pressures and circumstances."

Steiner, also the former dean at the Hunter College School of Education, joined Johns Hopkins in 2015. Berner had worked with Steiner as deputy director of a similar education institute at CUNY. The two experts expanded upon their work and have assembled a rapidly expanding team.

"What's unique about our work is, first of all, we sit at a world-class university—there aren't a lot of policy think tanks within universities," Berner says. "We're also not politically aligned, which means our guidance is trusted across the political spectrum. If one of our partners doesn't get the news they want to hear from our research, we're still going to give it to them."

Beyond its policy work, the institute is currently developing a series of innovative tools to support individual schools and school systems.

Image caption: Ashley Berner, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy

One is the Knowledge Map, which guides school systems through wholesale inventories of their English language arts, or ELA, curriculum, to identify which content areas are lacking. The underlying goal is to help bridge achievement gaps between students of different backgrounds, by encouraging a common body of critical knowledge.

A request from the Louisiana superintendent of education led to the birth of the Knowledge Map, and its results influenced the state's approach to secondary ELA. In Baltimore, the resource led to adoption of a new high-quality K-8 curriculum called Wit & Wisdom and a redesign of high school materials.

"Our work in Baltimore is extremely important to us," Steiner notes. "We believe we should be very, very involved in supporting the city in its ongoing work to improve."

The institute has recently used the Knowledge Map in eight districts in Massachusetts and several large urban districts elsewhere.

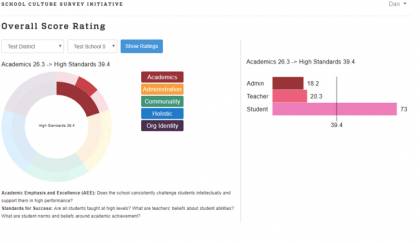

Image caption: A sample data snapshot from the School Culture Survey, which can produce layered, personalized reports based on feedback from students, teachers, and administrators, giving schools a realistic look at their values and identity.

Another resource called the School Culture Survey, currently in field tests, looks for research-based indicators of strong academic and civic outcomes. It provides a visual, online tool to help schools gauge how their missions and expectations align with actual practices.

Both the Knowledge Map and the new survey provide both immediate data for leaders and also long-term research possibilities for the institute.

This month, though, the team's dominant focus is the Rhode Island report, as they watch the impact on the state's education leaders.

"We're hoping the report can lead to real change," Berner says. "It's quite rewarding when our work is cited widely, and to see policymakers picking up the conversation."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged education, education reform, institute for education policy