Many astronomy researchers have benefitted from sky surveys containing millions of stars and galaxies observed by telescopes around the world. But Brice Ménard's colleagues say his imagination and insight make him particularly adept at discovering the universal secrets hidden in a daunting amount of data.

On Tuesday afternoon, Ménard, an associate professor in Johns Hopkins University's Department of Physics and Astronomy, received the $250,000 President's Frontier Award to support his exploration of new ways to analyze astronomical data. He said it was unexpected to see university President Ronald J. Daniels, Provost Sunil Kumar, Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Dean Beverly Wendland, and other colleagues walk into the classroom where he was teaching to surprise him with the news.

The award was established by chair elect of the Johns Hopkins University board of trustees and alumnus Louis J. Forster and alumna Kathleen M. Pike to recognize one faculty member each year for five years and "to give them freedom and allow them to do extraordinary things," Daniels said to Ménard at the presentation.

Image caption: From left: JHU President Ronald J. Daniels, Brice Ménard, Dean Beverly Wendland, Provost Sunil Kumar, and Timothy Heckman during the presentation of the 2019 Frontier Award

Image credit: Will Kirk / Homewood Photography

"But the key is, of course, the person that receives it must him- or herself be extraordinary," Daniels said, "and clearly that is the case. … Colleagues outside your discipline who reviewed the nomination had very little difficulty in seeing what a worthy candidate you would be."

Timothy Heckman, chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the Krieger School, noted in his nomination letter that Ménard has worked with very large astronomical data sets that have been available to hundreds of other very capable scientists, often for many years.

"His genius," Heckman said, "was to conceive of and develop new and potentially far-reaching ways to analyze these data. He then used his intellect and intuition to make a series of remarkable and often unexpected discoveries."

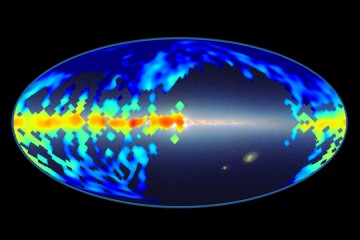

Ménard used the data set of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey to discover that tiny grains of cosmic dust, formerly only known to exist inside galaxies, are distributed throughout the universe. This insight had major implications for understanding the chemical evolution of the universe, Heckman said.

Image caption: Brice Ménard

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Ménard also developed a new technique for determining distances in the universe. As he explained in 2014, when he received the David and Lucile Packard Foundation Fellowship for Science and Engineering, his approach does not rely on the colors of light, as previous methods did. Instead, it extracts information from specific patterns in the way galaxies tend to group with each other, due to gravity.

"Knowing how far away an object in the sky is located is important," he said, "because looking far away is seeing back in time, and observing galaxies at different distances allows scientists to study how the universe evolves with time."

Recently, Heckman said, Ménard has been developing a new tool based on the principles of statistical physics that can ingest very long lists of objects with attributes and automatically sort them in a way that reveals deep underlying patterns and order.

Known as the "Sequencer," it has been successful as a prototype and has the potential to yield significant breakthroughs in astronomy and other scientific fields, as well as in public health, business, and engineering.

"I spend most of my time studying the universe, millions of stars and millions of galaxies," Ménard said at the celebration. "The challenge is out of all these data to try to extract information, signals that we have not seen, to always push the limits of knowledge."

He added: "Most of the time I don't know what I am going to be excited about. My approach typically is to look at these very large data sets to explore them and on the way, unintentionally, I sometimes stumble upon interesting things, unexpected things, and that is how the whole scientific research process starts."

Ménard began his studies in Paris and then earned his PhD working at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany and the Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris. He was a postdoctoral member at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and a senior research associate at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics in Toronto. In addition to being on the faculty at Johns Hopkins, he is a joint member of the Kavli Institute for Physics and Mathematics at the University of Tokyo.

Ménard received the 2011 Henri Chrétien grant, awarded by the American Astronomical Society; was named the 2012 Outstanding Young Scientist of Maryland; and received a 2012 Sloan Research Fellowship.

Beth McGinty, an associate professor of health policy and management at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, was recognized among the finalists this year. She will receive a presidential monetary gift of $50,000 to support her academic work, which focuses on developing communication strategies to reduce stigma surrounding mental illness and substance use disorders and to increase support for policies that assist individuals facing those issues.

Previous recipients of the President's Frontier Award are:

- Sharon Gerecht, a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering

- Scott Bailey, an associate professor in the Bloomberg School of Public Health's Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Michael Hersch, chair of the Composition Department at the Peabody Institute

- Deidra Crews, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology

"It's an amazing opportunity to expand in new directions without having to apply for grant funding," Ménard said. "It's freedom of research, freedom of exploration. It's the ability to try very risky ideas. ... As far as I know, there are not many universities providing an individual with so much in resources."