The Hopkins Symphony Orchestra's Concert Orchestra dives into the 1700s for its final performance of the season this weekend with a program exploring the breadth of the classical era. The concert takes place at 3 p.m. Sunday in the Bunting Meyerhoff Interfaith and Community Service Center, and is free and open to the public.

The program includes:

- Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Symphony, op. 11, no. 1, the first movement

- Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Symphony in F Major, Wq. 183/3

- Franz Joseph Haydn: Cello Concerto in C Major, the first movement

- Isabel Won, cello, HSO Concerto Competition runner-up

- Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony no. 83, The Hen

The Hub caught up with Jordan Randall Smith, the HSO's assistant conductor and HCO conductor, to talk about the classical era, how the concert pieces inform and influence one another, and how musicians are thinking about reassessing the classical canon.

Tell me a little bit about this program, because it's kind of a straight-up classical period.

The germ of the idea for this concert came out of the runners-up for the concerto competition. Gabriela Nisly performed the [Franz] Doppler piece back in fall, and Isabel Won played the Haydn Cello Concerto in C Major. So we're doing the first movement of that, and it started as a jumping-off point for everything else. Once you get back to the pre-Romantic era, my philosophy is that sometimes it's kind of nice to give people a chance to hear the subtle differences between pieces of that period. So what about a Haydn symphony to go with the cello concerto?

We're doing The Hen symphony, and the two pieces are set apart by 20 years. And, to me, it's easy to look back to the 1700s and think 20 years is nothing, but, just as a point of reference, you might've seen a few stories in pop music recently talking about how TLC's "No Scrubs" just turned 20 years old. So I think about that in terms of thinking about how much can change in musical taste and style over the course of 20 years, and I think it was no different then.

That's true; we're casually more aware of how much music changes during our lives, but we don't always apply the same awareness to music of the past.

And there's really a radical shift between the elegant kind of pastel colors that come up in the cello concerto and then you get to The Hen—the name refers to this clucking sound that comes in as a sort of second theme of the opening movement—but the main theme is extremely sturm und drang and very angsty. I was telling the orchestra, "This is where Haydn goes emo a little bit," and reminded them that this is the music that inspired Beethoven to take it to the next level. At some point, Beethoven was hearing this piece or something like it and thinking, This is where I need to be going.

Typically when you hear people talk about the classical period, it's Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven in that order. Well, Mozart was born more than a generation after Haydn and died before Haydn, so Haydn was writing long before him and well after him. And with that context in mind, The Hen is pretty advanced and powerful music.

How do the C.P.E. Bach and Bologne fit into this program for you?

They kind of fork off of Haydn in different ways. C.P.E. is, of course, Johann Sebastian Bach's son, his fifth, and probably his most prolific composer son. Mozart said, "Bach is the father, we are the children," but he was talking about C.P.E.

C.P.E. also wrote the watershed treatise on keyboard playing of his generation, and nobody had written anything quite like his book. We still use it today to figure out how to do trills correctly and to know what people were doing back then. So C.P.E. was one of the big thinkers of the time that composers like Haydn would've been attuned to.

Now, when C.P.E. was writing symphonies, the word symphony didn't mean what we think of it now. There's not quite as much structure or attention to key areas and the relationship between them. What I love about C.P.E., and the way I think about it, is that he's kind of writing in the wild west when it comes to symphonies. His symphonies are all over the map. We'll have the harpsichord part in our version because the kind of crunchy, rhythmic quality was a sound of the time. Harpsichord provided some rhythm and texture within the string sound.

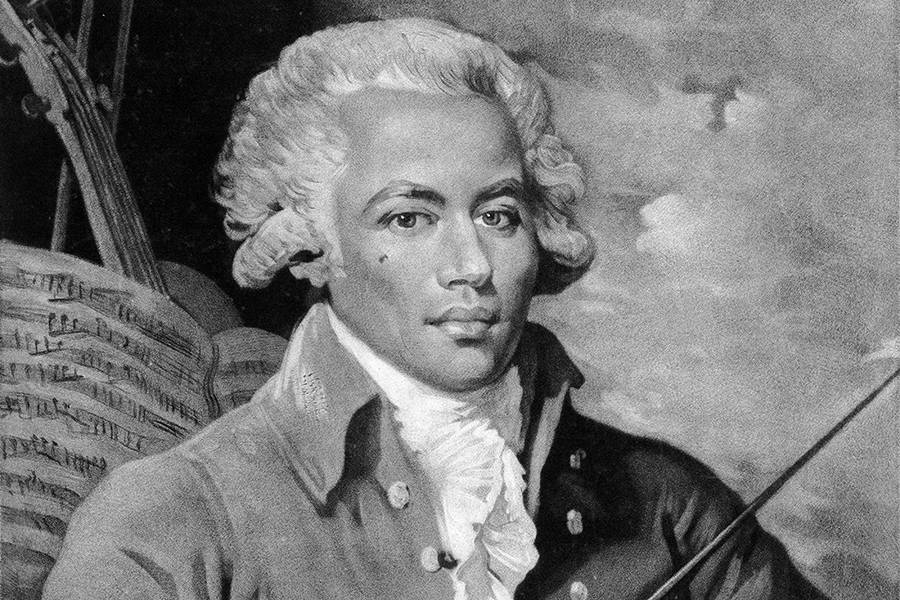

And the other composer is Joseph Bologne. He was born in Guadeloupe and eventually moved to Paris because his father was a colonel of some means. Now, The Hen symphony is one of Haydn's Paris symphonies, which were commissioned by the Loge Olympique orchestra. The conductor of that orchestra was also a composer, Joseph Bologne, and his formal title was Chevalier de Saint-Georges. In fact, on the scores it doesn't even say his name, just the title.

He wrote a lot of interesting music, and we're doing the first movement of Symphony, op. 11, no. 1, and this is an earlier idea of what a symphony is, and this is French classical, which we really don't hear a lot of. When we think of classical era music, we tend to think of Viennese classical, Mozart, Haydn, and early Beethoven. And this is not that. It has a different kind of sound.

I appreciate seeing the Bologne on this program—the biracial son of an aristocratic French plantation owner who was a fencing champion, a colonel of an all-black, pro-Revolution French military regiment, and became an accomplished violinist, conductor, and composer. I know you're an advocate for diversifying and updating the canon, and I think when classical music—or art in general—talks about diversity, the emphasis tends to be on the present. But we can also open up what we know and understand of the history of art by recognizing artists otherwise overlooked. And Bologne, because he isn't exactly unknown, is a subtle reminder that access to opportunities—his class laid a foundation for his talent to grow—matters.

And it's kind of a self-perpetuating sort of thing. The model for the classical canon is that the cream will rise to the top. We're like, I want the best stuff, put it through the ringer for a couple of hundred years and then call me. I think it was Eastman, two summers ago, who made me think, Man, I have some deprogramming of my brain to do. When I heard his radical sounds I thought, There is really interesting music out there that I don't have any purchase on.

So I realized I need to go back and start to look at a lot of music that no one in school ever told me I was supposed to look at—to start over and reconsider how I looked at things. My personal journey has led me to think, yes, if you throw at me an obscure European white dude composer from 200 years ago, if I've never heard of him maybe there is a good reason. But if I haven't heard of a composer and there's any evidence that maybe the reason I hadn't wasn't the quality of the work—maybe it was gender or any number of other things—then maybe it needs to have many more looks from people today.

Posted in Arts+Culture