When the Armistice was announced ending World War I on Nov. 11, 1918, Elisabeth Gilman, a Baltimore woman with close ties to Johns Hopkins University, found herself among the thousands of French citizens whose joy overflowed in a wild outburst of celebration in Paris.

Gilman was the youngest daughter of Daniel Coit Gilman, founding president of Johns Hopkins University. Her family had been at the center of Baltimore society and its intellectual community, but at age 49, she had become restless and welcomed a chance to step out on a new path.

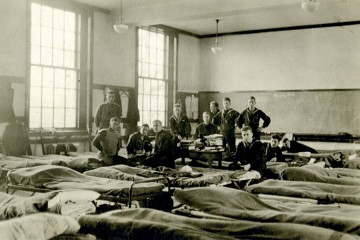

Gilman volunteered to go to France to support American troops shortly after the U.S. entered the Great War in the spring of 1917. She managed a YMCA canteen for soldiers at a rest and recreation hotel in Paris.

It was quite a change from her life in Baltimore.

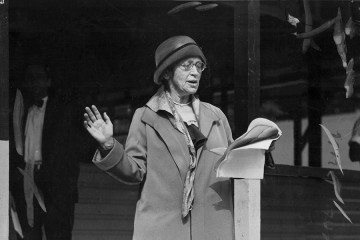

Image caption: At a point in life when most women of her station would have quietly withdrawn to private pursuits, Gilman was just getting started

Image credit: Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

During her travels, she was a faithful correspondent, writing several times a week to her older sister, Alice, and her favorite aunt, Louisa.

She wrote to Alice on Nov. 12, 1918, describing "the great and almost mad joy of the Armistice."

She visited the Place de la Concorde, where a landmark statue that had been covered in black crepe throughout the war would be unveiled. She described seeing "the Strassbourg with her crown of gold."

She wrote:

The crowds were enormous & on returning it took about 30 minutes to go two squares.

That night, when an opera singer sang the "Marseillaise" from the balcony of the Matin [newspaper office building], it was hardly safe to be afoot for people were so crushed by the crowd. But I made it home safe.

A week later she wrote again to Alice:

Life is so very strenuous in these days that I hardly know which way to turn. The boys are flocking to Paris. It is almost impossible to keep up but we do the best we can.

Paris, as I wrote to you, went wild with joy and has not yet quite recovered. I am too anxious for the future, with the Kaiser at large now and an unstable government in Berlin, to be exuberant but I am thankful not to have any more men killed.

There is a restless spirit in the air, but things will go alright, I imagine.

Elisabeth remained in France, providing services to demobilizing troops, until 1919. When she returned to Baltimore, she became the most prominent social activist of her day, leading all sorts of causes aimed at improving the lives of the city's working-class men, women, and children.

In 1930 she was a candidate for governor on the Socialist Party ticket. Almost every year thereafter until she died in 1950, she was the Socialist's choice to run for one office or another. She never won but she used her platform to broadcast her ideas for social reform.

Ross Jones retired as Vice President and Secretary of Johns Hopkins University in 2003. His biography, Elisabeth Gilman: Crusader for Justice, was published last month.

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged history, johns hopkins history