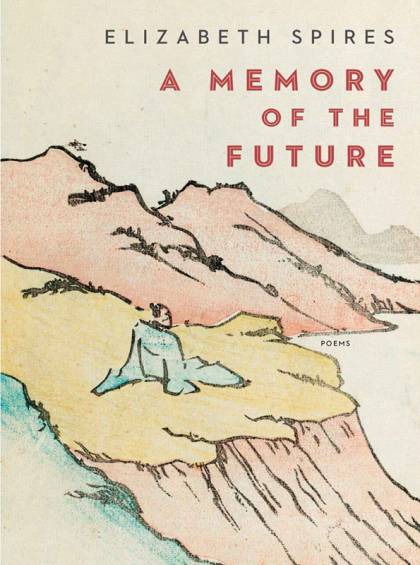

In her newest poetry collection, A Memory of the Future (W.W. Norton & Company), Johns Hopkins alum Elizabeth Spires moves through recollections and ideas. In advance of her upcoming reading at the Ivy Bookshop this week, the Hub caught up with Spires, a professor of English and Chair for Distinguished Achievement at Goucher College, to talk about her collection's relationship to the poet Elizabeth Bishop, the emotional leaps poetry can make, and time travel.

Image caption: Elizabeth Spires

Image credit: Celia Dovell Bell

I'm going to think I'm being clever here and ask you a question similar to one you asked poet W.D. Snodgrass when you interviewed him for The American Poetry review in 1986, when you said you looked up the root word of his surname in the Oxford English Dictionary. The OED defines "spire" a few different ways, some less common now than others: One of the series of complete convolutions forming a coil or spiral; a stalk or stem of a plant, especially one of a tall and slender growth; spar or pole of timber. Do you think your name has any relationship to your writing?

I feel lucky in my naming. Life is sometimes mysterious with signs and symbols (and names) taking on a resonance, or having a metaphorical meaning, that goes beyond the literal. I guess I do sometimes see my poems reaching—a bit like a spire—upward. (Although you could say there is also a downward motion, into the earth, in A Memory of the Future.) And spirals and circles fascinate me. I grew up in the small town of Circleville, Ohio (really and truly!) although until I left at eighteen I never thought that was an odd name for a town to have.

I also wanted to ask you a pair of questions you asked Elizabeth Bishop when you interviewed her for the Paris Review in 1981: Have you ever had any poems that were gifts? Poems that seemed to write themselves?

Only two poems ever wrote themselves (meaning the first draft was about 98% there). Both were included in my first book Globe: a dramatic monologue titled "Exhumation" and the poem "Tequila." I have no idea how or why it happened with those two poems. I wish there had been more, that I could occasionally write that easily and freely.

I ask the two above questions because I'm curious: did meeting with and talking about poetry with two poets that I believe you admire influence or inform your own poetry, thoughts about the writing process, or approach to the writing life at all?

I was drawn to Elizabeth Bishop's work before I ever met her. At the time I didn't quite grasp what she was doing. Her poems seemed both straightforward and descriptive and, at the same time, mysterious—like something crucial was being withheld. Bishop was one of the very few poets that I ever wanted to meet. Normally, I believe that reading a poet's poems is enough. You don't need to meet the writer in the flesh. And some of the "greats" would be terrifying to meet—Emily Dickinson and Gerard Manley Hopkins come to mind, because their intensity would be frightening.

But I wanted to meet Bishop because I think I was looking for a model, an older woman writing poems in the same time that I was living in. Her poems will never be tarnished for me by what I know about her all-too-human life. In fact, it inspires me to think that amazing poems, immortal poems, are written by flawed human beings.

Certain poems of W.D. Snodgrass were touchstones for me, like "Old Apple Trees," "After Experience," and several of his poems on paintings. I wanted to interview De (who was a friend) because he was the first one to write confessional poems—in Heart's Needle—not Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, or Sylvia Plath. In fact, Snodgrass influenced Lowell, who was his teacher at Iowa, not the other way around. It seemed important to set the record straight and give Snodgrass the credit he deserved.

Also, in both of those interviews, you get from introductory small talk to pretty deep topics, themes, and discussions pretty quickly. Similarly, in the poetry collections of yours I've read—I'm mostly familiar with Worldling, Now the Green Blade Rises, The Wave-Maker, and the new A Memory of the Future—you also start in the here and now and seamlessly move right into life's deep ends pretty quickly. I mean, "Riddle," from your new collection, opens with:

Puffed like an adder.

Deflated like a balloon.

Tiny or huge, you are

Never the right size.

Two deceptively simple visual ideas run right into the anxiety of taking up space in the real world. For you, what makes poetry—and poets—so comfortable with, and capable of, these rather big emotional and intellectual leaps?

There's probably no point in writing or reading poetry if you don't want to take leaps. Poems may begin in a seemingly "ordinary" moment, but poems find something in that small, ordinary moment that are "big." It may be obvious to say, but it's a totally unexpected way of seeing or experiencing something that takes you a little bit out of yourself, that gives you an insight you wouldn't have had otherwise. You can't will it or control it. It just comes when you're least expecting it. It could be likened to a (rare) moment of grace.

For me, an awareness of and sensitivity to time's passing seems to run through Memory, and I seem to recall hints of that in Worldling and Wave-Maker, as well as when alluding to your mother's passing in Now the Green Blade Rises. Now, I don't want to ask why that subject interests you—I mean, on some level it's the inevitable subject that takes place between the book covers of birth and death—but to ask how your relationship to and understanding of time's passing has changed over time.

I wish I understood what time is. I don't! (The poet James Merrill described it as "Ever that Everest among concepts.") One's sense of time, of time passing, certainly changes as one gets older. More and more, I feel the press of time. One of my favorite poets, A.R. Ammons, said poetry really only has one subject: CHANGE. To state the obvious, things couldn't change, we couldn't change, if time didn't pass. Time is the element we swim in.

I believe all sorts of things about time: that we are time travellers (when we remember the past or anticipate the future); that the past, present, and future probably co-exist (meaning it's not a straightforward linear progression); that time can mysteriously speed up or slow down at certain moments of joy, pain, or terror; and that full immersion in writing a poem (e.g., the flow state) takes us out of time for a little while.

I detect a consideration of how time's passing informs how we choose to put things in the title poem, "A Memory of the Future," when you start off: "I will say tree, not pine tree,/ I will say flower, not forsythia."—suggesting, to me, that there's an intentionality to the words we choose to call things, and the reasons behind those intentions may change with age.

The poem that you quote came out of reading The Zen of Creativity by John Daido Loori. He writes: "One of the beautiful aspects of Asian poetry is the vagueness of its languages." I had never thought about the beauty of vagueness. Poetry workshops teach poets to be specific, to strive for accuracy and precision. But what if there are poems to be written in English (there are, of course!) that are successfully "vague" or general? I have not given up on specificity, but I am interested in exploring this further. The question is, what kind of dramatic situation or experience lends itself to intentional vagueness? In the poem "A Memory of the Future," the speaker is moving into old age, a place of loss and unremembering. Certain specific words are no longer available; they cannot be located by the speaker. There are only larger categories, "tree, not pine tree" "flower, not forsythia."

Where has A Memory of the Future taken you and your work? Does finishing a book point you toward a how and what that the next growth of writing/poetry might explore?

The poems in A Memory of the Future were written over the past ten or twelve years. I feel (or maybe I should say hope) there is one more chapter left in my life and writing. I am as interested as ever in exploring the "big questions," questions that don't have answers, but this exploration will have to be triggered by actual life events, often encountered by chance, not by willed philosophical musings. I am not so interested any more in writing poems that are explicitly autobiographical. I'm thinking more about the core self that is masked by ego and persona. Looking at the 8 or 10 new poems that I have, I see them that some of them (not all) are preoccupied with endings, with death. I want to keep changing and evolving, rather than writing the same poem over and over. I hope the poems in my future surprise me.

Elizabeth Spires reads at the Ivy Bookshop Friday, September 7 with Michael Collier at 7 p.m.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion